February 20, 2014: The Quebec government’s proposed “Charter of Values” legislation has aroused reactions from around the world. We can gain a greater perspective on how immigrants to Quebec are treated today if we look at how immigrants were treated here 50 or 60 years ago.

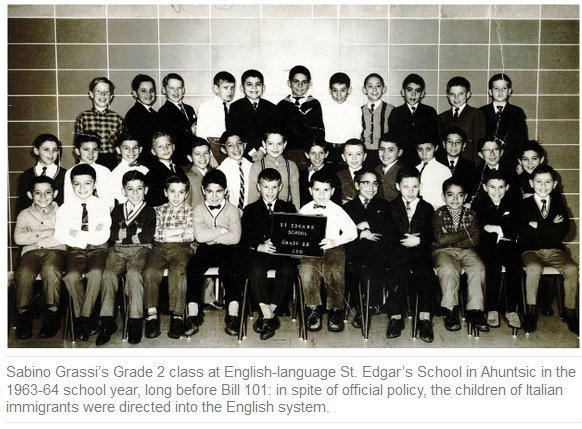

During the 1950s and 1960s, the largest group of immigrants to Quebec were from Italy.

My parents arrived in Montreal from Italy in 1952. Like most Italians arriving then, they knew no English or French. However, given that French has the same Latin roots as Italian, French was the language that they could actually understand to a limited extent, so most Italian immigrants began to learn it.

It wasn’t long before young Italo-Canadians like me were born. Given that our parents were only beginning to learn French, Italian was the language that was spoken at home and Italian became the first language we learned as kids.

By the time I turned 6, my parents had developed a working knowledge of French. English was still completely “foreign” to them. So when it came time to choose a school, like the vast majority of Italians back then, they chose a French school. And were rejected.

“It was not our choice,” my mother told me later. “We tried to enrol you in French school because we wanted to be involved with your education and help you with your homework. With no knowledge of English, French school would have been our preference. We were turned away by the French school near our house; they told us to take you to the English school.”

She said she was never given a reason — but that it was obvious to her that French people, or at least some French people, didn’t like us Italians back then.

In the 40 years since, I have made it a point to ask all my Italian friends and relatives, who were virtually all in the English system, why they were not in the French system. The vast majority had experiences similar to mine.

I decided to research how school-board decisions were made 50 years ago. I started in the archives department of the Commission des écoles catholiques de Montréal and looked through boxes of documents, expecting to find debate and decisions at the school-board level about acceptance (or rejection) of immigrants, notably Italians, in the French system.

What I found instead was surprising.

The minutes of CECM meetings in the late 1950s reveals that the elected commissioners were obsessed with trying to understand why so many immigrants, particularly Italians, were opting to send their kids to English schools and not choosing French schools.

It is clear that these commissioners would have preferred that more Catholic immigrants had chosen the French system. But it’s equally clear to me that this desire was being widely ignored (sabotaged?) by the principals and administrators in the French schools at that time.

I also came across numerous references to a “myth” about immigrants being rejected by the French system during those years.

Miguel Andrade of the history department at the Université du Québec à Montréal recently published an excellent article titled La Commission des écoles catholiques de Montréal et l’intégration des immigrants et des minorités ethniques à l’école française de 1947 à 1977. In it, he refers to “le débat sur le ‘mythe’ du refus des écoles franco-catholiques d’accepter les immigrants en identifiant le décalage qui existe entre les politiques inclusives de la CECM et les pratiques d’exclusion observées sur le terrain scolaire” during those years.

Andrade found, as I did, that there was a disparity between what the CECM commissioners were trying to do — encourage more immigrants to go to French schools — and what was actually happening on the ground, the “pratiques d’exclusion observées sur le terrain scolaire.” Namely, immigrant kids were being rejected as a result of decisions being made at the school level, likely by numerous French school principals.

It was not a myth — I know from direct family history that it actually happened during those years, and it happened a lot.

The most galling story I heard was from an Italian friend of my age. His mom enrolled him in a French school in Grade 1. Apparently by mistake, he was accepted. On his first day of class, the teacher noticed him and reported him to the principal, who promptly visited the class, took my friend by the hand and marched him across the street to the English school. And so my friend, like me, grew up learning English as a primary language.

This rejection of Italians had a domino effect. Once the first born was enrolled in the English system (by choice or otherwise), the younger siblings that were to come along later usually followed into the same English system. So, even if 10 or 15 years later Italians were no longer rejected by the French system, by now those kids were simply following their older siblings’ path in English system.

For me, it all came back to life recently with the Quebec Soccer Federation’s treatment of young turban-wearing Sikh players, on the basis of “safety concerns” over the turbans. In the Sikhs’ case, the safety argument was so weak that it was quietly abandoned, leaving bare only the discriminatory reality that lay behind it.

I’ve never personally met a Sikh, but now, in my mind, they are cousins of Italians. The bias that 50 years ago was directed at Italians was now being directed at a new group of immigrants.

Italians completely understand the francophone community’s desire to preserve and promote its language and culture. After all, against all odds, we Italians are trying to do the same with ours.

But coercion can only go so far. Perhaps the use of more positive approaches would yield superior and more lasting results?

As our provincial government prepares to lay yet another layer of “social engineering” upon us with this proposed new “Charter of Values,” I hope they will consider how 50 years ago, some francophones alienated so many Italians that the outcome now 50 years later does not appear to have worked in the favour of anyone in the francophone community.

Sabino Grassi is president of EPIC Quebec, a Montreal property-management firm. He is also a board member of Casa d’Italia, the cultural hub of the Montreal Italian community that opened in Little Italy in 1936.

© Copyright (c) The Montreal Gazette