Celestial Glory : The Kalp Vriksh - Gurudwara Kalp Vriksh Sahib at Attari, Ropar (see slide below)

###

LET NATURE BE YOUR TEACHER

And hark! how blithe the throstle sings!

He, too, is no mean preacher:

Come forth into the light of things,

Let Nature be your teacher.

She has a world of ready wealth,

Our minds and hearts to bless--

Spontaneous wisdom breathed by health,

Truth breathed by cheerfulness.

One impulse from a vernal wood

ay teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:--

We murder to dissect.

Enough of Science and of Art;

Close up those barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with yo a heart

That watches and receives.

( By -William Wordsworth )

###

“The care of the Earth is our most ancient and most worthy,

and after all our most pleasing responsibility.

To cherish what remains of it and

to foster its renewal is our only hope.”

~ Wendell Berry

###

Tree worship (dendrolatry = dendro - tree and latry - worship) refers to the tendency of many societies throughout history to worship or otherwise mythologize trees. Trees have played an important role in many of the world's mythologies and religions, and have been given deep and sacred meanings throughout the ages. Human beings, observing the growth and death of trees, the elasticity of their branches, the sensitivity and the annual decay and revival of their foliage, see them as powerful symbols of growth, decay and resurrection. The most ancient cross-cultural symbolic representation of the universe's construction is the world tree.

The image of the Tree of life is also a favourite in many mythologies. Various forms of trees of life also appear in folklore, culture and fiction, often relating to immortality or fertility. These often hold cultural and religious significance to the peoples for whom they appear. For them, it may also strongly be connected with the motif of the world tree.

Other examples of trees featured in mythology are the Banyan and the Peepal (Ficus religiosa) trees in Hinduism, and the modern tradition of the Christmas Tree in Germanic mythology, the Tree of Knowledge of Judaism and Christianity, and the Bodhi tree in Buddhism. In folk religion and folklore, trees are often said to be the homes of tree spirits. Historical Druidism as well as Germanic paganism appear to have involved cultic practice in sacred groves, especially the oak. The term druid itself possibly derives from the Celtic word for oak.

Trees are a necessary attribute of the archetypical locus amoenus in all cultures. Already the Egyptian Book of the Dead mentions sycomores as part of the scenery where the soul of the deceased finds blissful repose. - Source

| Deep Roots, Broad Branches by Purva Grover & Ramesh Vinayak Source | |

|

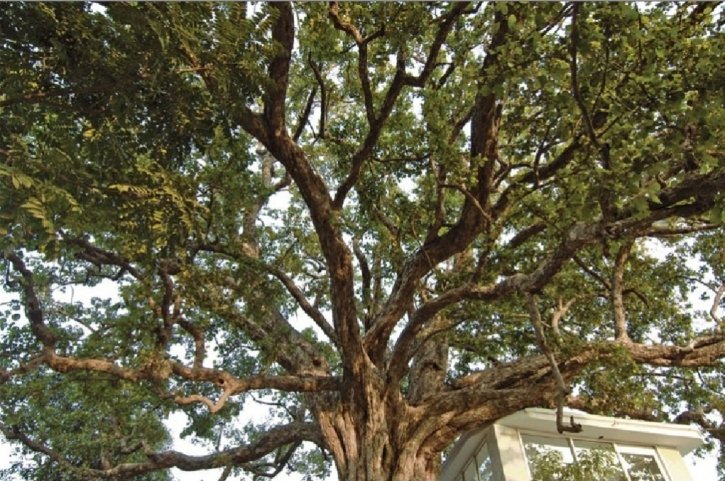

"My God has breathed His light into the dust and so brought the world into being. It is He who created the sky, the earth, the waters, and all vegetation," reads a verse in Guru Granth Sahib where Guru Nanak sings of his love for Nature. It is a universally known truth that Guru Nanak perceived a divine manifestation in every aspect of Nature. On their far-flung travels to spread the good word, the Sikh Gurus continued with this message over a span of two centuries, and also found respite in trees wherever they went to conduct their religious discourses - meditating or resting beneath them, for example. Long after they left, the trees were marked and remembered for their association with the visiting Gurus and often commemorated alongside the respective shrines that sprang up in memory of their sojourns. For some time now, Damanbir Singh Jaspal, a Punjab-cadre senior Indian Administrative Service officer, has been studying the link between the ancient trees across the land and the Gurus. "The idea was to explore the roots of our Sikh heritage and its repeated tryst with trees and Nature. In fact, a lot of people do not even know that some of our most revered gurdwaras are named after trees," says the seasoned bureaucrat. Damanbir Singh's duties as Principal Secretary, Information, Public Relations & Financial Commissioner (Forests) - for the Government of Punjab - has helped him find fodder for his exercise. "Be it in the form of a meditation aid or a source of nourishment for Man or horse (e.g., jand leaves), or a source of timber (tahli), trees have always figured prominently in the Sikh Faith," he says. To establish this link, Damanbir has traveled across the State of Punjab and beyond, with his Nikon camera and captured on film 17 different species that have 48 of the most historical Sikh shrines named after them. His completed documentation, now compiled into a book called Tryst with Trees: Punjab's Sacred Heritage, includes photographs and descriptions of the gurdwaras, and a write-up on the botanical features of each tree and its link with the shrine. "While my travels helped me understand the history behind the old trees, it was my meeting with the people associated with the gurdwaras that made my mission most interesting and rewarding," he explains. The president of the Neem Sahib gurdwara in the Akar village of Patiala related to Damanbir an incident wherein the great Maharaja Ranjit Singh bowed in reverence before a frail old man reputed to be close to being a centenarian - only because the latter had once actually seen Guru Gobind Singh! "And to think that today, the 400-year old neem tree at this gurdwara is the only living creature that has seen the Guru!" exclaimed the gurdwara administrator. Traveling over 20,000 km over the course of his research, Damanbir's study has mostly been confined to Punjab. But a captivating document from outside the State is that of a lone neem tree in Leh (in Himalayan Ladakh). Legend has it that it sprouted from a daatan (sprig) planted by Guru Nanak in 1517, after he finished brushing his teeth with it. Damanbir's major concern now is the real threat that some of these historical trees face from builders and renovators of gurdwaras. For instance, the Tahli at the Santokhsar gurdwara near the Durbar Sahib and associated with Ram Das, the Fourth Guru and the Founder of Amritsar, was cut recently down to make way for a new, large marble-clad building. Then, the tamarind tree at Imli Sahib gurdwara at Chamkaur Sahib was put to the axe in 2005 by the karseva jathaa in order to erect a new structure in its place. "People must create awareness about these historical trees or coming generations will remember these shrines not by their trees, but by the marble," states Damanbir. Still, there's hope in the form of the 450-year-old tahli tree at Gurdwara Tahli Sahib, Nawanshahar. Damanbir points to a picture of a tree branching out through three holes punctured through the ceiling of the gurdwara, and says: "The management created a new building there without causing any damage to the tree." Incidentally, Damanbir Singh Jaspal is also President of an NGO called Chandigarh Nature and Health Society, which has undertaken the task of preserving these trees of sacred memory through modern technology. The project titled "Clonal Propagation of Selected Sacred Species" has, by means of an experiment, obtained stems of four of the most important trees associated with historical gurdwaras: the Dukh Bhanjani Beri, Baba Buddha Beri, and Lachi Ner Beri (all located on the precincts of the Durbar Sahib in Amritsar), and the tree at Gurdwara Ber Sahib in Sultanpur Lodhi. Call it a small step in tissue-culture, but certainly a giant leap for the preservation of our rich heritage! [Courtesy: Simply Punjabi] Photos by Damanbir Singh Jaspal - Top of this Page: Ber Baba Buddha ji, Durbar Sahib, Amritsar. Bottom photo: Gurdwara Luhura Sahib, Lahore, Pakistan. Second from bottom: Gurdwara Kalp Vriksh, Ropar. Third from bottom: Gurdwara Tahli Sahib, Hoshiarpur. |

|

"Tryst with Trees: Punjab's Sacred Heritage"

by Damanbir Singh Jaspal

Related Article:

Sikhism is eco-friendly

By Prabhjyot Singh

Source

The uniqueness of identifying gurdwaras with common Punjabi trees is unprecedented. Even the Gurbani refers to various species of trees, which are useful to mankind.

"Sikhism is not only one of the most modern and scientific religions but is also environment friendly," says Mr Damanbir Singh Jaspal, an IAS officer of the 1976 batch, who has just completed his research, documenting 48 historic Sikh shrines that are commemorated by the names of 17 native species of trees.

This uniqueness of identifying its most sacred places of worship with common trees is unprecedented. Perhaps no other religion has given importance to vegetation the way Sikhism has.

If trees and forests were the centre for meditation and communion with the Creator for the first five Sikh Gurus, they provided security, shelter and sustenance for the last five Gurus who spent most of their time in the jungles, fighting the Muslims.

Says Mr Jaspal: "The profusion of allusions and references to trees, nature and environment in Guru Granth Sahib and the commemoration of scared shrines by popular species of trees can be explained by the vigorous outdoor life and travels of the Sikh Gurus, who were probably the most mobile among all religious preachers of the world."

Even the Gurbani refers to various species of trees, eulogising species, which are useful to mankind. The Gurus inferred that it is not the girth, size, or beautiful flowers that determine the significance of a tree but it is its usefulness that makes it important for mankind. That may perhaps be the reason that "Simbal", a huge tree with big attractive colourful flowers, did not find favour with them.

"Simbal rukh saraira,

att deeragh att much,

Oye je awae aas kar,

Jaye nirase kit,

Fal fikke ful bakbake,

Kum na awae patt,

Mithat neevein Nanaka,

Gun changayian tatt."

This sloka from the Gurbani says that though the tree of Simbal is a huge tree and has big colourful flowers that attract birds, they go back disappointed as the flowers lack nectar. Even the leaves of the tree are of no use. It is not the huge size but humbleness that marks usefulness.

Of the 17 species of trees researched by Mr Jaspal during his six-month long project, he found that since zizyphus jube has sweet fruit; Jand (prospis spicigera) has leaves that are used for feeding horses; Neem (margassa) has medicinal value; Tahli (shisham, state tree of Punjab) has wood; Imli (tamarind) has both food and medicinal value; they found favour with the Sikh Gurus.

The trees that have sanctity in Sikhism include Bohr (Ficus bengalensis), Pipli (Ficus religiosa), Jand (Prosopis spicigera), Garna (Capparis horrida), Karir (Capparis aaphylla), Phalahi (Acacia modeta), Reru (Mimasa leucophloea), Luhura (Cordia latifolia), Tahli (Shisham), Imli (Tamarind), Amb (Mangifera indica), Harian velan, Neem (margassa), Ritha (Sapindus mukorosa), Kalp (Mitragina parvifolia) and Ber (Zizyphus jujube), says Mr Jaspal.

Clusters of such useful trees were invariably the sites selected by the travelling Gurus as the halting places for shade as well as shelter. Besides these trees were also sources of nourishment for the Guru’s entourage. After the departure of the Guru from the site, the trees were remembered for their association with the Guru and were later commemorated by building shrines around them.

It is one reason why, he says, some of the trees preserved in historic shrines were older than 400 years. One such example is Gurdwara Tahli Sahib in Garhshankar in Nawanshahr.

Dr Jaspal’s research took him to Leh where Guru Nanak had gone during his second of the four Udasis. The local legend in Leh has it that Datun (Margossa) sprouted from a datunplanted by Guru Nanak. The tree is greatly revered by Muslims and Buddhists alike for its sanctity, adds Mr Jaspal.

Though Mr Jaspal plans to write a book soon, he has decided to hold exhibitions of the photographs of these 48 historic shrines featuring the 17 species of trees. The entire project has been sponsored by the WWF.

Says he: "It was interesting as it not only took me to all historic Sikh shrines but provided me with an insight into how scientific Sikh Gurus were. The world started talking about environment and ecological balance only during the past three to four decades while the Gurus realised their significance more than 500 years ago. In the same manner, the world has realised how dangerous smoking is for human beings. And the Gurus had prohibited their disciples from smoking."

Mr Jaspal has now decided to pursue his interest further through his Chandigarh Nature and Health Society, an NGO which has obtained stems of four of the most sacred trees associated with the Sikh shrines, namely beri of Dukh Bhanjani Beri of Sri Harmandir Sahib, Beri of Baba Budha (also of Sri Harmandir Sahib), Beri of Gurdwara Ber Sahib of Sultanpur Lodhi and Beri of Lachi Ber of Sri Harmandir Sahib.

Inducement of rooting in these stems is now being attempted in simulated environment through a mist chamber, shade house, growth hormones to promote rooting, adds Mr Jaspal, hoping that "propagation of these historic trees will generate awareness and respect for nature in general and environment in particular.

--------------------------------------

Related Articles:

Related Articles:

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/historic-gurdwaras-and-trees-pay-price-modernisation

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/sikh-gurduaras-societies-federal-territory-malaysia-and-sikh-determination

The Religious Roots Of Trees

Religion News Service | By Lisa Schencker

Source

SALT LAKE CITY (RNS) Whether churchgoers realize it or not, the trees in their churchyards have religious roots.

Those tall, thin-branched trees on the corner of this city's Episcopal Church Center of Utah, Purple Robe Black Locusts, were probably named after a biblical reference to John the Baptist eating locusts and honey.

Nearby, the crab apple tree just outside the Episcopal Cathedral Church of St. Mark produces a small, sour fruit used by 15th-century monks to treat diarrhea, dysentery and gallstones.

And the flowers of a nearby dogwood tend to bloom around Easter.

"My hope," said University of Utah biology professor Nalini Nadkarni, "is (worshippers) will realize that nature and trees are as much a part of their sacred ground and worthy of reverence as what goes on inside a cathedral or church." .....more