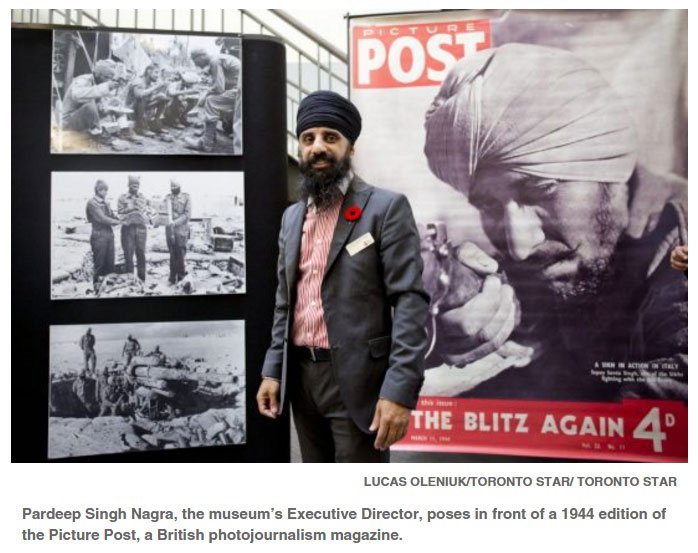

When Pardeep Singh Nagra was a kid in Mississauga, he didn’t see Sikh soldiers in his history textbooks.

Now, the 45-year-old is standing in a room where you can read about the first Sikh soldier to win a Victoria Cross (Captain Ishar Singh, 1921), look at propaganda posters extolling the virtues of the mighty Sikh whiskers, and admire row upon row of toy soldiers in turbans.

Nagra is the director of the Sikh Heritage Museum of Canada, and he was still up at 4:30 a.m. Sunday morning, putting the finishing touches on the museum’s “Outwhiskered” exhibit for Remembrance Day. The exhibit covers the 1800s to present, with a major focus on the two world wars, highlighting a history that is often forgotten.

“Let me tell you, I’m going to be all over the place, so don’t mind me,” Nagra says before launching into a whirlwind tour of several centuries of history.

“There is an Indian man in Flanders, but we’ve never been raised or nurtured here, even in our education systems, with this type of stuff,” he says, pausing by a photo of an Indian soldier in Ypres.

In Canada, 10 Sikh soldiers enlisted for the First World War. None enlisted in the Second World War, fed up with a country that hadn’t given them the right to vote, he said. (That would come in 1947.)

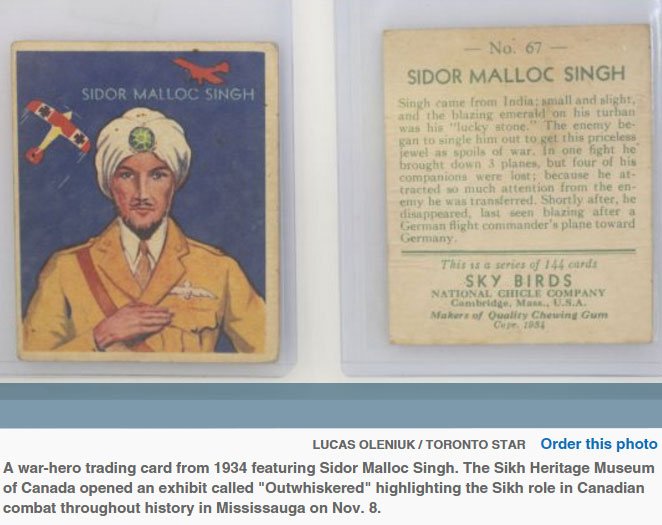

More than 65,000 Sikh soldiers fought in the First World War as part of the British Army and over 300,000 Sikhs fought with the Allies in the Second World War. Their reputation as fierce military men was a staple of Allied propaganda and even Kellogg’s cereal box inserts.

“They wear beards and a long moustache. And all of them wrap their heads in turbans. The Sikhs ride and shoot well. A great many are in the Imperial forces,” reads the back of one Sikh trading card, possibly from the 1940s or 1950s.

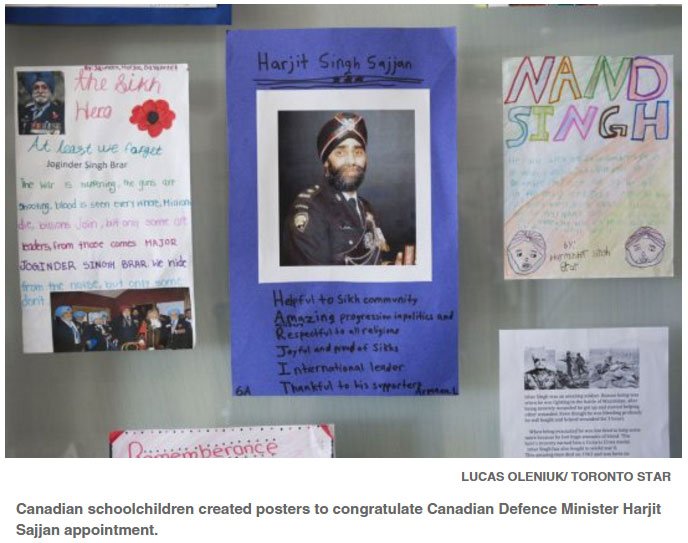

At the entrance to the museum, images of Canada’s newest Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan line the walls, drawn recently by students at Khalsa Community School in Brampton. One student has given Sajjan the acrostic poem treatment — H for “Helpful to Sikh community,” A for “Amazing progression in politics and military,” and on from there.

“They’re loving him,” Nagra says. “These are hot off the press.”

Newly elected MP Raj Grewal (Brampton East) stopped by the museum to check out the exhibit.

“With the recent appointment of Harjit Sajjan as the Minister of Defence, it’s just a great time, we’re really excited,” he says.

Sajjan was once commander of the British Columbia regiment, notable because in 1914, that regiment helped turn away the Komagata Maru from Vancouver’s harbour. The ship had been sitting outside the city for a two-month stalemate, with more than 300 British-Indian subjects on board, mostly Sikhs, hoping to come to Canada, but denied entry because of exclusion laws.

The ship returned to India around the same time the first group of Sikh soldiers arrived in France for war. “So we say, ‘Not wanted but greatly needed’ at the exact same time in history,” Nagra says.

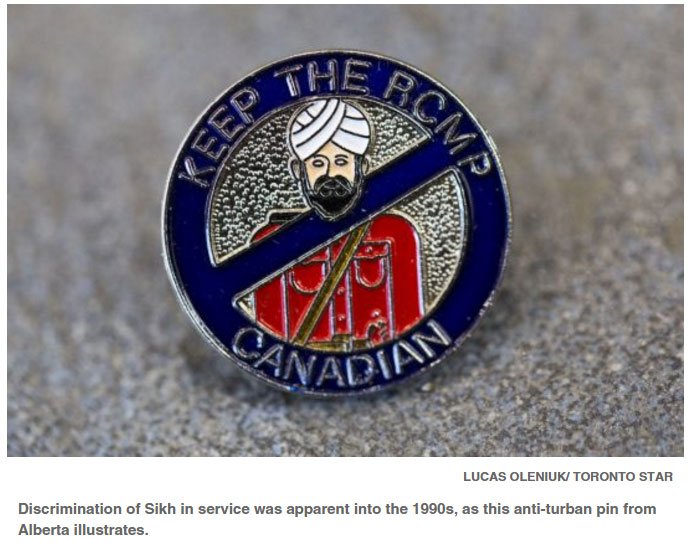

That kind of thinking is not just relegated to the days of black and white photos. Nagra flips through a binder and pull out pins from the 1990s: “Keep the RCMP Canadian,” one says, with a line through a turban.

Nagra walks over to a glass display honouring Hardit Singh Malik, the first Sikh to fly in combat with the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War; his flight commander was Canadian ace William Barker. Nagra begins to read aloud from a book:

“I consider it a privilege to write a foreword to an old and valued friend. My friendship with the author goes back long years, During World War One we were both officers in the Royal Flying Corps in which he served with distinction . . . years later we found ourselves as students together at Oxford.”

He flips the page to reveal the author.

“Lester B. Pearson,” he says, eyes wide. “Right?”

“This is the kind of legacy and history and partnership that we have.”

Angela Aujla, who came to the exhibit with two of her children, was captivated by the way the Sikh soldiers were turned into an object of fascination by the British.

“I have young children, and what I would like to see more of is when children learn about World War One and World War Two — who were the other individuals involved?” she says. “I think really it speaks to the larger issue about who is Canadian.”

Nagra hopes the exhibit will inspire Sikh children to “walk around with a little more sense of pride,” this Remembrance Day, with “the reflection that the red represents us as well and the sacrifices.”

At the exhibit, many people are already feeling that way.

“I’m very proud of the fact that the turban brought so much respect all over the world,” Amerjeet Saini, 35, says. “It shows there is only one religion in the world, and that is humanity.”