Respecting the rights of the religious and non-religious alike means setting consistent rules.

One of the most difficult balancing acts in democratic societies involves simultaneously upholding freedom of religion and freedom from religion.

One of the most difficult balancing acts in democratic societies involves simultaneously upholding freedom of religion and freedom from religion.

In recent years, religious debates have abounded, focusing on crucifixes in courtrooms and schools, Sikh turbans in the workplace, Jewish mezuzahs on condominium doors, and the wearing of religious headscarves like the Islamic hijab. In some places, fish-shaped signs with slogans like “Jesus Saves” have found homes on trees and sign poles in public places.

To this day, memorial crucifixes on roadways mark places where loved ones have died, and the Bible is still the official book upon which oaths are taken. Some schools – including universities – are under scrutiny for requiring faculty members to adhere to faith-based declarations as a condition of employment.

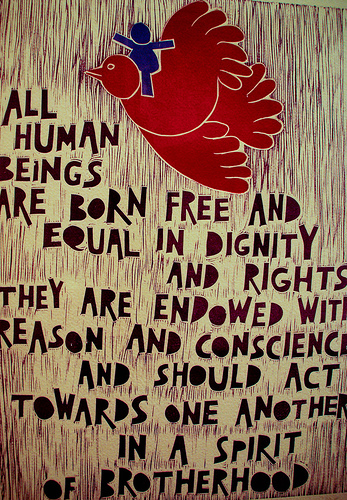

Freedom of religion is entrenched in international law, and in the charters of many countries – including Canada. In an increasingly multicultural society, how can we best protect this freedom of religion, while recognizing that some people also need freedom from religion? How do we accommodate the beliefs of some without trampling the beliefs of others? These are not easy questions to answer.

One way to approach this issue is to make a distinction between public and private places and public and private forms of religious expression. Few would argue that individuals should not have the right to display religious symbols in their homes or places of worship. A menorah on the mantle, a statue of the Virgin Mary in the garden, and a pentagram on the floor must all be given equal protection. In my view, religious symbols that individuals wear, or display on their personal vehicles, should also be afforded the same protection.

This becomes problematic, however, when one person’s symbol infringes in an unreasonable way on another’s person sense of self or personal security. Obvious examples include religious or even political beliefs that target minorities or promote hatred. For example, a line must be drawn prohibiting neo-Nazis from marching in the streets, or fundamentalist Christian churches from broadcasting messages of hate against gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgendered people.

Another option is to consider the question of whether it is possible for citizens to easily avoid being confronted with the religious messages in question. In the small community of Morinville, Alta., a debate is unfolding over an issue involving several non-Catholic families who believe that their children should have a secular alternative to Notre Dame Elementary. Morinville is a predominantly Catholic community and, other then giving in and sending their children to a Catholic school, parents who see some facets of Catholic education as conversion-oriented have no choice but to move. Freedom of religion – or, in this case, freedom from a particular religion – is not available, and this is clearly problematic.

It is also useful to distinguish between religious messaging that might be construed as proselytizing and that which is simply informational in nature. Religious organizations should have the right to place signage in public places, where other signage is allowed, to advertise services and community events. On religious buildings and properties, it is not unreasonable to expect religious slogans, citations from holy books, or even more direct recruitment messaging – so long as such messaging is lawful and not harmful to others.

It is also useful to distinguish between religious messaging that might be construed as proselytizing and that which is simply informational in nature. Religious organizations should have the right to place signage in public places, where other signage is allowed, to advertise services and community events. On religious buildings and properties, it is not unreasonable to expect religious slogans, citations from holy books, or even more direct recruitment messaging – so long as such messaging is lawful and not harmful to others.

When hammered into a tree at a public intersection, the “Jesus fish” symbol (known as the “ichthus”) fails to meet the three criteria discussed above, since many would see it as a form of proselytizing, in a public place, where avoidance of the message is impossible. This example of religious messaging also represents a dangerous and slippery slope; if the ichthus is allowed to appear in this fashion, how long will it be before religious messages like “Satan rocks” or “God is dead” show up on a street corner in your neighbourhood?

This article was originally published (March 28, 2011) in Gabriola Island's the Flying Shingle, here.

Photo (Fish Jesus) courtesy of Reuters.