THE FRAGMENTED SELF

I.J. Singh

My alternative title for this essay would have been “Think on Death – But Why?” But I stepped away from it because it might have fostered a black mood. That’s not my goal since I hope for a more optimistic stance of life – the essence of Charhdi Kalaa, a core value of Sikhi.

All life runs on two very diverse wheels of “wants” and “needs.” And it is no secret that these are often so apart from each other that they seem entirely contradictory. When they collide then our lives get redefined as split realities.

Making a living is a practical imperative of survival and a critical necessity. On the other hand, chasing happiness, socializing or plumbing the untold depths of spirituality, in other words, making a life may seem like an entirely unnecessary luxury. A balanced life, however, demands focus on both – making a living and making a life. Both preoccupations demand time, energy and commitment. If they are not in balance, it is fair to conclude that a life is seriously misaligned.

But there is a value index on every activity that we indulge in and that may vary for each of us. Each year around the beginning of a new year we resolve to reduce our passion for activities that may be wasteful of our resources, time and passion — and every year we fail.

What do people find more fulfilling? What matters most to them? The work that puts food on the table and guarantees a certain material lifestyle, or is it social activity, family connections or could it be something that is best labeled a spiritual path?

In this data driven world what do experts and talking heads tell us?

Around the celebrations for the New Year that dawned just a few weeks ago, Arthur C. Brooks, a columnist at the New York Times framed the relevant questions succinctly. I offer you a modified and abbreviated version of his queries.

If I had only a few hours or only this one year to live, he wondered, what would I do? Would I spend the next hour(s) mindlessly traveling the social media, would I spend time reading and contemplating something philosophical and uplifting, or would I think and do something that would leave my footprints in the sands of time after I am gone? Would recognition of death at the door make me grim and bitter or happily forgetful of the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune that I have tried mightily to ignore all my life?

How do you measure satisfaction in life? Brooks reasons that most likely people would place higher premium on their time at work-related activities, because they spend close to half their adult life on them. Or would our focus shift to the simple pleasures of life to fill the time available?

But, as he tells us in a 2004 report in Science magazine, a team of reputed scientists including a Nobel Prize winner (Daniel Kahneman) found that women reported higher satisfaction from prayer, worship and meditation than from watching television.

Yet, a decade later (2014), a report on labor statistics tells us the average respondent spent five times more time watching TV than engaging in spiritual activities, socializing, bonding or communicating with family and friends.

As one respondent quipped, “If I have one year to live, I’d run up my credit cards.” But that may not be a serious answer because surveys tell us that most people in that predicament do not run up their debt. In fact the looming death focuses their attention more on the present than on an uncertain and vague future.

As Benjamin Franklin noted, “Nothing focuses the mind quite as well as the prospect of a hanging.” Perhaps a year preceding an assured death is too long to actively and productively ruminate on the inevitable – the end of life. Here then is the crux of the misalignment between our needs and wants. I have not yet come across comparable data on men; but there is no reason to assume that results would be markedly different.

Humans often live in a largely imaginary past and pine for an unknown but rosier future; the present is thus lost in these two enduring pastimes. This is the crux of our misalignment — our existence between utopia and dystopia.

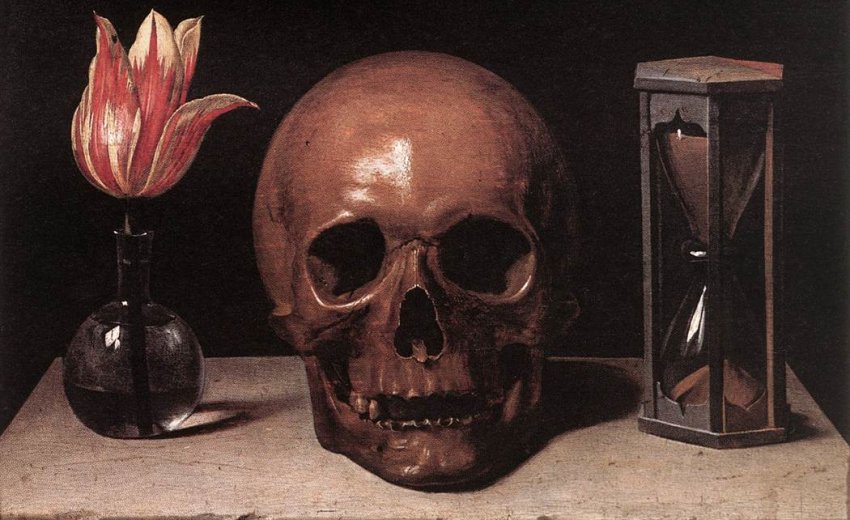

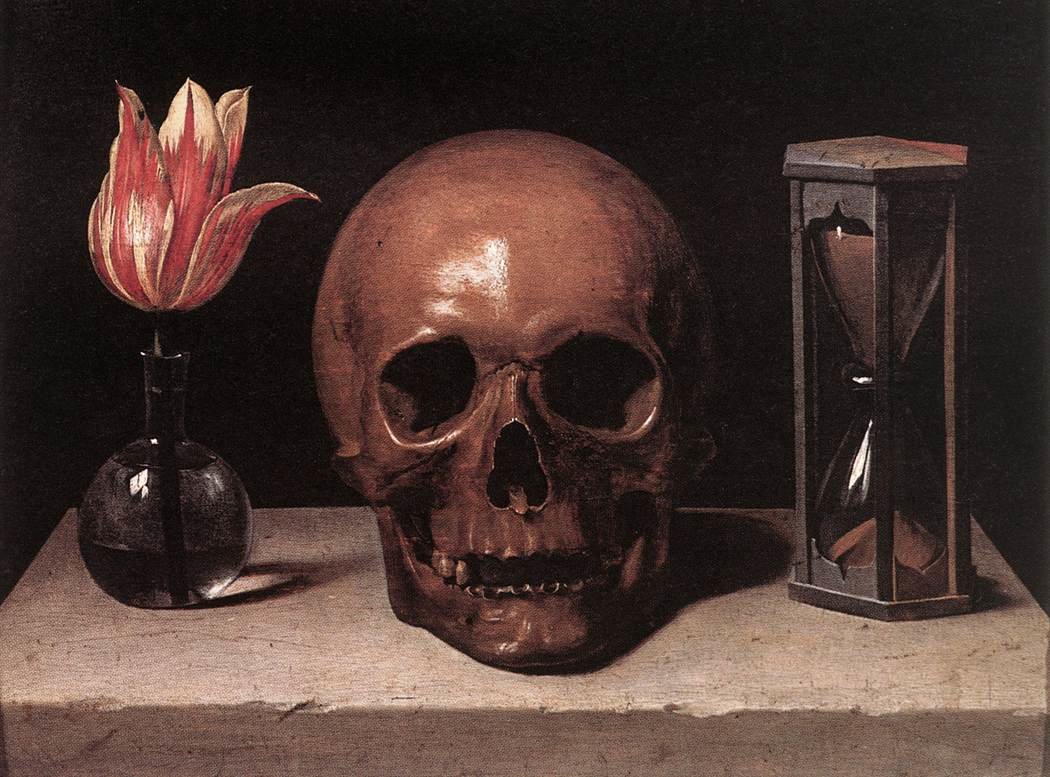

How then to retrain and rein in the mind and bring it to focus on the present. In Thailand, Buddhist monks meditate on dead bodies (corpses) to direct the focus to the present. This is meant to enable us to come to terms with the transitory nature of our puny, but not pointless, existence, indeed of all life.

Sikhi takes this issue head on. A plethora of citations can be mustered on this topic but I offer you only three to drive home my point. First the Guru Granth (p. 917) pointedly challenges us with “Eh sareera meriya iss jug meh aye ke kya tudh karam kamaaya” (What footprints will you leave in the sands of time?) and then it tells us (p. 1102,) “Pahila marn kabool kar jeevan ki chhudd aas” (Accept first the reality of death and abandon all hope of endless life.)

And then comes a most challenging, direct and enticing citation (p. 660), “Hum aadmi hae(n) ik dami…. (We humans are creatures of one single breath.) This tells us bluntly that life is really the one breath that one is engaged in at any given moment. The breath that preceded it is the past; the breath yet to be taken is the future, even though only a moment away. The breath we are in defines the present; and that alone is life. It is best then to live life in the present to its hilt in that single breath that defines the present. In fact, to me the idea of “Hukum” or divine will that pervades Sikh teaching means exactly that — living fully and productively in the moment.

Is it that easy? Not at all, but it is essential.

In Punjabi and related Indic languages the word “Admi” for a human can be parsed as “Aa” and “Dum” where Dum means breath and Aa stands for the first primal number, One. So, admispeaks to me of a creature of one breath — the singular reality of a single breath. Granted that I am not a linguist but it makes me wonder if the Biblical “Adam” and the Punjabi “Admi” are related terms that come to us from shared linguistic and philosophic antecedents and roots.

So, this new year, let’s stop worrying about the mundane and turn our attention to a realignment of our lives by becoming fully alive to the reality of this moment that stands between life and death. This means that we must have a relationship of deep trust with the unknown, the unseen.

January 25, 2016

Meditation on Death: "Bring your awareness to focus on something in your life that is changing or ending or dying right now. Breathe gently as you consider whatever transition is most significant right now in your life. Note any feelings that arise–trepidation, excitement, resistance, anger, annoyance, or grief. Every time your feelings get the better of you, become aware of your breathing. Meet your troubled and contracted feelings with your calm and expansive breath. Breathe, sigh, and stretch out on the river of change. Remember times when you have resisted change in the past. Regard how things turned out in the end- maybe not how you thought they would or you wanted them to, but in the end, there you were. Wiser, stronger, still alive. Tip your hat to the poignancy of death and the promise of rebirth. Smile. Relax. Allow yourself to break open. Sit tall, with dignity and patience, watching your breath rise and fall, rise and fall. Pray for the courage to welcome this new change with openness and wisdom.”

- Elizabeth Lesser