|

Position Paper Position Paper

Creation of the Sikh Family Center

This paper1 is designed to provide insight to the culture-change work being undertaken by

Sikh Family Center (SFC), an initiative to provide social services through an evidence-based

and empowerment-oriented approach. The development of SFC since 2009, illustrates the

propagation of a culture that neither apologizes for difference nor allows itself to be

employed as an excuse for any form of oppression.

While Sikhs' unique identities—turbans, long hair, beards—have become targets of

discrimination and even hate since 9/11, Sikhs have organized to create powerful civil

rights organizations across North America. However, as the community remains focused on

post 9/11 issues, intra-community problems often proliferate in shadows. There are few

dedicated social services avenues and while there are many gurdwaras (Sikh congregation

centers), there are few organized attempts to focus on promoting health and safety within

the Sikh home and community while being cognizant of the cultural and linguistic context.

|

The Sikh Family Center's mission is to promote healthy families in the Sikh American

community by closing current gaps in access to resources and increasing community

awareness and activism.

SFC works with volunteers, institutions, and partners within and outside the community to

facilitate community-building activities (mentoring programs, parenting classes, reading

groups) as well as to provide crucial social services (crisis intervention, medical camps), with

special attention to cultural tradition, immigration experience, and language access. |

Striving to fill a crucial gap, SFC undertakes various activities, including:

- Extensive Needs Assessment Surveys.

- Medical Camps and Clinics.

- SFC Message Line, confidential & free.

- Volunteer and Peer-Counselor Trainings.

- Educational Presentations & Trainings.

Here, we highlight 3 guiding principles that inform SFC’s development and activities.2

Principle One: Resisting Essentialism—Gender & Cultural.

Cultural essentialism conceives of members of a cultural group as bearers of a unitary

culture, which is static, and defines and distinguishes them from others.

Gender essentialism is "the notion that a unitary, 'essential' women's experience can be

isolated independently of race, class, sexual orientation, and other realities of experience."3

Rejecting both these tendencies, SFC recognizes the interplay of the below realities:

- Sikh women and men have experiences that are gendered—informed by how society perceives females and males—yet cannot only be explained through the lens of gender alone.

- The consideration of belonging to a distinct faith community itself guides choices, identity, and experience. Being Sikh, for many, is a first identity, within which many other identities operate.

- While Sikhs form a distinct community, this community itself is neither homogenous nor so alien from other communities that it only responds to 'special' services.

SFC thus recognizes the unique nature of our community while refusing to over-state challenges as unique only to (the often misunderstood) Sikh community.

For example, gender-based violence and discrimination exist in all communities,4 and the

Sikh community, as the larger the South Asian community, shows several disturbing trends

as well.5 However, different women and communities experience the violence differently,

related to their different positions in American society today as well as the different level of

services6 available to them.

SFC's aim is to continue developing culturally sensitive resources as well as to help build

trust for mainstream local institutions where help is available. One of the largest gaps in

the Sikh American community has been identified as the lack of access to existing county &

state resources—psychological, social, medical, legal services. With language,

transportation, and legal barriers, many individuals find themselves unaware of what

resources are available to them and services they may be eligible for. SFC does not

endeavor to re-create resources, rather seeks to link community members to existing ones.

|

Case Study 1

A 32 year old came to SFCs medical clinic table at a gurudwara to get more

information. She reported 2 healthy children and no medical problems. Each week, she continued

to ask a few more questions when she visited the table and spent more time getting to know the

volunteer staff. A few months later she presented with vague symptoms of a mild head ache. The

following visit she was evaluated for leg pain and then again for foot pain and back pain.

After nearly 6 months of being acquainted with SFC clinic volunteers, during one visit for

"skin problems" she pulled up the sleeves on her arms to reveal old healed burn scars on her arm,

chest and abdomen. This further opened up the discussion to her untreated PTSD, depression and

isolation anxiety. SFC referred her to her local County Department of Social Sen/ices and educated

her to reach out to call 911 if in danger or in case of an emergency. Even with Punjabi-speaking Sikh

service provides, it took several months for us to be able to establish rapport and build trust for her

to be able to talk about this. |

Principle Two: Learning From Our Community.

SFC strives to respond to documented needs, and practices an evidence-based

methodology. Recognizing how most national, regional, or statewide statistics do not

disaggregate the Asian Pacific Islander data7 and thus do not provide data specific to the

Sikh American community, SFC has continued to conduct its own needs assessment surveys

for the past two years. SFC remains committed to the ethical use of statistics collected,

including reading and utilizing them in context, and with an eye to providing future

services.

|

SFC's Needs Assessment Survey has thus far been conducted in-person at gurudwaras, community

events, and Sikh gatherings across the United States to directly understand from the community what

our priorities and areas of focus should be. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such needs

assessment of the Sikh American community, seeking reliable data on the community’s demographics,

experiences and social services needs. Any Sikh American above the age of 18 can fill a survey.

For the first set of surveys, SFC did not introduce the surveys online for a few reasons including the

lack of online access for large parts of the community: We sought to resist the tendency to turn to an

easy online tool, which would have lessened the incentive to go out and conduct surveys with

segments of the community that do not have net-connectivity. |

Our survey asks a range of questions, assessing current health and wellness of men,

women, and children in the family.

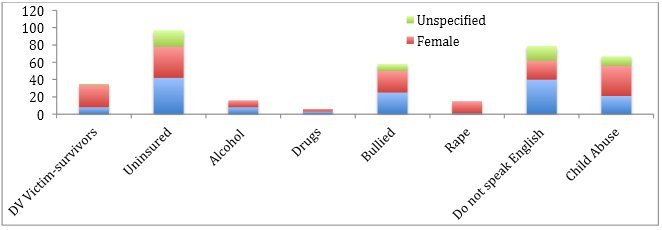

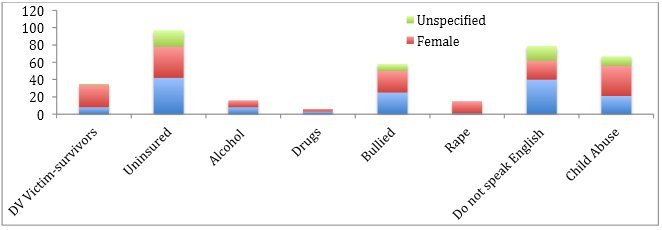

Of the 443 current respondents, from 16 states from the United States, 390 are from

California.

Gender: 43% of respondents are female, 39% male, and 18% did not specify their gender.

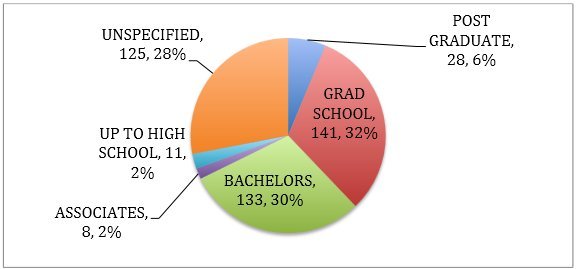

Education Level:

Children & Activities: 254 (57%) of the respondents have children, of which 75% have a

library card and 24% are active in sports.

Language Access: 18% of the respondents do not speak English and identified Punjabi as their first language.

Health Access: 22% of respondents reported having no medical insurance.

Substance Abuse: While 8 (2%) of men and 8 (2%) women identified themselves as having alcohol problems, 3 (1%) identified with drug problems.

Violence & Abuse:

- 1 (0%) male and 14 (3%) females report rape. Perpetrators were mostly male relatives.

- Overall, 35 (or 1 in 13) respondents to our national survey reported having survived family, partner or domestic violence (DV).8 8 of these 35 respondents were male, and 26 were female, with 100% male relative as the perpetrator. There is also significant increase in number of these respondents reporting knowing a child in their home who has faced bullying (31%), rape (14%) and child abuse (40%).

- 67 (15%) reported either themselves being a survivor of child abuse or

- closely knowing a child victim of abuse.

- 11% have ever heard someone at Gurdwara speak to issues of family violence.

- Only 3% reported being aware of any shelter being run for Sikh families.

|

Case Study 2

Approached by an elder man at the Sikh Family Center's monthly medical camp at Gurdwara wanting

some information and a clinic referral for their 3-year-old grandson. Grandson was undocumented, and

in need of a general checkup. Family did not speak English, had no means of transportation, and were

thus seeking a clinic in the area.

SFC volunteers looked up pediatric clinics for undocumented individuals based on the family's address.

We were able to find them one nearby and mapped out the clinic shuttle times from the local train

station along with bus route from their house to train station. |

Principle Three: Community-wide Services & Empowerment.

By providing services for all members of the community, SFC seeks to de-link any issue

from being particular to only one segment of the community. For example, while women

disproportionately constitute the population of domestic violence survivors, the issue of

domestic violence is far from “a women's issue" Often termed “family violence," its

reverberations are felt in the ecosystem of a domestic violence victim-survivor—e.g. her

parents, her children, etc.—and often transcend generations.

SFC's work does not focus on only the poor, or only immigrants, or only women. SFC thus, every day, challenges the notion of "the needy" as commonly understood in the

community. SFC is making a case that social sendees organizations and intra-community

work is sorely required for all of us to grow as a collective.

SFC works with the entire family, in turn hoping to involve the entire community. This

approach is also in keeping with the latest knowledge about effective interventions: for

example, the several benefits and necessities of involving men and boys in the movement to

end violence against girls and women.9

|

Case Study 3

A community member asked a young woman from the East Coast to call SFC. We will call this woman

Rani here, to protect her identity. Rani was trained as a physician before she got married. During the six

years of marriage, she had faced verbal and physical abuse by her in-laws, her husband, and now felt

alienated from her young daughter, who she was worried has trauma-related issues as well. Her husband,

also a physician, completely isolated her and any time she had a conversation with her family members,

he recorded these conversations and threatened to use these in court should she ever try to leave him.

The week she called us, her father was visiting. Her husband shoved her in front of her father. Her

father gave her the strength to call someone and find out options. She called 911 & then SFC.

SFC legal volunteers prepared Rani for the criminal hearing, informing her of her rights vis-a-vis

the District Attorney as well as Defense investigators. SFC then proceeded to contact organizations in

Rani's state that could help her get a restraining order: statistics show that danger for a domestic

violence victim-survivor is highest when she attempts to leave her abuser.

As Rani moved in with her young child to a new apartment, she had no money after rent. Her parents are in no position to support her financially. While linking her with local aid resources in her county, SFC in the meanwhile mailed her gift cards for groceries and childcare items.

For the next 3 months, as Rani became more acquainted with local resources in her county, SFC spoke with her on the phone to help alleviate fears and address concerns. At the same time SFC found male volunteers to speak with Rani's father, share his concerns and reassure him. Rani wanted to finally break the isolation imposed on her and with her permission, SFC got in touch with Sikh community

members in her area, to arrange for a few families to meet with her, drive her and her daughter to gurudwara, and check in on her as she went through this life change.

8 months after our initial call with Rani, she attempted reconciliation with her husband. SFC provided Rani non-judgmental information about the various dangers and legal disadvantages of this, while also supporting her in making decisions for herself.

2 months later. Rani's husband again turned her out of the house for "ill behavior." Rani is leaving the state to find safety, and SFC is again seeking an attorney to assist her in the next steps. |

Striking a Delicate Balance

SFC's work, the change it is attempting, comes with several challenges:

Capacity: Being entirely volunteer-run poses immediate issues of capacity.

Speed: The nature of the work as well as the commitment to empowerment mean

the work on each case SFC undertakes is slow and involved.

Follow-Up: SFC finds that the individuals served do not always follow through with our recommendations. While respecting the individual's agency/decision, we continue to provide them non-judgmental support toward better health & safety. When there isn't follow-up (often due to factors like transportation; family dynamics; cultural approach to timeliness and appointments), this too can give the perception of non-compliance.

Assumptions: SFC's work continuously requires explaining the need of such work—including the choice to work across segments of the community—while dispelling several myths about the prevalence of various issues. We also often encounter preconceived notions about health & resources, common to various linguistic & cultural minority groups.

Working with the above 3 guiding principles SFC is attempting to strike a delicate balance in its culture-change work: showing the community the mirror on shameful trends without shaming or alienating the very community it seeks to strengthen.

Footnote:

1 A version of this paper was first written for a poster presentation at Our Journeys 2014 Conference by the Sikh Feminist Research Institute (SAFAR), at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor on November 8, 2014. Paper Authors: Mallika Kaur, Gurpreet K. Padam & Bitika K. Kohii.

2 Our analysis draws from a mixed methodology: the quantitative data collected in SFC’s needs assessment surveys (we draw from 443 surveys entered in our database as of December 2014) as well as from qualitative interviews with SFC volunteers.

3 Angela P. Harris, Race and Essentialism in Feminist Legal Theory, 42 STAN. L. Rev. 581,585 (1990).

4See, e.g., "Battered women are found in all age groups, races, ethnic and religious groups, educational levels, and socioeconomic groups. Who are the battered women? If you are a woman, there is a 50 percent chance it could be you!" LENORE E. WALKER, THE BATTERED WOMAN 19 (1979).

5See, e.g., Margaret abraham, speaking the unspeakable: marital Violence among south Asian immigrants in the united States (2000); Mallika Kaur Sarkaria, Comment Lessons From Punjab's "Missing Girls": Toward a Global Feminist Perspective on "Choice" in Abortion, 97 CAL. L. REV. 905 (2009); Puri, et al„ "There is such a thing as too many daughters, but not too many sons": A qualitative study of son preference and fetal sex selection among Indian immigrants in the United States, 72 Soc. SCIENCE & MED. 1169 (2011).

6 Experts note that the value of even attentive and trauma-informed listening. "Often it is clear that telling the story with

my attention is transformative for the speaker." Nancy K.D. Lemon, A Transformative Process: Working as a Domestic Violence Expert Witness, 24 BERKELEY J. GENDER L.& JUST. 208 (2009).

7See, e.g., Quick Health Data Online, Office of Women’s Health, available at http:// www.healthstatus2 020.com/owh/ (last visited June 15, 2015).

8 Defined in the SFC Survey as: "a pattern of repeated violent behavior, whether physical, economic, sexual, and/or emotional— hitting, punching, choking, burning, hair pulling, and/or threats to harm or humiliate, in order to control or punish."

9 See, e.g., Department of Justice, "Justice Department Announces $6.9 Million in Grants to Engage Men in Preventing Crimes Against Women," available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-69-million-grants-engage-men-preventing-crimes-against-women (last visited June 15,2015).

© Sikh Family Center, a 501(c)3. |

Position Paper

Position Paper