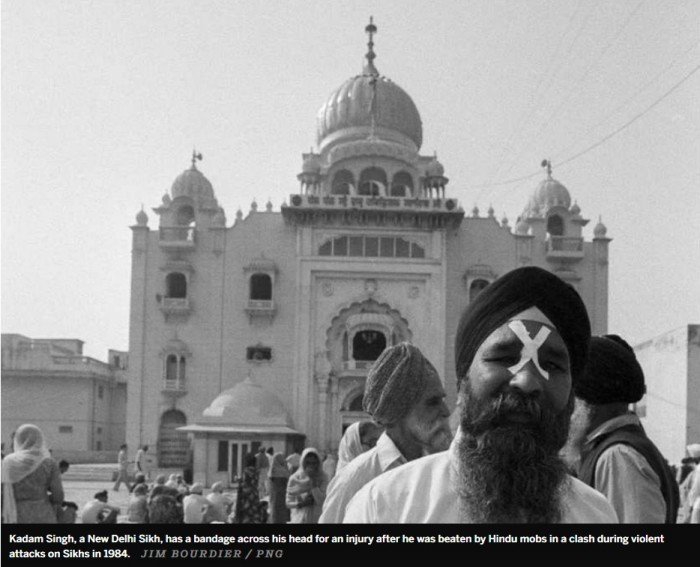

It is almost impossible to imagine the terror experienced by Sikhs in India during a four-day rampage that occurred more than three decades ago.

April 23, 2016: The evil exploded after Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s Sikh bodyguards assassinated her on Oct. 31, 1984, in retaliation for her government’s crackdown against Sikh separatists fighting for an independent homeland called Khalistan.

I can barely imagine the horror at realizing one’s own ethno-religious group had been suddenly targeted by revenge-seeking mobs, including Hindus supported by police and officials of Gandhi’s ruling party. The rioters were intent on killing, torturing, setting alight or raping innocent people in Delhi and elsewhere, simply because they were Sikh.

The 1984 massacre, which some Sikhs call a “genocide,” remains an emotional event for some of Canada’s 500,000 Sikhs, about half of whom live in British Columbia.

Activist Sikhs seek a fuller sense of truth, reconciliation and compensation. Each year Sikh Nation cites the massacre to convince thousands to donate to Canadian Blood Services. Dramatic online ads and posters refer to the blood-donor drive as “The Campaign Against Genocide, 1984.”

Some prominent Canadian Sikhs, including Surrey Liberal MP Sukh Dhaliwal, have been among those who have tried to convince the Canadian government to call the 1984 slaughter a genocide.

But is the term accurate? Or an exaggeration?

Many Canadian Sikhs feel the 1984 riot’s sectarian wounds have largely healed, including between Hindus and Sikhs. They don’t want to keep returning to separatist events that have become intertwined with the 1985 bombing of Air India Flight 182, which murdered more than 329 people, mostly Indo-Canadians. This sign at the main University of B.C. supports the Sikh Nations' blood drive. The donor campaign is done in the name of remembering the 1984 Sikh "genocide" in India, in which thousands of Sikhs were massacred. But was it a "genocide?"

This sign at the University of B.C. supports the Sikh Nations’ blood drive. The campaign is in the name of the 1984 Sikh “genocide” in India, in which thousands of Sikhs were massacred. But was it a “genocide?”

The Indian government, which up until recently was led by a Sikh prime minister, has also acknowledged almost 3,000 people were killed during the four days of mayhem. Indian officials have held inquiries, jailed hundreds of rioters and expressed grave sorrow.

The Indian government, which up until recently was led by a Sikh prime minister, has also acknowledged almost 3,000 people were killed during the four days of mayhem. Indian officials have held inquiries, jailed hundreds of rioters and expressed grave sorrow.

But some Sikh activists believe the death toll was much higher than 3,000. And they point to how Human Rights Watch, for example, maintains the Indian government has not gone far enough to right the past wrong.

That’s part of the reason the activists insist the slaughter be called genocide.

If it were, it would have tremendous legal, economic and political consequences. Governments would be forced to act further.

The debate over whether the anti-Sikh riots was genocide should be familiar to Canadians. It echoes disagreement over whether the country’s aboriginal residential-school system amounted to “cultural genocide,” an even more murky term, a term with no legal standing.

At least genocide has been defined by the United Nations, even while it remains widely disputed. No wonder it’s being referred to as the “G-word.”

Sikh blood drive hinges on ‘genocide’

The discussion over India’s 1984 massacre became heated in the comments reacting to my April 9 column, headlined, “Sikh blood drive in Canada hinges on 1984 massacre in India.”

In response to quoting sources who question whether the riot was genocide, some readers accused The Vancouver Sun of “not telling the truth,” “trying to make quick bucks,” “stirring up communalism” and denying that Sikhs in 1984 were treated the same way Hitler treated Jews during the Holocaust.

The Sun was also charged with being “racist,” a term as loaded as genocide. As Metro Vancouverites have experienced in regards to the debate over the influence of wealthy migrants on the city’s housing prices, “racist” is sometimes used by vested interests (such as real estate developers and politicians) to silence critics.

I can fully understand why some Sikhs feel their ethno-religious group underwent a savagely brutal experience in 1984, which reverberated among the world’s 27 million Sikhs. Calling it genocide attracts attention to how vile it was.

But the definition of genocide is complex.

And there are more accurate terms that still convey it was a mass trauma.

There is an additional concern: Does applying the word genocide to the persecution of Sikhs in 1984 do a disservice to those killed in larger catastrophes that the Canadian government, among others, have officially declared genocides?

There is an additional concern: Does applying the word genocide to the persecution of Sikhs in 1984 do a disservice to those killed in larger catastrophes that the Canadian government, among others, have officially declared genocides?

Canada officially recognizes the following events as genocides: The Holocaust, in which up to six million Jews were exterminated; the Holomodar, in which the Soviet Union starved to death up to five million Ukrainians; the Rwandan murder of more than one million Hutus; Turkey’s extermination of more than one million Armenians; and Cambodian leader Pol Pot’s slaughter of more than two million.

The most recent international discussion is over whether the so-called Islamic State’s ongoing slaughter of Christian minorities in the Middle East is genocide, with the U.S. among those arguing it is.

Genocide versus pogrom

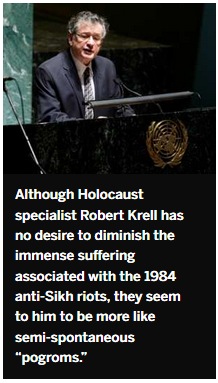

Robert Krell, a UBC professor emeritus of psychiatry who founded Vancouver’s Holocaust Education Centre, says his organization each year teaches thousands of students about the Holocaust and other formally recognized genocides.

Genocides are concerted efforts that take place over months or years, Krell said, to “exterminate a certain group of people entirely from a region.” In the case of the Holocaust, Krell said, roughly nine of 10 Jewish children were wiped out in areas occupied by the Nazis.

Although Krell has no desire to diminish the immense suffering associated with the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, they seem to him to be more like the semi-spontaneous “pogroms” launched in the past against Jews in Russia and elsewhere.

Pogroms, some of which killed tens of thousands of Jews, are characterized by sudden frenzied hatred, inflammatory rhetoric and complicity by local police, said Krell, who lost most of his relatives to Nazi concentration camps. The fact pogroms end after the frenzy dies down, he said, indicates they are not systematic genocides.

Even though some Sikh militants and politicians in India, and elsewhere, insist the 1984 riots were genocide, U.S. President Barack Obama is another who refrains from declaring them as such, instead calling them a “grave human rights violation.”

Former Liberal party leader Michael Ignatieff has also accused Sikhs who press for 1984 to be labelled genocide of being divisive and polarizing. That may be why Dhaliwal, who was re-elected in 2015, has taken in recent years to calling the riots a “pogrom.”

McGill University law professor Payam Akhavan, a war crimes prosecutor, is among those who believe it’s counter-productive for justice activists and the “human-rights industry” to so often insist on using the “debatable” terms genocide and cultural genocide.

The more important goal, says Akhavan, a member of the persecuted Baha’i faith, is to recognize the immense suffering that occurs when people are victims of what he and others prefer to call “crimes against humanity.”

The ultimate goal is not to insist on using loaded words, but to stop further persecution. To that end Sikh activists may be justified in continuing to press the Indian government for greater justice for 1984.

But they would reduce the divisive politics if they could do so by calling the anti-Sikhs riots a more precise term.

That way they would also be encouraging more people to learn about what happened.