A stunning example of artistic expression can be found adorning the walls of the famous Gurdwara Baba Atal Sahib Ji.

Sikhism is well-known for its belief system, the culture of seva and warfare. However, one fact that isn’t talked about much is the tradition of art and literature in the religion. Let’s delve into the work of art at the gurudwaras.

Painting, a delicate art form, allows humans to express thoughts and emotions through lines and colours. Its roots trace back thousands of years, to a time before recorded history, when early humans adorned their cave dwellings with images. As civilization progressed, so did the practice of painting, evolving into mural art, where large surfaces like walls and ceilings became canvases. Over time, various techniques emerged, such as fresco and fresco-secco, enriching this art form. Through the ages, painting has captured cultural values and depicted the truths of life. In the Indian context, one immediately thinks of the awe-inspiring murals of Ajanta. These masterpieces reflect a profound appreciation for beauty and form, portraying the splendour of the Buddha's life.

The painters of Ajanta used the story of Buddha as a motif to illustrate the timeless essence of human existence. Throughout India, murals have adorned temples, gurdwaras, and other religious sites, serving as guardians of cultural and spiritual heritage.

Murals at gurudwaras

In the Gurdwaras of Punjab, particularly in the revered city of Amritsar, a stunning example of artistic expression can be found adorning the walls of the famous Gurdwara Baba Atal Sahib Ji. This gurdwara, a nine-storeyed octagonal tower, was constructed in 1620 A.D. in honour of Atal Rai, the son of the sixth Guru, Guru Hargobind. Originally a modest memorial housing the remains of Atal Rai, it was later transformed into a grand gurdwara with nine storeys symbolising the nine years of Atal Rai's brief life. Despite his young age, Atal Rai was bestowed with the title of Baba due to his remarkable wisdom.

Punjabis hold a deep reverence for wisdom and spiritual insight, particularly towards the first Guru, Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji. Consequently, the interior walls of the first floor of Gurdwara Baba Atal Sahib Ji are adorned with intricate murals depicting the Janam Sakhis of Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji. These Janam Sakhis or birth stories, provide a biographical account of Guru Ji's life, shedding light on his profound philosophical teachings and how he imparted them. These murals serve as a visual representation of the early period of Sikhism and the foundational principles established by the first Guru. Their beauty resonates deeply with viewers, inspiring acts of kindness and love while imparting enlightenment and knowledge, regardless of the viewer's literacy or education level. Through their harmony and vivid depiction, these murals offer a glimpse into the essence of life and uplift the spirit of those who behold them.

Sacred paintings

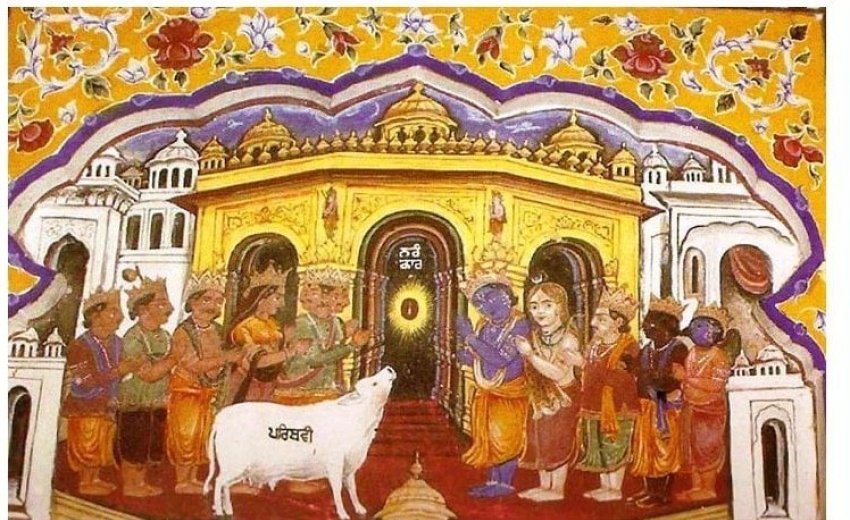

Influenced by the famous Bala Janam Sakhi penned by Paida Mokha, artists Jaimal Singh Naqqash, Mehtab Singh Naqqash, and Hukum Singh embarked on a sacred endeavor within the Gurdwara. Their mission was to adorn its walls with divine paintings, depicting a scene where celestial beings beseech the formless Almighty, Nirankar, to send a benevolent soul to relieve Earth from the woes of Kala-yuga. At the centre of this artwork shines the radiant light from Sachkhand, the Abode of Truth. All the gods and Mother Earth, in the form of a cow, stand in reverence, awaiting the arrival of the divine incarnations.

Their prayers answered, their invocation heeded, the divine child is born. His parents, Kalyan Rai Bedi and Tripla Ji, are overwhelmed with joy and gratitude. Pandit Hardiyal, the family priest, christens the newborn Nanak Nirankari, signifying his true essence as Nirankar. Recorded in history as the 15th of April, 1469, at Raibhoi Di Talwandi, this auspicious event marks the dawn of a new era.

Also, another painting shows the child Nirankari is brought out by his father Kalyan Rai in the daylight. All the gods who prayed for His Avatar are now eager to catch a glimpse of this divine incarnation. The painting depicts these gods experiencing sheer joy as they witness the Eternal Light embodied in the form of a child. The earth and sky radiate with the glory of this divine birth, vibrating with energy. The artists skillfully portray this atmosphere, showing gods showering flowers from the heavens while musicians on earth play sacred music in harmony with the celestial petals. All present, including the gods and esteemed guests, bow in reverence to this eternal light, as if collectively chanting praises:

“Dhan Guru Nanak Pargatia Miti Thund jag Chanan Hoyaya”

The following paintings

The artists move on to the next phase of Guru Nanak's life, envisioning him as a young child attending school. At the age of five, he learns Hindi from Gopal Pandit Ji, and a year later, he studies Sanskrit under Pandit Brij Nath. By the age of seven, he was sent to school to study Persian under Mullah Kutubin's guidance. In one painting, he sits with his father, Baba Kalu, in front of Mullah Kutubin, surprising him with his understanding of the first letter of Persian, Alaph. To bring this scene to life, the artists depict other students engaged in activities such as cleaning their wooden slates or eagerly awaiting their turn to present their work to the Mullah.

Other paintings capture various moments from Guru Nanak's life, including his refusal to wear the sacred thread, his acts of tending cattle, and his generosity in distributing sweets to children and holy individuals. Through these depictions, Guru Nanak's deep love for all beings and his unwavering commitment to his beliefs shine forth.

Nanak’s childhood

As Nanak grew up, he was filled with a deep desire to help others with his kind heart. When he applied his wisdom to everyday life, it led to the establishment of Sacha Sauda, meaning 'True Business'. Legend has it that one day, Nanak received Rs. 20 from his father to start a business. Alongside his friend Bhai Bala, he set out for a town to begin trading. On their journey, they met some holy monks known as Sadhus, who asked for food. Nanak decided to use the money to feed them instead, believing it was a worthy use of his funds. This act marked the beginning of what later became known as langar sewa, a tradition of providing free meals to the needy and poor, popularized by Nanak. In the depicted scene, Guru Nanak is engaged in a discussion with the Sadhus' leader, while Bhai Bala and other Sadhus listen attentively. The artist captured the emotions, gestures, and postures of the figures with great skill and detail, conveying the reverence of the moment.

After completing his transaction, when Nanak went back to Talwandi, he was scared of his father's punishment. The painting depicts him hiding in the bushes in the jungle. Legend has it that the tree where Nanak hid is still standing and carefully looked after. This tree is known as Tambu Sahib, meaning Holy Trunk.

At the age of 17 years , Nanak moved to Sultanpur to work as a storekeeper at a place called Modikhana, owned by the Nawab. Even in this role, he continued his practice of helping the needy by giving them wheat, rice, and sugar from his own money, following the principles of true business. His pure heart enabled him to see the presence of God in everyone, even amidst his daily tasks. Whenever the number thirteen appeared in any transaction, Nanak would enter a state of deep meditation, chanting "Tera, Tera" which means "Yours, Yours," acknowledging everything belonged to the Divine. This practice drew many people to the store, who admired Nanak for his kindness and spiritual insight.

Janam Sakhi paintings

Janam Sakhi paintings, renowned for their beauty, intricately intertwine mythological characters with profound symbolic meanings. In one captivating piece, the story of Varun Devta and Guru Nanak unfolds, imbued with the richness of symbolism.

The painting portrays a pivotal moment in Guru Nanak's life when, during deep meditation, he received divine guidance to embark on his earthly mission. The following morning, accompanied by Bhai Bala, he ventured to the Bain river, where he shed his worldly attire, leaving only a simple cloth. Illustrated in the artwork, Guru Nanak submerges into the river, symbolising his immersion into spiritual realms, with only his feet visible. Standing nearby is Varun Devta, a celestial messenger, depicted with folded hands, poised to welcome Guru Nanak and guide him to the realm of Nirankar or Sachkhand.

On the right side of the painting, Guru Nanak is depicted being carried on a palanquin, symbolising his journey to meet Nirankar. A doorway to Sachkhand signifies his spiritual discourse with the divine. Meanwhile, on the far left, Guru Nanak emerges from the river after three days of spiritual communion, encountering his brother-in-law, Jai Ram, showcasing his return to the earthly realm. Bhai Bala sits sorrowfully, mourning the temporary loss of his beloved master.

Symbolically, it represented a profound journey into the inner self, the supreme soul, The Nirankar. From that moment, Nanak became known as Nanak Nirankari. The enlightenment bestowed upon Guru Nanak imbued him with magical abilities, depicted in various paintings showcasing his miraculous powers. Examples include his encounter with Nag: Sarap Chhaya, the scene of Grazing Cattle, the Revival of an Elephant, and his Visit to Bhai Lalo. These paintings capture the essence of Guru Nanak's extraordinary persona and his role as a protector of the world.

The Painting-Grazing the Cattle

In a serene pasture depicted in the painting, the scene unfolds where Guru Ji’s cattle stray into a neighbouring farmer's fields. According to the tale, Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji once tended to buffaloes in these pastures. While resting under a tree during this task, Guru Ji began to meditate, as portrayed in the artwork. Meanwhile, the buffaloes wandered off into the neighbouring fields, causing damage to the crops.

Upon discovering the ruined fields, the farmer, understandably upset, lodged a complaint against Guru Nanak Dev Ji with Rai Bular, the local authority. To address the issue, Rai Bular dispatched servants to investigate. However, to their surprise, they found the fields untouched upon arrival. This painting captures a significant miracle attributed to Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji. Through expressive gestures, charged facial expressions, and dynamic depictions of buffaloes and cows, the artist brings the scene to life. The historical site of this event is now revered as Gurdwara Kiara Sahib.

Nag Sarap Chhaya is a remarkable painting depicting a Cobra protecting Guru Nanak by spreading its hood like an umbrella. This imagery has been a recurring motif in the art history of India, revered by Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains alike. Legend has it that one day, Guru Nanak took his cattle to graze in the fields. While they grazed, he immersed himself in deep meditation under a tree. That very tree still stands today. One afternoon, Rai Bular, a village chieftain, and his officers passed by and were astonished to see the Cobra's hood casting shade over Guru Nanak. This extraordinary sight convinced them of Guru Nanak's divine nature, recognizing that he was no ordinary child.

Feast by Malik Bhago

Another painting showcases a feast organised by Malik Bhago, a notable government official in the city of Saidpur, now known as Eminabad in Pakistan. The event is based on a tale where Malik Bhago, known for his cruelty and greed, invites Guru Nanak Dev Ji, a revered spiritual figure, to a banquet. Initially, Guru Nanak declines, stating that as a Fakir, he has no interest in feasts. However, upon persistent insistence, Guru Nanak accepts, accompanied by Bhai Lalo Ji, a humble carpenter.

Malik Bhago, feeling disdainful, criticises Guru Nanak for dining at a carpenter's home, considering it beneath his status as a Kshatriya. In a symbolic act, Guru Nanak takes a chapatti from Bhai Lalo with one hand and Malik Bhago's fried food with the other. When squeezed, milk flows from Bhai Lalo's chapatti, while blood oozes from Malik Bhago's food. This act serves as a poignant lesson, illustrating that honest earnings, represented by Bhai Lalo's chapatti, yield pure sustenance, while corrupt gains, depicted by Malik Bhago's food, result in suffering and bloodshed.

The painting masterfully captures this profound moment, emphasising the contrast between blood and milk, the expressive gestures of the characters, and the overall message of earning a livelihood with integrity. Through vivid imagery and meticulous detail, the artist conveys the timeless wisdom of prioritising honest means of sustenance.

A painting depicting the inevitable cycle of life and death

In one of the paintings, there's an inscription that reads "Baba Ji Nai Hathi Jinda Kita" which translates to "The saint revived the elephant." According to a Sakhi, a traditional Sikh story, Guru Nanak once journeyed towards Delhi. As he approached the outskirts of the city, he encountered an elephant owned by the Emperor that had passed away. The elephant's keepers were distressed, fearing punishment from the Emperor.

Upon hearing of the Guru's arrival, the keepers beseeched him to bring the elephant back to life. Guru Nanak responded with a lesson on the divine nature of life and death, stating that it's not for humans to interfere with God's will. However, out of compassion for the keepers, he relented and revived the elephant.

When Emperor Ibrahim Beg learned of this miracle, he approached the Guru and asked if it was indeed him who brought the elephant back to life. The Emperor then requested another miracle, asking Guru Nanak to make the elephant die again, which the Guru did. When the Emperor insisted on its revival once more, Guru Nanak declined, explaining the sanctity of God's will and the dangers of playing with divine power. This incident brought relief to the elephant's keepers, as the foolishness of the Emperor led to the elephant's demise. It is believed that a Gurdwara stands at the site of this event, commemorating Guru Nanak's teachings and the lesson of divine wisdom over human intervention.

With Firanda

Religious poetry set to music, particularly on the rabab, a stringed instrument, plays a vital role in Sikh rituals and worship. Legend has it that Guru Nanak Dev Ji's close companion Mardana, who was both a musician and a skilled rabab player, embarked on a quest to find the perfect rabab. One version of the tale suggests that after an extensive and unsuccessful search, Guru Nanak directed Mardana to Firanda, a talented carpenter and musician. In another rendition, Mardana, seeking to replace his worn-out instrument, stumbled upon a superb rabab crafted by the artisan Firanda. Upon learning that the rabab was intended for Guru Nanak, Firanda requested the opportunity to meet the Guru instead of accepting payment. He then presented his special rabab to Guru Nanak Dev Ji, which produced a divine melody when played—a tune that resonated with spiritual praise.

Sat Kartar, Toon Nirankar

In the painting, Guru Nanak Dev Ji, easily recognized by the glowing circle around his head, is depicted sitting beneath a tree, deep in conversation with Firanda and Bhai Mardana. The central focus of the painting is the rabab, an important musical instrument, placed prominently.

Moving on to the next series of paintings, they showcase Guru Nanak’s wedding ceremonies. These include various rituals such as Kudmayi, Shagun, Khare Te Ishnam Karma (Guru Nanak ceremonially bathing before his wedding), Barat (the procession) of Guru Nanak Ji, during which Bibi Nanaki asserts her rights as his sister, Barat reaching Batala, Guru Nanak Ji sharing Langar (community meal) with the Sangat (community), Lavan (wedding rounds), Doli (palanquin), Groom’s return to his house with his bride, and Mata Tripta Ji welcoming the newlywed couple. Each of the nine paintings by the artist meticulously portrays the customs and traditions observed in an Indian, particularly Punjabi, wedding.

One standout painting in this collection depicts the Betrothal Ceremony, where a priest from the bride’s side officiates. Set in Nanak’s home, the scene captures Nanak and his male relatives eagerly awaiting the arrival of the bride's family. Traditional greetings are exchanged with folded hands, and sweets are shared in joyous celebration. Mula, the bride’s father, presents Shagun (auspicious token) to Nanak. In the painting, Nanak appears contemplative, as he reassesses the person who will soon become the husband of his beloved daughter Ghuni, entrusted with her happiness and security.

Nanak’s wedding celebrations

In one painting, Guru Nanak Ji sits on a horse, getting ready to go to a wedding. His sister, Bibi Nanaki, holds the horse's reins and blesses her brother on his special day. It's a tradition for grooms to give valuable gifts to their sisters on such occasions because sisters hold a unique and cherished place in their hearts. The next set of paintings shows Guru Nanak as a teacher. He travelled extensively, meeting with people of various faiths and beliefs, including Fakirs, Pandits, and even the Mughal Emperor Babur. Guru Nanak shared teachings of love, truth, honesty, and inner purity wherever he went. He was also known for his ability to perform miracles, such as reviving a withered tree with just his touch. Once, during a visit to Gorakh Mata in the Himalayas, he turned the sour fruit of a Ritha tree into a sweet delicacy, showing his miraculous powers.

In one painting, Guru Nanak is depicted having a discussion with Gorakh Nath, a prominent Sadhu, under a Peepal tree. The tree, once withered and dry, came back to life with Guru Nanak's touch, symbolising his divine connection with nature. Even today, the Ritha Sahib tree, located forty-five miles away, continues to bear sweet and edible fruits since Guru Nanak blessed it.

At Hasan Abdal

During their journey to Kashmir, Guru Nanak Dev Ji and Bhai Mardana made a stop at Hasan Abdal. Resting under a shady tree, they began singing hymns, attracting devotees to join them. This didn’t sit well with Wali Quandhari, a holy man residing atop a nearby hill. Meanwhile, Bhai Mardana grew thirsty, prompting Guru Ji to send him to Wali Qandhari for water. However, Wali Qandhari, refusing to help, sent Mardana back empty-handed. To relieve Mardana's thirst, Guru Ji miraculously created a spring by striking the ground with a piece of wood. Simultaneously, Wali Qandhari's own water source dried up.

Enraged, Wali Qandhari attempted to crush Guru Ji with a massive boulder, but Guru Nanak Dev Ji effortlessly stopped it with his hand, leaving an imprint on the stone. This imprint, known as Panja Sahib, holds significance for Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims alike. Witnessing Guru Ji's display of divine power, Wali Qandhari humbly begged for forgiveness and blessings. Moved by his sincerity, Guru Ji imparted the universal message of compassion and kindness, urging Wali Qandhari to embrace a life filled with love for God and goodwill towards all beings.

At Kurukshetra

A significant painting depicts Guru Nanak at Kurukshetra during a solar eclipse. The inscription on the painting explains that Guru Nanak visited Kurukshetra and stayed there during the eclipse. He aimed to educate people about the eclipse, emphasising that it's a natural event unrelated to religion. Guru Nanak highlighted that the darkness during an eclipse is caused by the alignment of planets, stressing its scientific nature rather than any religious significance.

The painting showcasing a ‘Meeting’

After closely examining these paintings, one can notice that Guru Nanak's family is notably absent in most of his depictions during his travels, except for one significant visit to his sister's home in Sultanpur. Known affectionately as Bebe, which translates to a respected and wise person, Bibi Nanaki was the first to recognize Guru Nanak's spiritual divinity. She was not only his sister but also his first disciple.

Legend has it that while Guru Nanak was far away in the Middle East with his companions Bala and Mardana, Bibi Nanaki longed to see him. She began preparing a traditional meal of corn flour chapatis and mustard greens, recalling Guru Nanak's promise to visit her whenever she wished. Feeling a sudden urge, Guru Nanak interrupted his journey and returned to Sultanpur halfway through his travels. Upon reaching her door, Bibi Nanaki was astonished to find her brother standing there with Bala and Mardana. Overwhelmed with emotion, she touched Guru Nanak's feet as a mark of deep respect and gratitude for his blessings. She expressed her profound longing for his presence, to which Guru Nanak responded with understanding, acknowledging the depth of her feelings.

In one such painting depicting this heartfelt reunion, Guru Nanak is portrayed seated with Bala and Mardana, while Bibi Nanaki sits in the centre with folded hands alongside her husband, Jai Ram. A maid and Guru Nanak's son, Sri Chand, are also depicted, showing reverence with folded hands towards Guru Nanak and Bibi Nanaki.

Bhai Mardana

One of the most significant paintings portrays the journey of Bhai Mardana, a close companion of Guru Nanak Dev Ji, known for his mastery of music. Mardana accompanied Guru Nanak on all his travels, spreading spiritual teachings through their journeys. According to various accounts, there are differing versions of Mardana's passing and final rites. In one version, Guru Nanak and Mardana travelled to Khurrum, located in Central Asia. During the journey, Mardana fell ill and passed away unexpectedly. Guru Nanak, along with Bhai Bala, performed Mardana's last rites with utmost respect and honour.

In another popular account, Mardana expressed his desire to return home. He shared an encounter where he received a garland of everlasting flowers from divine beings called Gandharvas. Guru Nanak recognized the significance of the encounter and the approaching end of Mardana's life. In yet another version, Guru Nanak foresaw Mardana's illness and impending death. He offered Mardana the choice of burial with a grand tomb, to which Mardana, fully immersed in Nanak's teachings, responded by expressing his detachment from worldly fame and material possessions. In accordance with Mardana's spiritual inclination, Guru Nanak decided to release his body into the Ravi River, symbolizing liberation from earthly attachments.

Regardless of the specific account, the essence remains the same: the profound bond between Guru Nanak and Bhai Mardana, transcending life and death, symbolizing spiritual enlightenment and detachment from worldly desires.

In this painting, you can see Guru Nanak Dev Ji sitting under a tree, holding a simrani in his left hand, and reciting verses from Kirtan Sohila. This particular prayer is often recited during funeral rites to guide the departed soul. Nearby, Mardana's lifeless body lies on the ground, covered in a white sheet known as khafan, with his rabab, the instrument he played, placed under his head. Bala is depicted gathering wood for Mardana's funeral pyre. The artist has captured this scene with remarkable accuracy, portraying the event in detail. The inscriptions in Gurmukhi on the painting help to identify and explain the illustration further.

Baba Budda

The final series of paintings illustrates how Guru Nanak chose Bhai Lehna as his successor, passing on the divine Guru-Mantar, symbolizing the transfer of spiritual energy. One painting depicts Baba Budda applying the Guru Gaddi Tilak to Guru Angad Dev Ji, under the gaze of Guru Nanak Dev Ji. Guru Nanak bestowed the name Angad upon Bhai Lehna, signifying their intimate spiritual connection. Baba Budda Ji, also known as Baba Budda, had the esteemed role of anointing five of the ten Sikh Gurus. He presented Guru Angad Dev Ji with symbolic offerings, including a Bani-Pothi, a collection of hymns, and a rosary, marking the continuation of Guru Nanak's legacy.

The fresco technique used in the Gurdwara of Baba Atal exhibits influences from neighbouring regions like Rajasthan and the Hill states. Referred to as Mohrakashi in Punjab and Haryana, the technique shares similarities with Jodhpur's artistry, hence called Jodhpuri Hunar. Unlike the secco technique, where the plaster dries before painting, fresco involves painting on wet plaster. This method is exclusively employed in the murals adorning the walls of the first floor of the Gurdwara of Baba Atal.

Fresco paintings in ancient times used mineral colours, which were kept moist in earthen pots. Bhai Gian Singh Naqqash mentioned that only six colours were used: red, green, blue, yellow, black, and white. Different shades were achieved by mixing these colours, except for green, which required yellow clay. Red came from a clay called hurmachi, sourced from hills and sold by grocers. It was ground on stone slabs while kept moist. Green was made from terra-verte chips mixed with water. Yellow came from yellow clay, blue from lapis-lazuli, and deep blue from indigo. Black was derived from coconut crust or burnt mustard oil smoke. A white substance called doga, akin to curd, was made by filtering water through burnt marble chips. Brushes, called qalams, were crafted by artists from squirrel tails or goat and camel hair. Throughout the painting process, colours were kept moist in earthen pots.

These early Sikh paintings were groundbreaking. They unleashed the creativity and potential of Sikh art, introducing new fictional dimensions and a deep spiritual undercurrent. They established the artistic vocabulary of Sikhism: portraits of Gurus, depictions of historical events, dynamic action scenes, narrative sequences, landscapes, symbolic imagery, and a balanced use of colour. The meticulous details, refined borders, and overall graphic design showcase a nascent art form with a unique identity. These paintings reveal a cohesive tradition with remarkable resilience, resisting outside influences and forging its own path. They offer a window into the rich social and cultural mosaic of the heritage of the 16th-century Punjab.

*Based on an article written by Dr. Jiwan Sodhi, published in The Sikh Foundation on 13th May 2014