April 14, 2016: A group of Canadian Sikhs remains determined to link a massacre of almost 3,000 Sikhs in India with its campaign to encourage members of their religion to show compassion and give blood.

Sikh Nation members have no intention to disconnect their plea for blood donors from their denunciations of the Indian government for an anti-Sikh rampage in 1984 that organizers call a “genocide.”

“It’s important to remember the victims of 1984 and make sure this never happens again,” said Tera Singh, a leader of the B.C. branch of the Sikh Nation Blood Drive.

The blood donor campaign “is a very good avenue to remember the victims of genocide in a positive way,” Singh said. “It saves lives rather than kills people.”

Some Sikhs, however, believe political aspects of the blood drive divides Canada’s Sikh population of about 500,000.

The 1984 riots have long been the centre of religious controversy for the Indian government and also led to disagreement among federal Liberals.

Even though many mainstream and Indo-Canadian media outlets have reported neutrally or positively on Sikh Nation’s blood campaign, other Canadian outlets have quoted Sikhs who criticize linking an act of charity with a violent episode in the past of India.

Those critics worry the blood-donor campaign unnecessarily raises tensions about events that have become intertwined with the militant Khalistan separatist movement and the 1985 bombing of Air India Flight 182, which murdered more than 329 people, mostly Canadians, who were travelling from Canada.

Despite the friction, the Sikh Nation’s donor campaign has been fully endorsed by Canadian Blood Services. Spokesman Marcelo Dominquez says Sikh Nation has become its largest community collaborator in B.C.

Sikh Nation’s donor effort was launched more than a decade ago in light of studies released by Blood Services and others that show South Asians make up one of the large visible-minority groups in Canada that give significantly less blood per capita than non-visible minority Canadians.

Sikh Nation ads and posters refer to the blood drive as “The Campaign Against Genocide.”

Some ads for the campaign include images of splattered blood over the word “genocide.” Sikh Nation websites also include gory descriptions of the way that Hindu and other rioters murdered and raped Sikhs during the four-day massacre.

International human rights specialists acknowledge the anti-Sikh rampage that immediately followed the 1984 assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards was a pogrom, since it targeted a specific religious group.

But not many agree the attacks can technically be called genocide, a word that has come to be defined as the intent to systematically eliminate an ethnic, religious or other group.

Nevertheless, the Akal Takht, a top governing body of Sikhism, considers the killings a genocide.

And so does B.C. Liberal MP Sukh Dhaliwal, who has long called on the federal government to officially recognize the riots as such.

Former Liberal Party leader Michael Ignatieff is among those who have criticized activist Sikhs who are pushing for India, Canada and other nations to declare the 1984 sectarian violence a genocide.

“I will never stand with those who seek to polarize communities, or aggravate the tensions around long-standing conflicts that divided us in other lands,” Ignatieff said in 2010.

Bhupinder Hundal, a Vancouver journalist who until recently advised the Sikh Nation on public relations, acknowledged there is disagreement among Canadian Sikhs over how to best deal with the anti-Sikh riots in India.

“I understand both sides of the issue. The politics of it is very complex. But you can’t escape that thousands of people were massacred. And this way (through the blood drive) people are bringing a larger good out of a very troublesome period of history.”

Hundal, director of Crossnet Media Consulting Inc., declined to comment when asked what he thought about the campaign’s emphasis on the word “genocide.”

Other Sikhs were also reluctant to publicly air their views.

The Vancouver Sun interviewed three Sikhs who are normally comfortable being quoted on Canada’s Sikh population, but none would go on the record about their disagreement with the blood drive’s sectarian marketing strategy.

For his part, Sukh Dhaliwal, a B.C. businessman who was re-elected Liberal MP for Newton-North Delta in the 2014 election, initially said in a correspondence with The Sun that he would be pleased to speak about the blood drive.

But several followup attempts to interview Dhaliwal went unanswered.

The Sikh Nation’s annual blood drive occurs every November in B.C. and other regions of Canada and elsewhere.

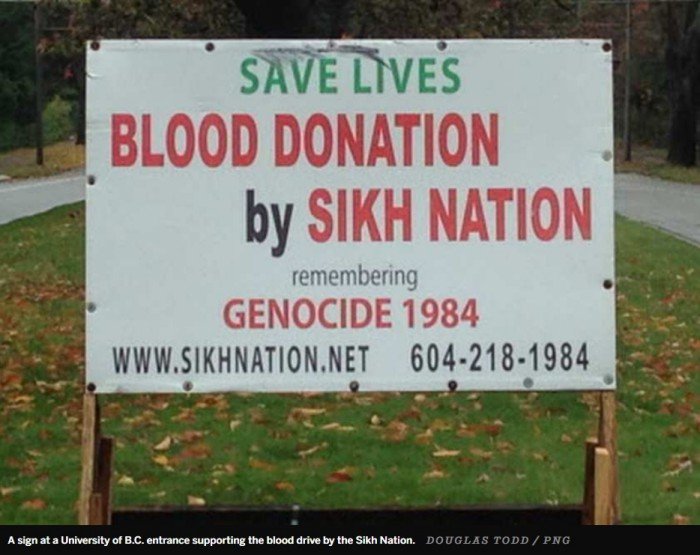

Each fall signs are posted throughout Metro Vancouver saying such things as: “Blood donation by Sikh Nation / Remember Genocide 1984.”

The signs are erected annually at the main University Boulevard gates of the University of B.C. (The deputy manager for the University Endowment Lands, Steve Butt, said the signs are posted on the boulevard without Endowment approval.)

Canadian Blood Services says the Sikh Nation campaign has in recent years provided an average of 1,346 units of blood annually in B.C. — or just over one per cent of the provincial total of 124,000 units.

Canadian Blood Services reported earlier that visible-minority Canadians give significantly less blood per capita than whites.

At a national level, Chinese Canadians represent 3.8 per cent of Canada’s population and South Asians 3.7 per cent. But CBS reported each group makes up only one per cent of the country’s blood donor base. In B.C., Sikhs make up almost five per cent of the population.

Even though Sikh Nation’s Tera Singh acknowledged Canadian Sikhs have a range of viewpoints on Sikh separatism, politics and the Air India bombing of 1985, he denied that Canada’s Sikhs are being split by the blood drive’s emphasis on the 1984 attacks.

Neither Singh nor Hundal believed the blood drive would attract more Sikh donors if the advertising stopped focusing on accusations of genocide.

“I don’t think so,” Hundal said. “You need an emotional driver. You need more than giving blood. To get people to do good you need an emotional attachment.”