Children of Khalistan have learnt to not look back in anger

Werewolves and blood-thirsty vampires set his nerves tingling and 2008's Twilight is his all-time favourite movie. He loves the bhangra-like vigour of hip-hop and finds calm in trance music. His eyes light up when he sits with his PC feverishly conjuring creatures that he says will one, not-too-distant, day catch Hollywood's fancy. He's the star of his batch at Frameboxx, a Chandigarh-based animation studio. Almost nothing in 20-year-old Kavardeep Singh's sunny countenance would tell you that he is the son of Dharam Singh Kastiwal, a Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) militant. "It's a great time to be alive," says the young man, born a few months after his father swallowed cyanide to escape capture by the Punjab Police in 1992.

Werewolves and blood-thirsty vampires set his nerves tingling and 2008's Twilight is his all-time favourite movie. He loves the bhangra-like vigour of hip-hop and finds calm in trance music. His eyes light up when he sits with his PC feverishly conjuring creatures that he says will one, not-too-distant, day catch Hollywood's fancy. He's the star of his batch at Frameboxx, a Chandigarh-based animation studio. Almost nothing in 20-year-old Kavardeep Singh's sunny countenance would tell you that he is the son of Dharam Singh Kastiwal, a Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) militant. "It's a great time to be alive," says the young man, born a few months after his father swallowed cyanide to escape capture by the Punjab Police in 1992.

Kavardeep is among some 300 young men and women looking at a future that promises to be distinctly different from the tragic path their fathers chose. Raised in private orphanages set up in the mid-1990s to nurture slain Sikh militants' children, the 'Children of Khalistan' are now ready to step into the real world.

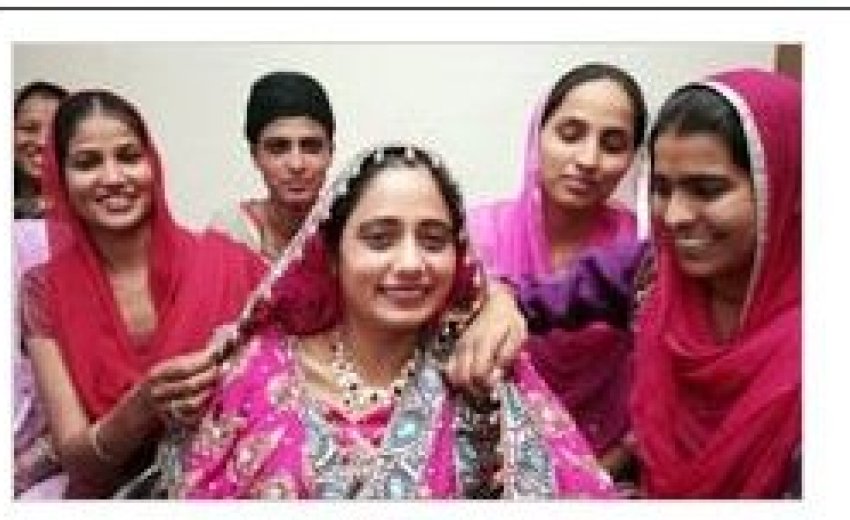

Not far from Chandigarh in Patiala's Kallar Bhaini village, Raj Kaur, 25, the older daughter of another BKI militant, Milkha Singh, killed in a 1992 encounter in Tarn Taran, is doing just that. It's her wedding day and her friends have just brought news of the groom's arrival. "They have come in an imported white car that's like three cars back-to-back (a stretch limousine)," gushes Harmanpreet, 21. The happy groom, 32-year-old British-Indian Roshan Singh, got engaged to Raj the first time he visited the Mata Gujri Sahara Trust (Kallar Bhaini) orphanage with a friend in 2010. "We kept in touch via email and phone. It's amazing to be finally together," he said. Raj, a trained medical laboratory technician, looks forward to life in the UK.

Not far from Chandigarh in Patiala's Kallar Bhaini village, Raj Kaur, 25, the older daughter of another BKI militant, Milkha Singh, killed in a 1992 encounter in Tarn Taran, is doing just that. It's her wedding day and her friends have just brought news of the groom's arrival. "They have come in an imported white car that's like three cars back-to-back (a stretch limousine)," gushes Harmanpreet, 21. The happy groom, 32-year-old British-Indian Roshan Singh, got engaged to Raj the first time he visited the Mata Gujri Sahara Trust (Kallar Bhaini) orphanage with a friend in 2010. "We kept in touch via email and phone. It's amazing to be finally together," he said. Raj, a trained medical laboratory technician, looks forward to life in the UK.

Fringing Amritsar, the historic, 800-year-old Sultanwind village's best-known address is the Shaheed Dharam Singh Khalsa Trust-an all-girl orphanage that supports 70 militants' daughters besides offering financial assistance to 48 boys studying in hostels across Punjab. Sukhjinder Kaur, 21, and her brother Satinderpal arrived in the orphanage as toddlers in 1996. Their father Sukhdev Singh Balaggan, a Khalistan Liberation Force (KLF) militant, was shot dead in an encounter outside Amritsar's Durgiana Temple in 1992. "I want to enjoy the very best life offers," says the computer science student. Not keen to dwell on bygones, she is happier talking about her passion for Bollywood heartthrobs: "Salman is the greatest!" but "3 Idiots is the best film ever." But John Abraham's "the man" for 20-year-old Sharanjit Kaur. The second-year fashion design student dreams of making "flowing Indian-style dresses for the catwalks". Sharanjit's father Jaimal Singh, from Asalpure village, was picked up by police in the winter of 1992 for harbouring militants. "He was never seen again," she says.

"I want to enjoy the very best life offers," says the computer science student. Not keen to dwell on bygones, she is happier talking about her passion for Bollywood heartthrobs: "Salman is the greatest!" but "3 Idiots is the best film ever." But John Abraham's "the man" for 20-year-old Sharanjit Kaur. The second-year fashion design student dreams of making "flowing Indian-style dresses for the catwalks". Sharanjit's father Jaimal Singh, from Asalpure village, was picked up by police in the winter of 1992 for harbouring militants. "He was never seen again," she says.

For most children of felled militants, the past is a fading recollection of fear and deprivation. mba student Simranjit Singh, 24, taken in by the Mata Gujri trust in 2007, recalls a panic-stricken childhood of recurrent midnight knocks and police raids at their Jammu home. A nephew of the Khalistan Zindabad Force chief Ranjeet Singh Neeta, who figures on India's list of most wanted terrorists in Pakistan, Simranjit's mother Maan Kaur was incarcerated in Delhi's Tihar Jail for months in 2000. Shortly after, the Jammu & Kashmir Police picked up his father Jagdish Singh, a truck driver, and tortured him in custody. "I must do well so that we are never poor again or in a place where the police can walk in and out at will," says the MBA student who is also preparing to take the Civil Services Examination.

Hardip Singh, 20, too has memories of khaki-clad policemen in his parents' home in Tarn Taran's Makhi Kalan village. This was after his uncle, Gurbachan Singh Manochal, the most feared terrorist of Punjab's border belt and chief of the Bhindranwale Tigers Force of Khalistan, was killed in an encounter outside Rataul village in March 1993. Two years later Hardip's father, Jagtar Jagga, who turned in his Kalashnikov rifle to work as a truck driver in Shamli, Uttar Pradesh, was killed in an accident. Today, Hardip studies electronics and communications at a Patiala polytechnic and wants to become a "successful engineer".

"We are the family many of these children would never have had," says Sandeep Kaur, 39, who set up the Shaheed Dharam Singh Khalsa Trust in memory of her husband Dharam Singh Kastiwal in 1996. Both here and at the Mata Gujri trust headed by another slain militant Kharak Singh Killi's widow Sohanjit Kaur, 45, the children look after each other. It's a rigorous routine: Everyone is up before dawn for nitt nem, the morning prayer, before setting off for school or college. Girls take turns in batches to cook the day's meals and the boys handles anything that requires fixing on the premises. "I'm forever in a rush," says Jaswinder, 18. A Class XII student at Sant Kirpal Academy on the outskirts of Kallar Bhaini, she wants to become a teacher. "I will help bring up an orphan girl like myself," she says. Sohanjit's daughter Harmanpreet Kaur, 21, a first-year MBA student at the College of Management & Technology in Patiala, dreams of starting a business of her own, but the militant's daughter will be a police officer if her mother has her way.

"We are the family many of these children would never have had," says Sandeep Kaur, 39, who set up the Shaheed Dharam Singh Khalsa Trust in memory of her husband Dharam Singh Kastiwal in 1996. Both here and at the Mata Gujri trust headed by another slain militant Kharak Singh Killi's widow Sohanjit Kaur, 45, the children look after each other. It's a rigorous routine: Everyone is up before dawn for nitt nem, the morning prayer, before setting off for school or college. Girls take turns in batches to cook the day's meals and the boys handles anything that requires fixing on the premises. "I'm forever in a rush," says Jaswinder, 18. A Class XII student at Sant Kirpal Academy on the outskirts of Kallar Bhaini, she wants to become a teacher. "I will help bring up an orphan girl like myself," she says. Sohanjit's daughter Harmanpreet Kaur, 21, a first-year MBA student at the College of Management & Technology in Patiala, dreams of starting a business of her own, but the militant's daughter will be a police officer if her mother has her way.

Contrary to Punjab's intensely patriarchal society, in the orphanages daughters are special. Between them, the two institutions have found good homes and spent generously on the marriage of nearly 100 girls. Like Raj Kaur, many militants' daughters have found grooms in the UK, New Zealand, Australia and Canada.

For the Children of Khalistan, violence is simply not an option. Hardip feels young people still willing to follow the dream of a Khalistan "are not thinking clearly". "Ensuring justice is important but you don't need guns for that," says Kavardeep. Twenty-two-year-old Rajbir Kaur's father, Baldev Singh Shakira (BKI), shot himself after being surrounded by security forces in Tarn Taran in 1992. "I shall be a judge one day so that people don't have to die like my father did," she says.

"Children in orphanages form their own families through intra-bonding and have somehow moved on, brushing aside anything that could be distressing in the past," says Kishwar A. Shirali, 74, a psychologist working with children who are victims of violence in Kashmir. "It comes from their common will to survive," she says

"Children in orphanages form their own families through intra-bonding and have somehow moved on, brushing aside anything that could be distressing in the past," says Kishwar A. Shirali, 74, a psychologist working with children who are victims of violence in Kashmir. "It comes from their common will to survive," she says

Police and intelligence officials have long suspected that the orphanages, particularly the Dharam Singh Khalsa Trust, serve as ultranationalist seminaries that methodically indoctrinate militants' children. But un Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights representative Jyoti Sanghera says the security establishment may be habitually overreacting and that the order of dress codes and prayer routines seen in religion-based orphanages "are more a means of instilling discipline among the children".

It seems to work. Through the decade and a half since the Sikh orphanages opened in Patiala and Amritsar, there isn't a single instance of a youngster becoming an addict or indulging in crime. In a state where more than two-thirds of all rural youth are given to some form of substance abuse, Sohanjit and Sandeep say their children are nothing short of "God's own miracle".