Debunking Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin and the False Allegations Against Guru Tegh Bahadur Sahib Ji

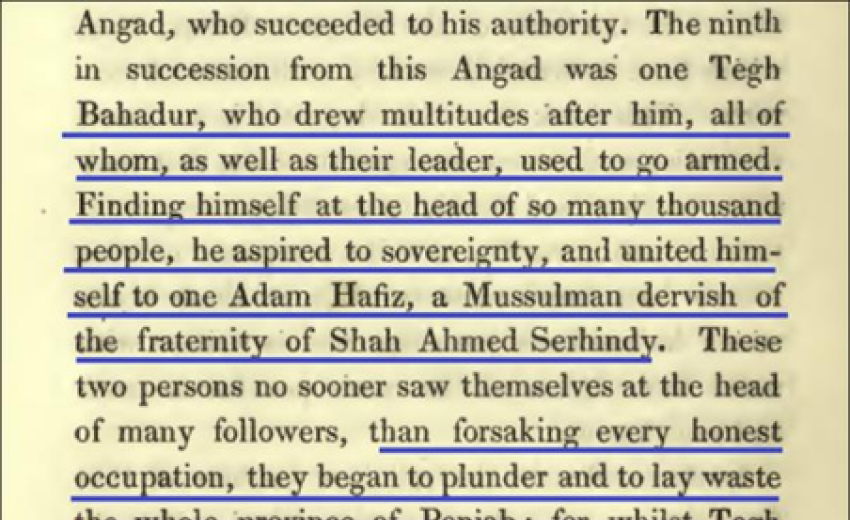

This article examines the credibility of Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin, authored by Sayyid Ghulam Husain Tabatabai, with specific reference to its portrayal of Sikh history. Written nearly a century after the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur, the work contains serious allegations against the Guru and Hafiz Adam, a disciple of Ahmad Sirhindi, accusing them of raising armed followers and plundering the country. The purpose of this article is to critically assess these claims through chronological analysis, comparison with contemporary non Sikh sources, and evaluation of internal inconsistencies, in order to determine whether Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin can be regarded as a reliable historical source for Sikh history.

H. R. Gupta offers a useful contextual explanation for Sayid Ghullam Hussain’s hostility toward the Sikhs. By the late eighteenth century, Sikh power had expanded significantly across northern India. In June 1781, Najaf Khan, then prime minister of the Mughal

Empire, formally recognized the Sikhs’ right to collect Rakhi at 12.5 percent of the standard land revenue in Haryana and the Upper Ganga Doab (present-day western Uttar Pradesh). Sikh authorities also collected Rakhi from territories of the Nawab of Oudh across the Ganga in central Uttar Pradesh.

Given these developments, it is hardly surprising that Ghulam Husain had little sympathy for the Sikhs or their Gurus. His writings consistently reflect resentment toward their growing political and social influence.

The present discussion seeks to highlight not only Sayid Ghullam Hussain’s partiality but also the numerous errors and internal contradictions that weaken his historical credibility. His first and most fundamental mistake was the false association of Guru Tegh Bahadur with Hafiz Adam, a follower of Ahmad Sirhindi.

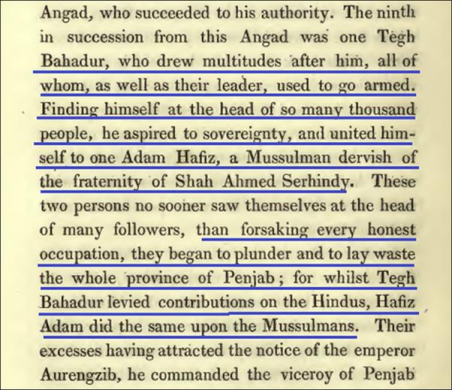

Historically, Ahmad Sirhindi was a staunch proponent of Islamic orthodoxy and expressed overt hostility toward the Sikh tradition. Contemporary evidence shows that he openly celebrated the execution of Guru Arjan Dev under Jahangir, viewing it as a triumph over what he considered heresy. His writings reveal a desire for the complete eradication of the Sikh community—an outlook fundamentally incompatible with any alleged cooperation between his dervish and a Sikh Guru.

This stark ideological incompatibility further exposes the implausibility of Sayid Ghullam Hussain’s narrative and reinforces the conclusion that his account was shaped less by historical evidence than by sectarian bias and political resentment.

It is difficult to conceive that Hafiz Adam, a devoted follower of Ahmad Sirhindi, would have collaborated with the leader of a religious community toward which his master was openly hostile—so much so that Sirhindi advocated the complete eradication of that sect. Such an association would be fundamentally inconsistent with both theological allegiance and historical context.

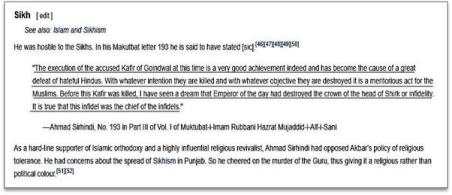

A closer examination of Sayid Ghullam Hussain’s personal predispositions helps clarify why he constructed this improbable linkage between the Guru and Hafiz Adam, a dervish associated with Ahmad Sirhindi. Sayid Ghullam Hussain was himself a Shia Muslim, and his writings reveal a marked inclination to exalt Shia political figures. This tendency has been explicitly noted by scholars as a significant weakness in his work.

In this light, the association appears less the result of historical evidence and more a product of sectarian bias—one that led Sayid Ghullam Hussain to diminish figures aligned with anti-Shia traditions by attributing to them actions and associations unsupported by contemporary sources.

The allegations directed against the dervish associated with Ahmad Sirhindi appear to stem from Sirhindi’s well-documented anti-Shia theological position. Sirhindi openly criticized Shia doctrines, justified the execution of Shia figures, and portrayed the sect as deviating from what he regarded as orthodox Islam.

In this context, it appears that Sayid Ghullam Hussain attempted to diminish the stature of the so-called “anti-Shia Sirhindi tradition” by falsely associating Sirhindi’s dervish with acts of looting and criminality—an allegation that finds no support in contemporary records from the reign of Aurangzeb. The complete absence of such accusations in primary sources strongly suggests that this portrayal is a later fabrication rather than a historically grounded claim.

Moreover, Sayid Ghullam Hussain demonstrates a broader pattern of personal and ideological bias in his writings. One notable example is his hostile depiction of Nawab Sirajuddaulah, despite evidence that the Nawab had treated him with considerable favor. This tendency to distort the reputations of individuals based on personal or sectarian predispositions further undermines the credibility of his historical assessments.

Therefore, it is evident that the author of Siyar-ul-Mukhatein used to carry a personal bias against his subjects, just like in the case of Nawab Sirajdaullah and Ahmad Sirhindi. He used to margrave his targets and associate them with charges that were never true which were made just to diminish the status of the target. He did the same with the Sikhs, because the Sikhs had become the masters of Punjab, and the Nawab had to pay tribute to them, which was obviously irking him as a proud Muslim.

In addition to baseless allegations, Ghulam Husain made a grave error here by bracketing Guru Tegh Bahadur Sahib with Hafiz Adam. Hafiz Adam was banished by Shah Jahan in 1642, thirty-three years earlier. Hafiz went on a pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina where he died in 1643. Dr Ganda Singh in 1977 quoted several works (with page numbers) to prove the discrepancy of the year by Ghulam Husain and fallacy of his allegations.

• Kamal-ud-din Ahsan, Rauzat-ul-Qayumia, 178

• Nazir Ahmad, Tazkirat-ul-Abidin, 124-25

• Mirat-e-Jahan Nama 606

• Ghulam Nabi, Mirat-ul-Qwanin, 417

• Mirza Muhammad Akhtari. Tazkirah-e-Hind-o-Pakistan, 401

• Abdul Hayee Hasani Rai-Bareilvi, Nazzat-ul-Khwatir, vol. 5, pp. 1-2

Rauzat-ul-Qayumia is a credible source for studying the life and milieu of Ahmad Sirhindi and his circle, as its author was closely connected to the Mujahid family. The author records that Hafiz Adam was banished by Shah Jahan in 1642. Owing to the author’s direct association with the Sufi tradition, his testimony carries particular weight when discussing figures within Ahmad Sirhindi’s spiritual lineage, and his account merits serious consideration.

Even if certain modern writers regard Rauzat-ul-Qayumia as exaggerated in parts, at least five additional independent sources concur that Hafiz Adam died in 1643. While isolated sources may be biased or mistaken, it is methodologically untenable to dismiss six convergent accounts in favor of a single contradictory narrative. Historical reasoning does not operate on such selective acceptance of evidence.

By contrast, Siyar-ul-Mukhatein alone associates Hafiz Adam with Guru Tegh Bahadur without citing any contemporary authority. This unsupported linkage reflects not only bias but also a fundamental lack of chronological awareness. The narrative appears to have been constructed retrospectively, likely to justify the execution of a non-Muslim religious figure and to malign individuals perceived as doctrinally inconvenient.

It is therefore a well-established fact that Hafiz Adam died in 1643—approximately thirty two years before the execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur. Anyone seeking to challenge this conclusion must produce contemporary evidence demonstrating that Hafiz Adam, the dervish associated with Ahmad Sirhindi, ever interacted with or collaborated with the Guru.

Before examining additional contemporary Persian accounts, it is necessary to highlight further errors committed by Siyar-ul-Mukhatein in its treatment of Sikh history. Beyond its evident prejudice against the Sikhs, the work is riddled with factual inaccuracies. These errors collectively demonstrate why Siyar-ul-Mukhatein cannot be regarded as a reliable historical source on Sikh history.

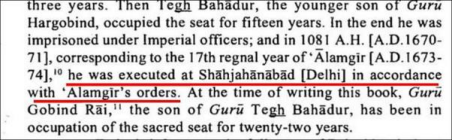

1. Place of Execution

Sayyid Ghullam Hussain’s first major error lies in associating the already deceased Hafiz Adam with Guru Tegh Bahadur. More strikingly, he claims that the Guru’s execution took place in Gwalior, a statement that does not withstand historical scrutiny. Contemporary

Persian sources unanimously place the execution in Delhi, rendering this assertion demonstrably false.

Allegations Against Guru Tegh Bahadur Sahib Ji

Even the unlettered populace of the period was aware that the execution took place in Delhi, not Gwalior. It is therefore puzzling that Sayyid Ghullam Hussain identified Gwalior as the site of execution. Contemporary Persian sources unanimously locate the execution in Delhi.

One such source is Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh (1695), authored by Sujan Rai Bhandari. This work provides a general history of India, with its principal discussion of the Sikhs appearing

in the chapter on the province of Lahore. Sujan Rai records the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur, albeit briefly—likely to avoid incurring the displeasure of the Mughal authorities—yet he makes no error regarding the location of the execution.

That a writer could make sweeping and defamatory claims about the Guru while being unaware of the very place of his execution seriously undermines his credibility. Sayyid Ghullam Hussain neither engages with primary sources nor consults reliable historical accounts; instead, he repeatedly presents inaccurate details. His assertion that Gwalior

was the site of execution thus represents yet another demonstrable factual error. 2. The Fate of the Body after the Execution

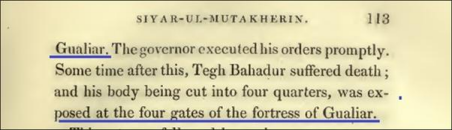

Once again, Sayyid Ghullam Hussain’s narrative collapses under scrutiny. He alleges that the Guru’s body was cut into four pieces and displayed on the gates of Gwalior—a claim entirely unsupported by contemporary evidence and directly contradicted by Sikh and Mughal-era accounts alike. This assertion further illustrates the extent to which his narrative relies on fabrication rather than verifiable historical testimony.

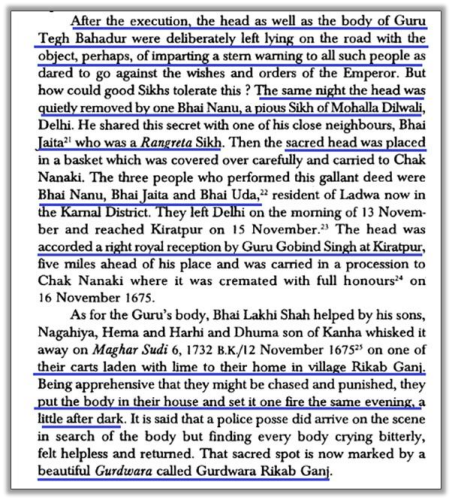

First, the execution took place in Delhi, not Gwalior. Second, the claim that the Guru’s body was disfigured is equally unfounded. This can be demonstrated through Chaupa Singh’s Rehitnama, a principal eyewitness account.

According to Chaupa Singh, following the Guru’s execution, a Sikh named Bhai Jaita courageously retrieved the Guru’s severed head, while other Sikhs disguised themselves and carried away the Guru’s body on a three-wheeled cart to cremate it in secrecy. The site of this cremation is today commemorated by Gurdwara Rakab Ganj Sahib.

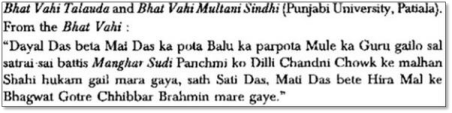

The identical sequence of events is claimed by Bhatt Vahis, another eyewitness to the occurrences. Bansavalinama (1759) reiterates the same point once again.

This once again illustrates the falsity and unreliability of the views presented in Siyar-ul Mukhatein. As a historical source on Sikh history, the work proves deeply flawed and methodologically unsound.

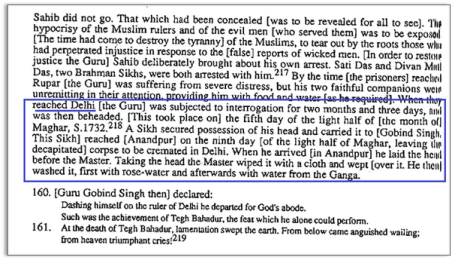

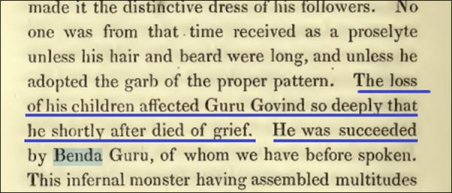

3. The Fabrication Concerning the Death of Guru Gobind Singh

Sayid Ghullam Hussain once again errs when explaining the circumstances surrounding Guru Gobind Singh’s death. He claims that the Guru died from overwhelming grief and despair following the loss of his family. This assertion is not supported by contemporary

evidence and stands in direct contradiction to reliable Mughal and non-Sikh accounts, thereby further undermining the credibility of Siyar-ul-Mukhatein as a serious historical source.

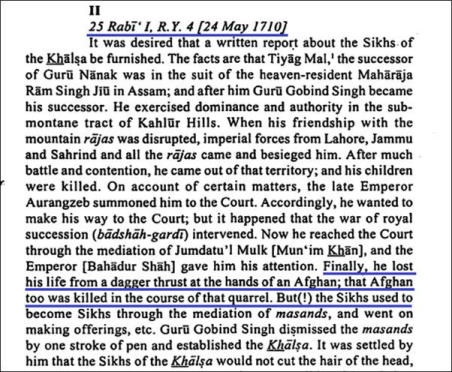

Siyar-ul-Mukhaein can once again be falsified by examining a Mughal contemporary report from the court of Bahadur Shah concerning the death of Guru Gobind Singh. This Mughal court account directly contradicts the claims advanced in Siyar-ul-Mukhaein, thereby further exposing the work’s reliance on conjecture rather than contemporary evidence.

Here, the Mughal account unequivocally states that the Afghan’s dagger caused the Guru’s death and that the Afghan himself was killed in the process.

The fact that this testimony originates from a Mughal source and is corroborated by contemporary accounts not only highlights Sayid Ghullam Hussain’s ignorance regarding Sikh affairs but also indicates his failure to consult or seriously engage with contemporary materials on the Sikhs.

In light of this, it is reasonable to conclude that Siyar-ul-Mukhatein’s narrative of Sikh history is largely constructed from rumor and conjecture rather than from credible historical evidence.

Review of the major fallacies in his work reveals the following issues:

• The false invocation of Ahmad Sarhindi, apparently motivated by his anti-Shia stance, despite its irrelevance to the subject under discussion.

• The erroneous grouping of Hafiz Adam with Guru Tegh Bahadur, which is historically untenable, as Hafiz Adam died thirty-three years prior to the Guru’s execution.

• A factual blunder in identifying Gwalior as the site of the Guru’s execution.

• Repeated inaccuracies concerning the treatment and fate of the Guru’s body following his execution.

• False and misleading claims regarding the death of Guru Gobind Singh.

• An openly hostile portrayal of Nawab Sajidaullah, unsupported by balanced historical analysis.

• The exaggeration and over-glorification of Shia political figures, reflecting sectarian bias rather than historical objectivity.

• A persistent pro-English orientation, which further compromises the neutrality and credibility of the narrative.

In light of the numerous inaccuracies identified, Siyar-ul-Mukhatein can no longer be regarded as a reliable source—at least with respect to Sikh history. The author demonstrates clear bias against the Sikh community, relies on misinformation, commits multiple factual errors, and, most critically, fails to engage seriously with contemporary sources. This methodological negligence results in a series of substantial historical blunders.

It is therefore reasonable to set aside Siyar-ul-Mukhatein as a credible historical authority on the Sikhs. I will now turn to non-Sikh contemporary sources to demonstrate that the Guru was not a plunderer, but rather a figure held in high esteem by both Muslims and Hindus.

Before proceeding, it is necessary to define the term plunderer. A plunderer is an individual who, typically during periods of war or civil unrest, forcibly seizes property from persons or places. Plundering implies the violent and unlawful acquisition of goods.

Sayid Ghullam further accuses the Guru of terrorizing the populace and wreaking havoc across the country. The following section will examine how contemporary, non-Sikh sources evaluate and respond to this claim.

Ibratnama(1718)

The contemporary Persian author Mohommad Qasim states in his book "Ibratnama" that the Guru used to receive great honor and respect from the public in along with receiving hundreds of priceless gifts.

Had the accusation of plundering been accurate, Muhammad Qasim could easily have recorded instances of the Guru forcibly seizing the property of local inhabitants, just as he explicitly did in the case of Banda Singh Bahadur. Yet no such allegations appear in his account. Instead, he notes that the Guru’s following was steadily expanding and that his stature and influence were correspondingly increasing.

This selective contrast is significant: where Muhammad Qasim perceived coercion or violence, he did not hesitate to document it. His silence regarding any such conduct by the Guru therefore strongly undermines the charge of plunder and further supports the view that the Guru’s authority rested on voluntary devotion rather than force.

How could this have been possible if he were truly a threat to the state?

Contemporary accounts state that the Guru received numerous valuable gifts from his followers as tokens of devotion and reverence; however, there is no evidence whatsoever of coercion, violence, or widespread destruction attributed to him. The claim that the Guru referred to himself as “Sacha Padshah” is incorrect—this title was conferred upon him by his followers, not self-assumed.

Moreover, if the Sikh Guru had truly been a plunderer, it is implausible that a Muslim chronicler would have fabricated praise or sought to defend him. On the contrary, Muhammad Qasim explicitly refers to the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur, a designation

that itself carries moral and spiritual legitimacy. Significantly, he associates the Guru with the fakir Sarmad, who was likewise executed by Aurangzeb for similar theological reasons. This parallel further reinforces the conclusion that the Guru’s execution stemmed from religious and ideological opposition, not from any alleged criminal conduct.

After researching the reason for the execution of Sarmad and how it is linked to Guru Teg Bahadur Ji, we got a common link, which was "heresy”.

What is heresy?

Belief or opinion contrary to orthodox religious doctrine.

Heresy is a belief or action that goes against generally accepted beliefs. It can also be defined as a belief that doesn't align with the official tenets of a religion.

In Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, heresy has sometimes been met with censure ranging from excommunication to the death penalty.

What led to the execution of Sarmad?

Aurangzeb (1658-1707) emerged victorious, killed his former adversary and ascended the imperial throne. He had Sarmad arrested and tried for heresy. Sarmad was put to death by beheading in 1661. His grave is located near the Jama Masjid in Delhi, India. The grave of Sarmad Kashani in Old Delhi Sarmad was accused and convicted of atheism and unorthodox religious practice. Aurangzeb ordered his Ulema to ask Sarmad why he repeated only "There is no God", and ordered him to recite the second part, "but Allah". To that he replied that "I am still absorbed with the negative part. Why should I tell a lie?" Thus, he sealed his death sentence.

This demonstrates once again how psychopathic and religious intolerant Aurangzeb was. Muhammad Qasim's association of Guru Teg Bahadur with Sarmad strongly suggests that Aurangzeb’s execution of the Guru was driven by opposition to the beliefs upheld within Sikh tradition, rather than by any alleged acts of looting or criminality as claimed in Siyar.

Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh (1695)

Sujan Rai Bhandari's Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh, completed in 1695, is a history of India. The main account of the Sikhs and their history is given in the chapter on the province of Lahore. He gives a detail sketch about the lifestyle of the Sikh Gurus and their followers.

His descriptions of the Sikhs are consistently positive and often laudatory, explicitly portraying the Guruship as sacred. While he records numerous details about the Sikh community and its practices, he offers no criticism of the Guru whatsoever. This omission is significant: had the Guru been a violent plunderer or morally corrupt figure, a contemporary observer would almost certainly have documented such behavior.

This absence of any adverse remark therefore constitutes further contemporary evidence of respect for the Sikhs and, importantly, of the Guru’s unimpeached moral standing.

Sujan Rai Bhandari's account informs us that the leaders of this sect are men of prayer, discoursers, and mysticism, which brings us to our next topic:

Raja Ram Singh requests the Guru to accompany him towards Assam to undo the effects of Ahom witchcrafts.

If the Guru were merely a robber, why would Raja Ram Singh of Amber request that he accompany him on his eastern campaign? When commanding one of the most powerful military forces of the time, what reason would Raja Ram Singh have to seek the presence of an ordinary plunderer on the battlefield?

The explanation is straightforward: Raja Ram Singh held the Guru in the highest esteem and regarded him as a mystic and spiritual authority capable of offering protection against the alleged witchcraft of the Ahoms. It was for this reason that the Raja sought the Guru’s refuge, and the Guru, in turn, granted it.

This again nullifies the claim of Guru being a ravager; otherwise, the Raja would have not asked him to accompany him to the east.

Conclusion

I still have numerous examples showing that Muslims and Hindus alike regarded the Guru as a saint; these will be discussed in a separate section. The primary objective of this paper was to refute Siyar-ul-Mukhatein through the use of contemporary evidence, critical reasoning, and logical analysis—an objective I believe has been successfully achieved.

The author’s personal predispositions have significantly distorted the portrayal of historical events. Consequently, narratives derived from Siyar-ul-Mukhatein lack credibility, as they rest on a fundamentally flawed foundation. This essay, therefore, aims to demonstrate the unreliability of Siyar-ul-Mukhatein as a source for Sikh history.