Scientists Forecast Dramatic Temperature Increase

The planet must not be allowed to warm beyond 2 degrees Celsius, according to the official targets at the Climate Change Conference in Doha. But a new study shows the goal is far from realistic. Current human activity is set to increase the temperature by some 5 degrees, and the consequences will be dire, scientists warn.

Normally, Christiana Figueres is thoroughly enthusiastic. The United Nations' top diplomat for climate changes issues uses her personal Twitter account to relay even the smallest advances in the fight against global warming with impressive euphoria. But recently, the Costa Rican hasn't been in the mood to celebrate. She has observed little interest or support for pushing governments to reach "ambitious and brave decisions," she complained after the first week of the UN Climate Change Conference in Doha, Qatar.

Normally, Christiana Figueres is thoroughly enthusiastic. The United Nations' top diplomat for climate changes issues uses her personal Twitter account to relay even the smallest advances in the fight against global warming with impressive euphoria. But recently, the Costa Rican hasn't been in the mood to celebrate. She has observed little interest or support for pushing governments to reach "ambitious and brave decisions," she complained after the first week of the UN Climate Change Conference in Doha, Qatar.

Her pessimism is justified. Since 2010, the official goal of negotiations has been limiting the increase in the earth's temperature to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), when compared to pre-industrial values, by the year 2100. Small island nations, who want to keep the increase even lower, have been pushing for a goal of 1.5 degrees Celsius. But scientists are certain that this can hardly be achieved any longer.

And now a new study has shown just how unrealistic the 2-degree goal is. "If we keep going on as we have been, it will be 5 degrees," says co-author Glen Peters, who works at Norway's Center for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO). And scientists agree that such a dramatic warming of the earth's temperature would have devastating consequences.

The Most Extreme Scenario

Together with Corinne Le Quéré of the UK's Tyndall Centre for Climate Change and colleagues from the Global Carbon Project, Peters calculated just how far apart international goals and reality are when it comes to climate change. Their conclusions, published in the scientific journal Nature Climate Change on Sunday, were the following:

Between 1990 and 2011, global emissions of carbon dioxide have increased by 54 percent, and this is expected to jump to 58 percent based on projections for 2012. Humans will have released some 35.6 gigatons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere in this year alone, with an average increase of 3.1 percent per year. That number was slightly lower in 2012, measuring 2.6 percent, though that was mainly due to the economic crisis, the paper says.

These emissions are in line with the most extreme scenario, dubbed "RCP 8.5," from the world climate report that will be presented in 2014. This means that realistically, it would take more than a decade for CO2 emissions to sink. But that would be too late to reach the two-degree target.

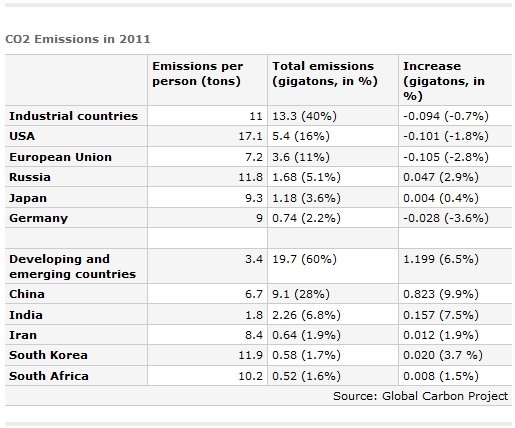

The biggest polluters are China, which produces 28 percent of global emissions, the United States with 16 percent, the European Union with 11 percent, and India with 7 percent, according to the study. Emissions levels went down in the last year in both Europe and the US, (1.8 and 2.8 percent respectively), but those improvements were cancelled out by an almost 10 percent increase in China -- an amount about equal to total emissions in Germany.

All Eyes on China

|

| DPA China has taken a great interest in green technologies like the solar panels shown here in the Tianjin Binhai New Area. But Beijing has refused to commit to any binding CO2 reduction pledges. |

The consequences of the projected increase of five degrees would be fatal. Researchers already expected that an increase of two degrees would result in glacial melt at the polar caps, and a dramatic increase in sea levels and droughts that would likely lead to waves of migration worldwide. All of this would be significantly more intense in the event of a five-degree increase of emissions.

China plays a key role in the scenario, with Beijing's decisions weighing heavily on the future of the world climate, according to the study's analysis. "There are strong arguments in favour of China doing more than it has in the past," Peters says. So far the country has resisted absolute CO2 reduction targets, pledging only to lower the amount of CO2 emissions released for every second product it manufactures. Targets also include reducing overall "energy intensity" by 45 percent by 2020 in the country.

|

| AP Researchers are warning that according to current carbon dioxide emissions rates, the world is headed for an average temperature increase of some 5 degrees Celsius. The result would be devastating, creating more droughts like this one in the Sahel region this spring, in addition to a host of other problems. |

|

| DPA According to rankings published by climate watchdog groups Germanwatch and the Climate Action Network, Germany has slipped to 8th place in the world in its efforts to fight climate change. |

|

| DPA Since 2010, the official goal of negotiations (shown here in Qatar last week) has been limiting the increase in the earth's temperature to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), when compared to pre-industrial values, by the year 2100. Small island nations want to keep the increase even lower, pushing for a goal of 1.5 degrees Celsius. But scientists are certain that this can hardly be achieved any longer. |

But given the strong growth of the Chinese economy, there is likely to be a hefty amount of additional CO2 emissions in absolute terms. Still, absolute reduction targets won't happen in China any time soon, because much like India, the country continues to point to its status as a developing nation, which grants it special treatment according to the UN's 1992 Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Nevertheless, the economies in developing countries continue to grow dramatically. While they accounted for 35 percent of the global CO2 emissions in 1990, that level was 58 percent in 2011. And when it comes to the level of emissions per person -- often used as a measure of a country's prosperity -- at 6.7 tons per year China has nearly reached the EU average of 7.2 tons per person.

Current Plan Unrealistic

Peters and other observers are convinced that advances in the international climate negotiations can only come from developing and emerging economies, however. Should they choose to participate, it could significantly increase pressure on the US. Last year's extension of the Kyoto Protocol is useless by contrast, Peters says, pointing out that only European countries and Australia are taking part.

Meanwhile, more conflict has arisen during the conference in Doha because countries like Poland and Russia are insisting that they be able to sell unused pollution rights worth a total of 13 gigatons of CO2 in the future.

In the best case scenario, a second phase of the Kyoto Protocol would preserve the political mechanisms like emissions trading until a new global climate agreement can be reached, Peters says. But according to the current plan, that won't be until 2020. "Because of the timetable alone, delegates are already negotiating at levels well over two additional degrees," the researcher warns. "The negotiating text is inconsistent with the target."