The Brutality of Mīr Mannū – Clay in the CREATOR's Hand

Even many years after the scourge of the Sikhs (Mīr Mannū, had died on November 4, 1753) one could see an old, stooping woman walk through the streets and alleys of Lāhaur. She had snow-white hair and a haggard face, and her gaze always seemed to be turned inward as if she was looking for something inside herself. She never spoke even a single word. Everyone that came across her timidly shunned her, for she radiated an immense sense of sorrow.

One day fortune smiled on her and decided to end her pain: As the woman crossed the market square of Lāhaur during an extraordinarily hot afternoon, she became dizzy and fainted. At once she was surrounded by sympathetic Sikhs, and one of them took heart, picked her up gently and carried her into his nearby house, where the whole Sikh family looked after her. It took some time for her to regain consciousness, and during this time she thought she heard someone call:

"Mātā, Mātā Jī".

"Mātā, Mātā Jī", had she really heard that? And there it was again:

"Mātā, Mātā Jī."

Something inside the old woman broke open. Her jaw began to move, and her teeth started grinding. A dry, throaty sob came out of her mouth that had been shut for so long, and then there was a cry that released all her pent-up pain into the world and made her sit up in fright. Then she was back in this world, looked at the many Sikhs that had gathered in the house and started speaking in a hurry:

"Mātā, Mātā Jī! Don't call me Mātā, Mātā Jī! I had a son who was my whole joy. He could be so cheerful and happy. And then...then came Mīr Mannū's torturers and snatched my darling child away from me. He cried 'Mātā, Mātā Jī' until his little mouth was silent forever. It was horrible. It is impossible to forget something like this. My child never stopped crying inside me. He cries, he cries day and night: Mātā, Mātā Jī."

The woman fell silent and cried quietly, and her tears had something liberating. She gratefully received a bowl of water from the lady of the house, drank the cool water in long sips and began her faltering narration:

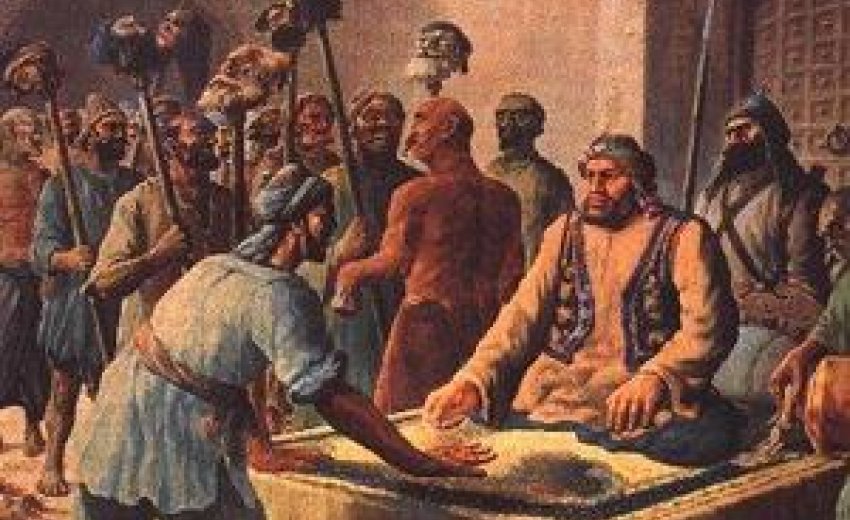

“I was a young girl when on April 9, 1748 Mīr Mannū, who was also called Mu´in -ul- Mulk, was appointed governor of Lāhaur and Multān after his victorious war against the Afgāns. He made the Hindū Kauṛā Mal his Divān. Mīr Mannū immediately called for the persecution of all of us, as if he had only waited for the day of his inauguration. About five hundred of us, including my family, had taken refuge in Ammritsar as we thought we were safe there. But many of our brothers and sisters in faith were hiding in the forests and mountains of the Pañjāb and Mīr Mannū had ordered the Rājās in these areas to catch all Sikhs. So they had our men hunted down, and when they had caught them, they cut off their hair and their beards. After that they were sent to Lāhaur in irons to be executed in the horse market, with the gaping crowd jeering as if was a merry feast. Our brothers' heads were piled up to form a pyramid, and they didn't shudder at their open mouths and their wide-open eyes that even in death told of the fear and the horror they had to suffer. VĀHIGURŪ. VĀHIGURŪ."

The old woman's voice broke. She remained silent for while, then took a sip of water and continued: “Can we call it luck that Divān Kauṛā Mal was well-disposed towards us Sikhs and the threat of a new Afgān invasion gave us a year of peace? I do not know, for afterwards the brutal murders continued. Four years had passed since Mīr Mannū had become governor. He left a bloody swath of destruction everywhere. I am slightly confused about at all, it was such a long time ago. But if I remember correctly, Ahimad Śāh Durānī attacked Lāhaur in 1752 and was defeated by Mīr Mannū, so that he became governor of the Afgāns as well and we lived in even greater horror. Mīr Mannū had not only raised new artillery units, but had also assigned 900 men especially to the task of hunting down infidels, and that meant above all us Sikhs. Sometimes his henchmen ran many miles, for a Sikh's head was worth ten rupees. Some who were not beheaded on the spot were even worse off, for they were beaten with wooden clubs until they were dead. VĀHIGURŪ. VĀHIGURŪ."

Again the old woman fell silent and struggled with her horrible memories. Small beads of sweat glistened on her forehead. Not one of the Sikhs in the room said anything, and some were crying softly.

"The terrible shadow of death continued to haunt us. Why? What had we done to them? Adīnā Beg Ḳhān sent Mīr Mannū about fifty Sikhs from the Doāb. He had them clubbed to death. What a clamour that was, what a wimpering and wailing, but also again and again calls of VĀHIGURŪ. VĀHIGURŪ. VĀHIGURŪ JĪ.

Mīr Mannū appealed to the Muslims and Hindūs to report all Sikhs that had gone into hiding, and promised them money for doing so. Many did as he wanted and got the bounty, but this must also be mentioned: There are no people that are only bad, and some Muslims and Hindūs did not agree with what Mīr Mannū and his henchmen did. But what could they do? They were afraid, remained silent and looked away. But there were also heroes and martyrs among them who hid their Sikh friends and paid for that with their own lives. May VĀHIGURŪ bless them.

When it was my turn, my husband had already been killed. They captured me and my son as well as all our neighbours and their children. We were dragged from our houses and thrown into prison, where we had to grind grain, 45 kilos a day. How were we to do that? Most of us couldn't, and they were punished by having a mill stone put on their chest whose weight slowly suffocated them. Only bread and water, day in, day out, there was nothing more for us and our children. They soon became so weak they fell asleep, and we mothers were grateful for that. We sang our holy songs to gain new strength. Then came the day that one of the henchmen tore my son from my arms. He cried and screamed:

'Mātā, Mātā Jī!'

He wriggled around in the man's arms, who simply held on to him and laughed.

'Mātā, Mātā Jī!'

And then..., and then..., he began hacking my son to pieces in front of my eyes.

'Mātā, Mātā Jī', help me!'

he cried until he finally was quiet and freed from his agony. VĀHIGURŪ. VĀHIGURŪ.

The man came to me with my son's bones and flesh and threw everything around my neck like a garland. His blood, which was still warm, seeped into me and burned my heart. And yet I never loved my son more then in these last moments. Other mothers and their children shared our fate. The butchers, who maybe had wives and children themselves, never stopped to ask: 'What if they were my wife and my child?'

But guilt catches up with us. It always catches up with us. I do not know how I survived the time after that. My memories are erased. On November 4, 1753 the prison doors were opened for the survivors. Mīr Mannū was dead. We were free, I was free. What did that freedom mean to me? My son was dead. My husband was dead. My whole family had been wiped out. I had nobody to go to. My captivity and the horrors I witnessed had turned me into an old woman with snow-white hair who never spoke a word again until today."

After she had finished her narration, all the Sikhs present remained silent. Nobody said anything. There is not always something one can say. The old woman rose slowly and went to the door. She stopped midway and turned around:

"Why does all this happen? I mean the good and even more the evil? Be that as it may, we are all clay in the CREATOR's hand."

When she reached the threshold she saw that night had folded up day into its dark cloth a long time ago. There was a silvery twinkling, as if of stars. A long way behind Lāhaur the pale moon smiled down on the old woman from the sky. She returned its smile and walked toward it.