Eight-year-old Ajit Kaur picks up the chakra with confident hands and begins to spin it.

The motion transforms the loose web of heavy, weighted rope attached to the frisbee-sized circle of metal into a rapidly rotating canopy whirling rapidly over her head.

At full extension, the chakra is more than two metres across.

Standing in the shadow of the flying strands with a look of calm concentration, Ajit moves the chakra gracefully from hand to hand, high then low, keeping it moving all the time.

She even hands it off, while still in motion, to another student, who does equally acrobatic moves before handing it back.

It’s a typical Tuesday night practice at Newton’s Beaver Creek Elementary school for Ajit and 20 other young apprentices in the centuries-old Sikh martial art of gatka.

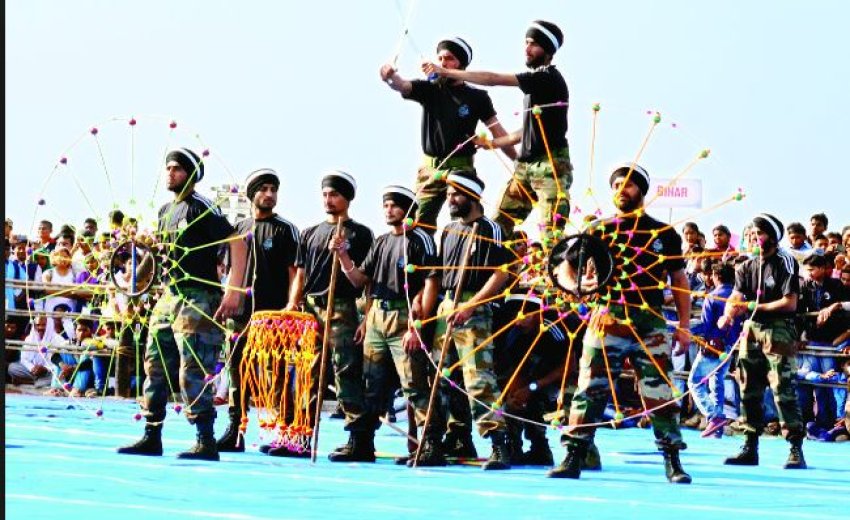

Parents stand on the sidelines or sit in the bleachers watching head coach Mahabir Singh and head instructor Gurdit Singh put their sons and daughters through their paces.

Like everyone involved in the program, the coach and instructor are volunteers. Parents chip in for the equipment and other costs.

The original version of the chakra rotating above Ajit’s head was a flat steel ring that was lethal up to 50 metres in experienced hands. (An altered version of it rode on the hip of actress Lucy Lawless when she starred in the television series “Xena, Warrior Princess”).

Like the other weapons in the Gatka arsenal – swords, bows and arrows, spears, axes and daggers – the chakra has evolved to become something less deadly and more ceremonial.

This evening, most of the students from Surrey’s Akal Academy are wearing traditional loose-fitting tops and bottoms, many with the turbans, kara (metal bracelet) and kirpan (small ceremonial dagger) that identify them as Sikhs.

They range in age from eight to 16 (the allowable age range for beginning gatka students is six to 25).

They are here to learn the various weapons and fighting styles that are part of a martial arts tradition of self-defence that developed after the fifth Sikh Guru Arjan Dev died in 1606, tortured to death in prison by soldiers of the Mughal empire.

It’s not clear exactly why the guru drew the wrath of the Islamic imperial power that controlled most of the Indian subcontinent for three centuries. Some historians say the Mughal ruler of the day ordered the guru’s death because he was threatened by the rising popularity of the Sikh faith, while others suggest the ruler was unhappy with the guru because he supported a rebel prince.

Whatever led to it, the death of the fifth guru was an action with far-reaching consequences, both for the Sikhs and the Mughal empire.

The son of the murdered fifth guru became the sixth, Guru Har Gobind, who taught a doctrine of self-protection that included training in martial arts and combat for both men and women.

The result was an intensely practical martial art, designed to be easily learned, to include all available weapons and permit a small group of fighters to defeat a much larger force.

The “warrior saints” as they called themselves, were taught to fight with both hands (two swords, a sword and a shield, twin wooden quarterstaffs or any other combination) to constantly move in a circular direction to cover blind spots, attack without hesitation and strike hard.

Gatka is usually taken to refer to the practice stick used by novices, but a number of sources claim it is also a combination of two words, the first one meaning grace or liberation while the second means one who belongs or is part of a group.

Thus, gatka is said to mean “one whose freedom belongs to grace.”

By the time of the 10th guru, Gobind Singh, Sikh fighters had developed a formidable reputation.

The guru himself was a skilled archer, horseman and experienced warrior known for wielding two swords at once.

He was at the head of a small group of Sikh warriors who took on a much larger force of Mughal soldiers at the legendary battle of Chamkaur in 1704.

One account of the combat at the time said a small fort used by 40 Sikhs was surrounded by 700 cavalry equipped with artillery. Other versions of events place the number of Mughal opponents much higher.

While only a handful of Sikhs, including the guru, survived Chamkaur, they inflicted massive casualties and the battle is considered a turning point that led to the eventual defeat of the Mughal force.

Centuries later, the distant descendants of the men and women who fought those battles continue their tradition on a hardwood floor with basketball markings.

On this dark winter evening, the boys and girls chatter and laugh as they take a break from practice.

“My mom made me come,” one student tells a visitor. “But I like it now.”

One three-year-old boy, too young for the program, nevertheless shows up impeccably dressed in a tiny turban and miniature sash, courtesy of his grandmother.

A family friend explains the child was making a fuss because his older brother got to go to gatka and he didn’t.

Determined to keep up, the little one chugs along behind the bigger students as they run laps.

Practice resumes and students pick out bamboo swords from an array of training weapons arranged on a cloth on the centre of the gym floor.

The youngsters spar, circling and staying alert to threats from all sides.

Parent Avtar Singh Gill watches his eight-year-old son Mehtaab Singh practice swordplay against a fellow student who is a full head taller than Mehtaab.

The two boys begin slowly, the sound of bamboo against bamboo accelerating to become a near-continuous staccato clacking.

They are reconnecting with their roots, getting hands-on history.

“It’s more than a game,” Gill says.

It’s also about learning discipline, and developing the attitude of humility that is part of the martial arts tradition.

Gill says watching his son has reawakened his own interest in the tradition, and he’s thinking about finding an adult gatka program.

Elsewhere in the gym, another boy struggles to keep two practice sticks rotating in both hands. It’s not as easy as it looks.

As the session draws to a close, coach Mahabir Singh puts on a demonstration with the assistance of instructor Gurdit Singh.

When the grey-bearded gatka master moves his practice sword, it cuts the air with an slicing whoosh that can be heard at the other end of the basketball court.

From opposite corners, the two men advance on each other quickly, leaping high the way their ancestors would have to ensure a single, deadly stroke.

Their wooden sword blades make raucous contact.

For that moment, gatka is anything but kid stuff.

For more information about gatka, contact [email protected] or phone 604-780-7200.