|

| Photo: In Senegal in 2007, advocates used plays, singing and dancing to encourage villages to stop female excision, which was still practiced despite a ban. Credit: Robyn Dixon / Los Angeles Times |

Eight thousand communities in Africa have sworn off female genital excision, including almost 2,000 that abandoned the practice in the last year, the United Nations Population Fund and UNICEF announced Monday.

In some northern and eastern stretches of Africa and the Middle East, cutting the female genitals is seen as a coming-of-age ritual that ensures chastity and makes a woman marriageable. U.N. agencies have pushed to end practices that cut away all or part of female genitalia, saying they have no health benefits and cause severe pain.

There are also long-term risks for women who undergo cutting: The World Health Organization says female circumcision can increase the risk of childbirth complications, cause recurring infections or create the need for later surgeries to allow for sexual intercourse and childbirth.

Over the last year, Kenya and Guinea-Bissau passed laws banning female genital excision. In Ethiopia, Senegal and other African countries, thousands of villages have publicly declared that they were against it. U.N. agencies spent more than $6.1 million last year to combat the practice.

The Times' Robyn Dixon wrote about genital cutting five years ago, interviewing a Senegalese former "cutter" named Oureye Sall who said girls used to flee at the sight of her face:

She inherited the trade from her mother and made a tidy profit: a dollar per operation for the practice known locally as "cleaning," and in much of the rest of the world as female genital circumcision, or mutilation. Sall broke each razor blade in two for economy's sake and used each half until it was too blunt to cut properly. Sometimes she did 15 or 20 operations a day, other times two or three. She has no idea how many girls she cut in her decades-long career.

"Of course the girls would fight," she said of the procedure, in which she sliced off the external sexual organs. "Of course they would hit you. They would cry, they would kick.

"But you'd have three good strong women to help you. Someone had to actually sit on each leg and someone had to control the arms and upper body. We would cover their mouths. You don't want the neighbors to hear."

As African and Middle Eastern immigrants have resettled elsewhere, the practice has spurred debate there as well. Ireland, for instance, has proposed legislation that would criminalize female genital excision. It's already illegal in Britain, Scandinavia and much of the rest of Europe.

But physicians have sometimes argued that minor cutting should be permitted as a cultural practice. The American Academy of Pediatrics caused a stir two years ago when it suggested that U.S. doctors should be able to make a ceremonial pinprick if it would keep their families from sending them abroad for more drastic cutting. It retracted its statement after outpourings of criticism from advocacy groups.

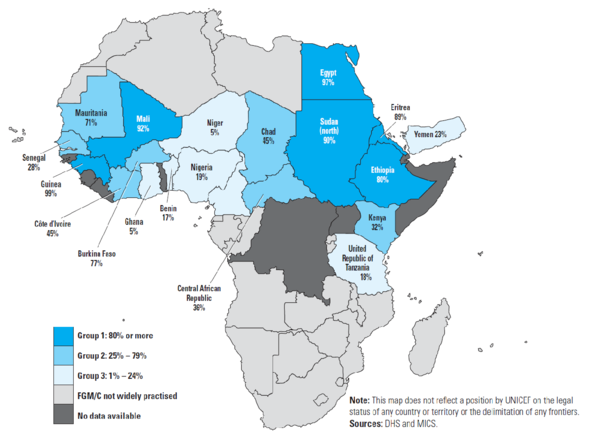

Female genital excision has long been the norm in much of eastern Africa. In 2005, UNICEF produced this map indicating the frequency of the procedure on females ages 15 to 49 across Africa: