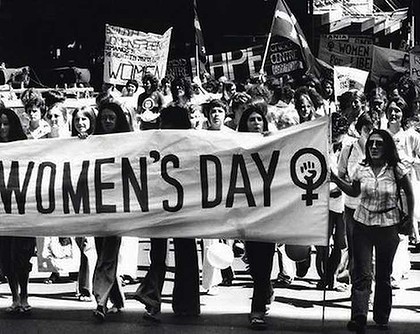

NEW YORK — Just as many women in the United States are feeling under assault from conservatives threatening to impose restrictions on abortion rights and even contraceptives, the groundbreaking agency U.N. Women is marking its first year and hundreds of firebrands and activists are convening here for the third annual Women in the World meeting.

In the view of Tina Brown, a founder of the Women in the World foundation, and editor of Newsweek and The Daily Beast, the women’s movement is very much global. Indeed, she noted, “much of the movement today is coming in emerging nations,” in places like Uganda or the Arab world.

“They face challenges we can’t even begin to imagine,” Ms. Brown said.

Meanwhile, American women have gone through a horrific period, she said, their dignity under attack and their long-held rights at risk. “America has been put to shame,” she said. “American women now have to look overseas for inspiration.”

Over three days this week, women’s leaders like Hillary Rodham Clinton, the U.S. secretary of state, and Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, will share the spotlight with unheralded village women and their tales of travail and bravery.

Those stories will seem remarkably familiar to Michelle Bachelet, executive director of U.N. Women and a former president of Chile, who knows firsthand the global struggle. From her platform at the United Nations, Ms. Bachelet oversees offices in 75 countries, playing a part in improving the lives and livelihoods of millions of women.

“The biggest challenges everywhere,” she said in a recent interview, “are political participation and economic empowerment — and ending violence against women.”

No country is spared. Even in the most advanced countries, she said, where women have been elected presidents or prime ministers, female candidates are still subjected to sexist jokes and comments, salary gaps persist, and there are too few women in major public and business positions.

Female quotas in business and politics are relatively common. Electoral gender quota laws, however, do not seem to have smoothed the political path for women in Latin America, where at least 14 countries have quotas.

But there’s a paradox. Female leaders or heads of state are not rare in Latin America. Today, women are presidents in three countries — Brazil, Argentina and Costa Rica — and 50 percent belong to political parties, but only 19 percent hold top positions.

On the leading edge stand Argentina and Costa Rica, but Cuba, with no quotas, is at the head of the class. Yet Brazil barely scrapes by, with a below-par performance that may improve under Dilma Rousseff’s leadership. (Quotas would find little favor in the United States, where women are only 16 percent of the 435 members of the House of Representatives and 17 percent among the 100 members of the Senate.)

“I can’t stress enough why women’s political participation is important,” Ms. Bachelet said. “It is, of course, because it’s the right thing to do, because it will create better democracies, and because it’s an opportunity to bring fresh air to politics and new types of leadership. For me, a better democracy is a democracy where women do not only have the right to vote and to elect but to be elected.”

But obstacles conspire against women. There’s the so-called economy of care that still expects women to look after the children, the elderly, the husband, the home. Then there’s ambition.

“It isn’t that women are less ambitious,” Ms. Bachelet said, “but women want to find a balance between work, love, and family.”

When a man is dedicated to his job or politics, he is respected, but when a woman does the same thing and has kids, she’s a bad mother.

“So there are cultural expectations, demands, and, if I may say, even some social punishment for women who make those choices,” Ms. Bachelet said.

In some parts of the world, it is much worse.

“Women do not have citizen’s rights,” Ms. Bachelet said. “Women do not have land’s rights. Women should not be seen alone with a man in the street. You see women who are thrown acid in the face because they don’t accept a marriage proposal or are killed because they don’t give birth to a boy. You see parents who give away a daughter for money or sex.”

And women and girls are 80 percent of those trafficked for sex and labor slavery.

“Women are usually invisible in society,” Ms. Bachelet said.

An agnostic and a Socialist, a single mother of three who survived arrest and exile in the Pinochet era, Ms. Bachelet was given little chance to win the presidency in Chile, a conservative, Roman Catholic country. She recalled, “People would say, ‘She’s very nice, but she’s not capable, she doesn’t have the character to be president’ — and worse.”

So when Ms. Bachelet was elected the first female president of Chile, in 2006, she set out to create an egalitarian government. It reshaped Chilean policy and culture, and when her term ended by law, in March 2010, her popularity rating had topped 70 percent. These days she visits Chile quietly, in order not to stir rumors, which she denies, that she will return to run in the 2014 presidential election.

For now, she has taken on a sometimes frustrating and wearying load.

“We have advanced,” Ms. Bachelet said. “We are more socially aware, we are certainly far better off than 10 years ago. There’s no way back, but this is not enough.”

UN Women Executive Director, Michelle Bachelet on video:

|

|

| On International Women's Day, 8 March 2012, UN Women Executive Director Michelle Bachelet calls for women's equal participation in all spheres of life as fundamental to democracy and justice. See also her written statement at http://www.unwomen.org/?p=11731. For more information on International Women's Day, visit http://www.unwomen.org/how-we-work/csw/csw-56/iwd/ |