|

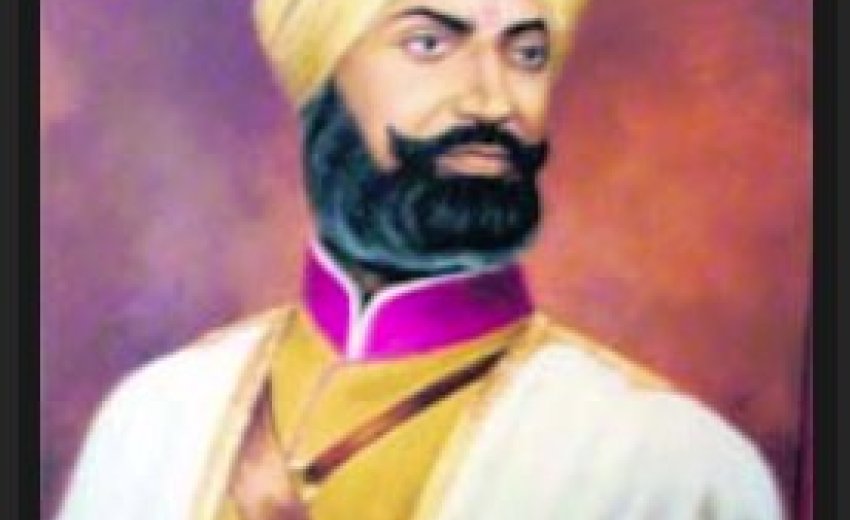

February 1, 2014: ZORAWAR SINGH (1786-1841), military general who conquered Ladakh and Baltistan in the Sikh times and carried the Khalsa flag as far as the interior of Tibet. About Zorawar Singh’s place of birth authorities differ. Major G. Carmichael Smyth, A Reigning Family of Lahore, says that he was a native of Kussal, near Riasi, now in Jammu and Kashmir state. Hutchison and Vogel have recorded that he was a native of Kahlur (Bilaspur) state, now in Himachal Pradesh. February 1, 2014: ZORAWAR SINGH (1786-1841), military general who conquered Ladakh and Baltistan in the Sikh times and carried the Khalsa flag as far as the interior of Tibet. About Zorawar Singh’s place of birth authorities differ. Major G. Carmichael Smyth, A Reigning Family of Lahore, says that he was a native of Kussal, near Riasi, now in Jammu and Kashmir state. Hutchison and Vogel have recorded that he was a native of Kahlur (Bilaspur) state, now in Himachal Pradesh.

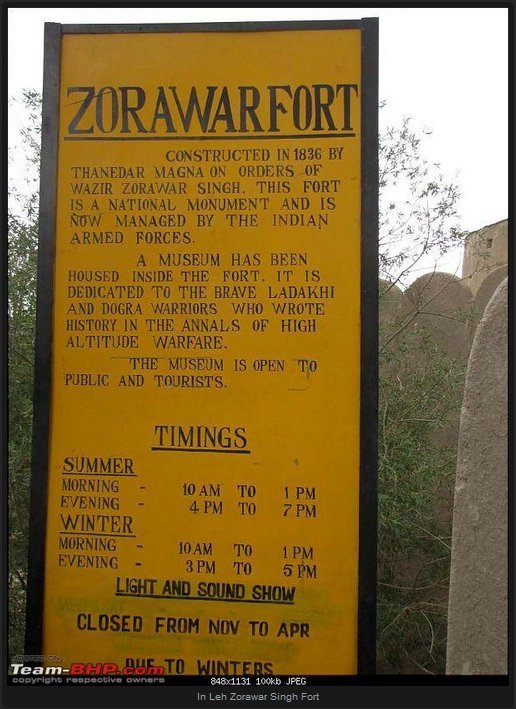

It is stated that when 16, Zorawar Singh killed his cousin in a dispute over property and escaped to Haridvar, where he met Rana Jasvant Singh, who took him to Galihan, now known as Doda, near Jammu, and trained him as a soldier. He joined service under Gulab Singh Dogra,Gulab Singh employed Zorawar Singh mostly for defending the forts to the north of Jammu. For some time he also worked as an inspector in commissariat of supplies where he did a commendable job by effecting a saving in the much needed provisions about 1823.When Raja Gulab Singh, the feudatory chief of Jammu under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, was appointed governor of Kishtvar, he appointed Zorawar Singh to administer the new district with the title of wazir.

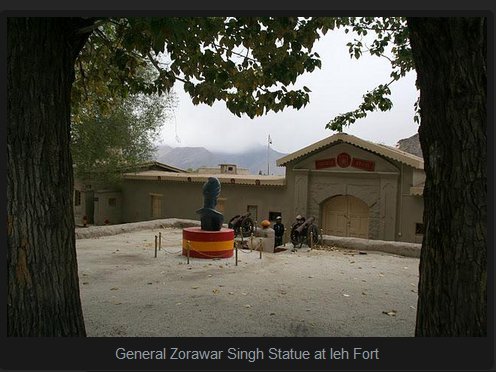

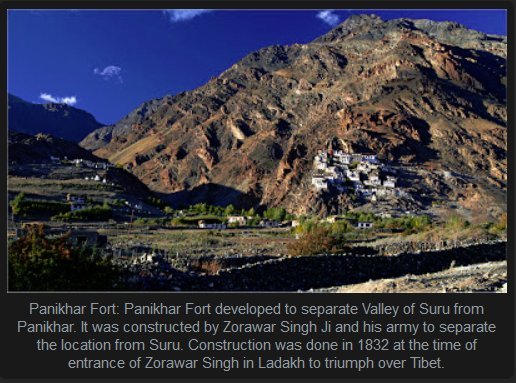

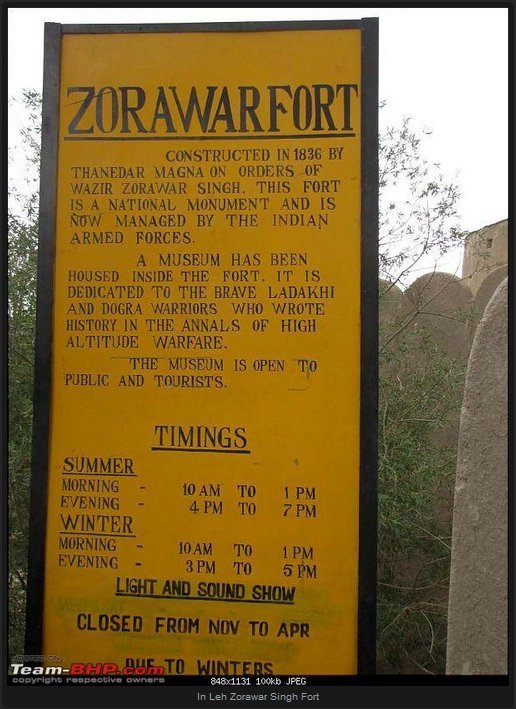

In Kishtvar, Zorawar Singh introduced fiscal and judicial reforms and had the old fort of Kishtvari rulers renovated. From here he led several expeditions into Ladakh, the first one in the series in July 1834. From Kishtvar, the Dogras entered the Sum valley. After fighting pitched battles at places such as Sanku, Langkartse, Kantse, Sot and Pashkam, the invaders pushed on to Leh, the capital of Ladakh. The Ladakhi king, Tsepal Namgyal, was made to pay war indemnity. He also undertook to pay an annual tribute of Rs 20,000 and acknowledged the suzerainty of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The Ladakhis, however, soon rose in revolt against their new masters and Zorawar Singh launched a second attack. This time he followed the short but difficult Kishtvar-Zanskar route. He quelled the rebellion, deposed the old king and appointed his prime minister and brother-in-law, Nagorub Stanzin, as the new ruler of Ladakh. But Zorawar Singh had to make two more incursions before Ladakh was annexed to the Sikh kingdom in 1840. The same year, Zorawar Singh attacked Baltistan, a Muhammadan principality in the Indus valley, to the northwest of Kargil. He defeated the Baltis and deposed Ahmad Shah, whose eldest son, Muhammad Shah, was installed as the new king of Baltistan. The Ladakhis, however, soon rose in revolt against their new masters and Zorawar Singh launched a second attack. This time he followed the short but difficult Kishtvar-Zanskar route. He quelled the rebellion, deposed the old king and appointed his prime minister and brother-in-law, Nagorub Stanzin, as the new ruler of Ladakh. But Zorawar Singh had to make two more incursions before Ladakh was annexed to the Sikh kingdom in 1840. The same year, Zorawar Singh attacked Baltistan, a Muhammadan principality in the Indus valley, to the northwest of Kargil. He defeated the Baltis and deposed Ahmad Shah, whose eldest son, Muhammad Shah, was installed as the new king of Baltistan.

Zorawar Singh next turned his attention towards western Tibet. The conquest of Tibet was an ambition he had harboured in his heart for some time and, as Sohan Lal Sun, the court chronicler of the Sikh times, records, this was the suggestion he proffered to Maharaja Ranjit Singh when he in March 1836 waited on him at the village of Jandiala Sher Khan to pay nazarana. He told the Maharaja that he was ready to “kindle the fires of fighting” and “by the grace of ever triumphant glory of the Maharaja, he would take possession of it.” The Maharaja, however, was not willing to allow him to undertake the adventure.

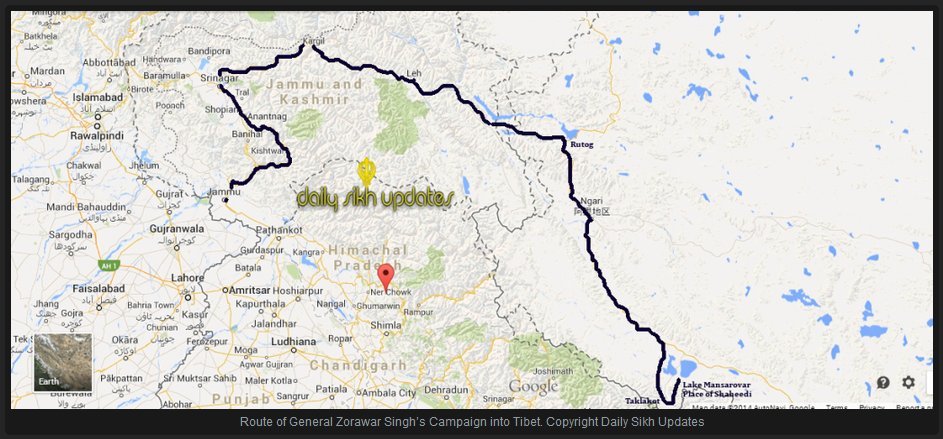

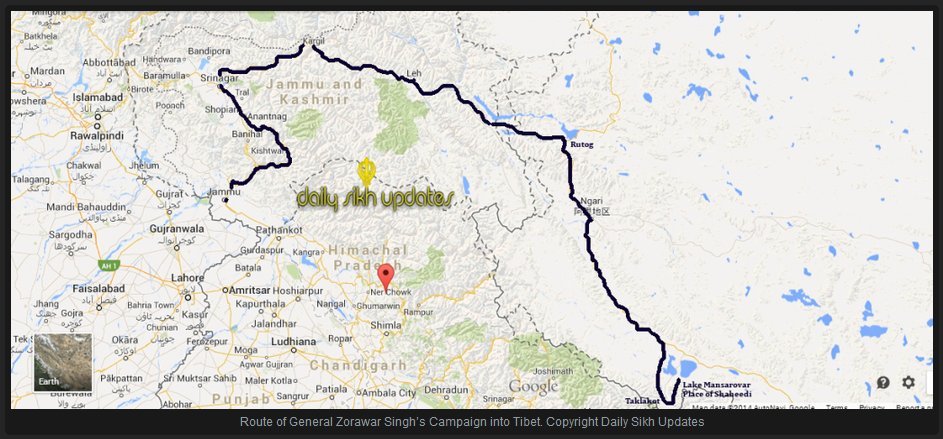

Zorawar Singh had his chance in the time of Ranjit Singh’s successor, Maharaja Sher Singh. In April 1841, by which time the conquest of Ladakh had been completed, he marched into Tibet at the head of a large army and within six months had conquered territory to the north west of the Mayyum Pass. But then a strong Tibetan army descended down from Lhasa and confronted the invaders at Tirthapuri, near Lake Manasarovar. Zorawar Singh could get no reinforcements from Leh or from any other place as heavy snows had blocked all the passes. He fought many a pitched action in the vicinity of Lake Manasarovar and was killed in the last one of these on 12 December 1841.

Although this great conqueror perished midcampaign, his initiative did not go unrewarded. In September 1842 a treaty was signed by representatives of Chinese and Lhasa governments on the one hand and of Khalsa Darbar and Gulab Singh on the other which extended the Sikh, and hence Indian, frontiers to their present international boundary. The whole of Ladakh thus became a part of the Indian territory.

An English version of the treaty is as follows : As on this auspicious day, the 2nd of Assuj, samvat 1899 (16th/17th September 1842) we, the officers of the Lhasa (Government), Kalon of Sokan and Bakshi Shajpuh, commander of the forces, and two officers on behalf of the most resplendent Sri Khalsa ji Sahib, the asylum of the world, King Sher Singh ji, and Sri Maharaja Sahib RajaiRajagan Raja Sahib Bahadur Raja Gulab Singh, i.e.. the Muktar-ud-Daula Diwan Hari Chand and the asylum of vizirs, Vizir Ratnun, in a meeting called together for the promotion of peace and unity, and by professions and vows of friendship, unity and sincerity of heart and by taking oaths like those of Kunjak Sahib, have arranged and agreed that relations of peace, friendship and unity between Sri Khalsa ji and Sri Maharaja Sahib Bahadur Raja Gulab Singh ji, and the Emperor of China and the Lama Guru of Lhasa will hence forward remain firmly established forever ; and we declare in the presence of the Kunjak Sahib that on no account whatsoever will there be any deviation, difference of departure (from this agreement).

We shall neither at present nor in future have anything to do or interfere at all with the boundaries of Ladakh and its surroundings as fixed from ancient times and will allow the annual export of wool, shawls and tea by way of Ladakh according to the old established custom. Should any of the opponents of Sri Sarkar Khalsa ji and Sri Raja Sahib Bahadur at any time enter our territories, we shall not pay any heed to his words or allow him to remain in our country. We shall offer no hindrance to traders of Ladakh who visit our territories. We shall not even to the extent of a hair’s breadth act in contravention of the terms that we have agreed to above regarding firm friendship, unity, the fixed boundaries of Ladakh and the keeping open of the route for wool, shawls and tea. We call Kunjak Sahib, Kairi, Lassi, Zhon Mahan, and Khushal Chon as witnesses to this treaty.

References :

- Suri, Sohan Lal, ` Umdat-ut-Twankh. Lahore, 1885-89

- Hutchison, J., andJ.Ph. Vogel, History of the Punjab Hill States. Lahore, 1933

- Charak, Sukhdev Singh, Indian Conquest of the Himalayan Territories. Pathankot, 1978

- Smyth, G. Carmichael, A History of the Reigning Family of Lahore. Calcutta, 1847

- Hasrat, BiramaJit, Anglo-Sikh Relations, 1799-1849. Hoshiarpur, 1968

|

General Zorawar Singh | |

Saudagar Mal Sharma

During the month of August-September 2012, I undertook pilgrimage of Kailash Mansarovar. Since the mount Kailash and lake Mansarovar are situated in Tibet, one has to travel through the length and breadth of great Himalayas confronting the cruelties of bad weather and heights 19000 feet above sea level. Besides being a pilgrim, I was extra ordinary enthusiastic to visit the Samadhi of great General Zorawar Singh, who embraced martyrdom for the expansion of territorial limits of Jammu and Kashmir/India. It had been my constant solicitation to the Tibetian Guides to let me not miss the glimpse of the memorial of the warrior of Dogra army.

There are conflicting views about Zorawar Singh’s origin. It is said that he was a native of Kussal near Reasi, but on the basis of information from family sources ( a great grandson) of Zorawar Singh to a historian, it is said that Dogra General was born in 1786 AD at village Ansara in Hamirpur district of Himachal Pradesh. In the Gulab Nama, which is an authentic account, the word ‘Kahluria is written after the name of Zorawar Singh which lends support to the view that he was a Rajput and belonged to the Kahluria Mians, who are said to be the descendants from Rajas.

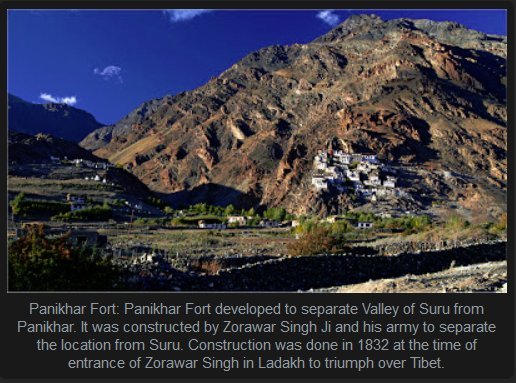

There is paucity of information about Zorawar Singh’s childhood and early career. However, it is said that when sixteen, he killed his cousin over property feud and left for Haridwar to atone his guilt. Here in about 1803, he met Rana Jaswant Singh, a Jagirdar of Gilihan near Jammu. Rana brought him to his place and took him in his service. After some years, Zorawar Singh left Rana’s service and joined that of Raja Gulab Singh. He impressed Gulab Singh with his innate ability and earned the title of ‘Wazir’ on bringing about fiscal and judicial reforms in his kingdom. The brave Governor of Kishtwar Zorawar Singh Kahluria, on sensing great internal unrest in Ladakh thought of carrying out invasion upon Ladakh in July 1834. He marched with 5000 soldiers crossing Maryum La Pass (14700 feet) covering a distance of 336 miles via Suru. During the invasion, Zorawar Singh and his army had to face stiff resistance from Ladakhis in the 1834-35, but the disciplined army under General Zorawar Singh conquerred and annexed the territory.

The General invaded Baltistan and Skardu in 1839-40, the region where there was no standing or regular army to confront the highly trained and tactically sound army. The invaders had to face high mountain, impassable frozen rivers, cold and starvation while fighting the Baltis. At last in 1840 Baltistan lost independence and came under the control of Raja Gulab Singh.

Wazir Zorawar Singh thought of establishing empire in Western Tibet after the conquests of Ladakh and Baltistan. His attack on Western Tibet was three pronged and well planned. A contingent of army was under the command of Ghulam Khan, Nono Sunnum and the third column was under the command of Zorawar Singh himself following the route south of Pangong Lake. In the month of August 1841, a fight broke out between the two and bother sides suffered human loss, but the Tibetan could not stand Dogra onslaught and fled towards. Taklakot. After some feeble resistance, in Sept 1841, the Dogras took possession of Taklakot. Zorawar Singh’s conquest of western Tibet was now complete.

In west Tibet are located the holy mount Kailash, Lake Mansarover and lake Raksh Tal. A high peak is considered by the Hindus as the site of Lord Shiva’s seat. It is said to be the most scared spot on earth.

The Dogras, under General Singh were not allowed to reap the fruits of their new conquests in Western Tibet. Lhasa provided reinforcement to General Pishi, about 10000 Tibetan army to fight back the invaders. Meanwhile, the winter had set in and the heavy snow fall had closed mountain passes. The Tibetan army invaded Taklakot in early November and also surrounded the other Dogra military posts. On Dec 12, Zorawar Singh was hit on the right shoulder and he fell down from his horse near the village Do-yo, but he did not give in putting to death many of his enemies with the sword in his left hand, although badly wounded. However, he was killed by a Tibetan warrior on December 12, 1841 in the vicinity of Taklakot.

In order to perpetuate the memory of a great General’s association with Tibet, the Tibetans constructed a memorial in the shape of a chorten or Samadhi wherein the remains of the dead General have been kept. The Samadhi is a mere heap of stones erected at a distance of a few kilometers from Taklakot in a secluded place. No concrete foundation and brick walling has been done. The tragic end remained unceremonious. The Government should have taken steps for construction of a suitable memorial in the ever lasting memory of the great General, who created history. He will remain shinning till the world exists. This however, is a unique case in the history of world where a memorial stands erected by the conqueror in favour of gallant enemy.

The Sikh Conquest of Ladakh and Tibet: 1834-40 A.D.

SHER SINGH, I.A.S. (RETD)*

* Bains-Kutiya, H. No. 1897, Urban Estate, Phase II, Patiala. 147002.

IN A PRAGMATIC FOREIGN POLICY, no country is a permanent friend or foe; only self-interest is the key. That Maharaja Ranjit Singh was a past-master in diplomacy is amply proved by his policy towards Nepal after defeating them in the Sikh-Gorkha battle at Kangra in 1809, after they approached him to have a common alliance against the British after the outbreak of Anglo-Nepalese war of 1814-16.

Ranjit Singh is reported to have told Bhai Gurbaksh Singh, Dhanna Singh and others, in a private conversation in 1814: “though apparently sincere friendship is supposed to exist between myself and the English people, yet in reality, our relations are merely formal and conventional. Therefore, I had thought out to myself that in case the English should act differently in their dealings with me, I would call upon the Gurkhas and make friends with them and, in case they showed any hesitation, I intended to make over the fort of Kangra to them to win their comradeship. Now they have been expelled from the mountains and it cannot be said when they would cherish a desire for the above-mentioned region. I never expected such a thing to happen that the mountainous region would be evacuated by them so suddenly.”

It appears that, on hindsight, the Maharaja felt repentant for defeating his true ally – Nepal, and never wanted them to evacuate the mountainous region, because he realised the strategic importance of such a region. He knew that the Sikh nation would be invincible only if it had inaccessible and unsurpassable Himalayan ranges under its control. So, having lost territorial contact with Nepal (due to British victory over Nepal in Anglo-Nepalese War 1814-16), the Maharaja was looking forward to winning Ladakh and Tibet, to restore the territorial contact with Nepal. In this connection, we should note Wade?s despatch to the British secretary, which reads: “The information gained by me in my late visit to Lahore was that, among other objects of ambition, Raja Gulab Singh had in taking Ladakh, one was to extend the conquest down the course of the Spitis until they approached the north-eastern confines of the Nepalese possessions in order that he might connect himself with that Government ostensibly with the view to promote the trade between Lhasa and Ladakh, which the late commotions in Tibet have tended to interrupt, but in reality to establish a direct intercourse with a power which he thinks will not only tend greatly to augment his present influence but lead to an alliance which may at some future period be of reciprocal importance.”

So, far a long time Ranjit Singh's intention of invading Ladakh was an open secret. We learn from Cunningham “The History of Sikhs” when Mr. Moorcraft was in Ladakh (in 1821) the fear of Ranjit Singh was general in that country and the Sikh Governor of Kashmir had already demanded the payment of tribute.” But the opportunity came in 1834, when Britishers were trying to chek his advance towards East beyond Sutlej and towards West, Ranjit Singh burst forth towards North beyond Himalayas. So, far a long time Ranjit Singh's intention of invading Ladakh was an open secret. We learn from Cunningham “The History of Sikhs” when Mr. Moorcraft was in Ladakh (in 1821) the fear of Ranjit Singh was general in that country and the Sikh Governor of Kashmir had already demanded the payment of tribute.” But the opportunity came in 1834, when Britishers were trying to chek his advance towards East beyond Sutlej and towards West, Ranjit Singh burst forth towards North beyond Himalayas.

The plateau of Ladakh is in the upper Indus valley, and two-thirds of the people were Bhutias, and the Rajas?s title was known as Geeape. Rajas were frequently changed who used to turn Lamas (priests) afterwards. The troops of the Raja used Match-locks, bows, arrows and swords. They were mostly horsemen and numbered about 8000. The infantry was around 1200 in number and used the same arms. Revenue of Ladakh Raja was approximately Rs. 5 lakhs p.a. which used to be paid in kind. The only stook-in-trade was shawl-wool but the trade was not inconsiderable. Ladakh has no relation with China, of a political nature, had no connection with Lhasa save that which arose from community of religion, manners, and close proximity.

In 1820 and 1821, when Moorcraft came to Ladakh with a view to opening up British trade relation, and buying horses and wool, the Ladakh Government tendered its allegiance to the British rulers through him, but as the British authorities had not yet become apprehensive of accumulation of wealth and power in the hands of Ranjit Singh, Moorcraft was disowned by them and they tried their best to quiet the alarms of Ranjit Singh.

Taking advantage of the rift in the ruling family of Ladakh Maharaja Ranjit Singh despatched his General Zorawar Singh who was posted at Kishtwar, at the head of a 8000 strong force of cavalry and infantry towards Ladakh in July 1834 (may be May 1834) and declared that an estate, anciently held by the Kishtwar Chief must be restored. At that time, Dr. Henderson happened to be present there. The Raja of Ladakh gave out that he was a British ambassador and had been sent to ratify the treaty that Moorcraft had entered into with him. But he knew that Dr. Henderson was only an explorer. For three months the operation of Zorawar Singh was suspended. The matter was referred through Raja Golab Singh to Maharaja, who in turn referred it to British Resident at Ludhiana. The Resident assured the Maharaja that Dr. Henderson was not their representative.

On 16 Aug. 1834 General Zorawar Singh defeated a 5000-strong Ladakhi forces and advanced towards its cpaital, Leh leaving small detachments at the imperial places en route to secure his rear. At Leh he deposed the reigning king and set up the latter's rebellious minister in stead. He placed a garrison at Leh and fixed a yearly tribute of Rs. 30,000 as levy. He retained some districts along the northern slopes of the Himalayas. According to Cunningham, he did not reach the capital until early 1835. As the winter approached, the General left for Jammu, and thence for Lahore, with a clutch of presents for the Maharaja.

He presented Nazrana before Maharaj Ranjit in the winter of 1835 [1836, according to Khushwant Singh: The History of the Sikhs, Vol. I]. The General requested Maharaja to allow him to carry Maharaja?s arms to the borders of China. But the astute Maharaja, knowing fully well that „Padishah? of China had 1,20,000 soliders ready to fight, advised him not to venture into little Tibet.

According to Cunningham, “The dispossessed Raja complained to the Chinese authorities in Lhasa, but the tribute continued to be regularly paid by his successor, no notice was taken of the usurpation.” [The History of the Sikhs, p. 272.]

Taking advantage of General Zorawar Singh's absence and cold weather, the Ladakhis wiped out many of the small garrisons at Suru to sword. Zorawar Singh had to repeat his previous performance. Though death overtook Maharaja Ranjit Singh on 27 June 1839, Zorawar went ahead with his conquering spree during the Regency of Nau Nihal Singh.

First he turned his attention to Baltistan – Skardu, Gilgit and Humza, [from Leh this area is down the Indus]. As Balties were better fighters than Ladakhis, the General decided to take them one by one. He dealt with Skardu forces first and defeated them in July 1840. The rulers of Gilgit and Humza submitted without giving a fight. Gilgit and Humza fall on the National Highway built by Chinese across India and Nepal border, linking Rudok, Tashigong and Gartok – the places invaded later by General Zorawar Singh.

Zorawar Singh belonged to a Rajput family from Kahlur near Pathankot. He was first employed as a Sepoy in the forces of Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu – a tributary of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. His energy and miltary latent was recognised and he was promoted as a petty official to Gulab Singh. At this time Zorawar Singh was brought to the notice of Maharaja. From then on his rise was meteoric and he became a General.

Having subdued Baltistan, Zorawar Singh turned his attention towards Tibet. For this expedition he recruited Ladakhis and Balties with little bit of Dogras. This force had very little of Sikh soldiers and this factor ultimately led to his debacle. He collected a 5000 strong force at Leh from where he commenced his advance (May 1841) towards western Tibet and entered Tibet near Tashigong [From Leh up the Indus river] and captured Rudok towards middle of 1841 and then Gartok and Garo – 1841. Rudok is towards north of Tashigong and Gartok and Gar (Gare) are towards East. Gartok is situated at approximately the same longitude and latitude. May be these two places are very close or the same place having two names. Gartok and Gar are jut on the top of Khojarnath pass in the North – West corner of Nepal, from where people enter into Nepal from Tibet. So Maharaja Ranjit Singh?s dream of establishing land route with Nepal, by-passing occupied India, was realised.

But General Zorawar Singh did not stop here. Being over-ambitious he went on advancing into Tibet because Tibetans did not offer much resistance, and wanted Sikh General to first exhaust himself before they dealt with his force. The General was caught in their trap. His forces had been thinning as he had to guard his rear also and due to disturbed circumstances at home could not expect much reinforcements.

Ultimately, there was collision with the Chinese and the Tibetans gave him a battle in the first week of December, at an altitude of 13000 feet. The battle continued for 3 days during which Zorawar Singh himself was killed on 12 Dec. 1841. The Tibetans took a heavy toll of Sikh army, and the survivors returned to Ladakh.

The three main reasons for General Zorawar Singh?s deafeat were: Firstly, his recruiting Ladakhis, Balties and Dogras, with very little Sikh representation, for the Tibet expedition, [culturally, linguistically they felt one with Tibetans, and not with their General]. Secondly, no support came from Lahore as Maharaja Nau-Nihal Singh was a minor and all his Generals were busy in conspiracies in eliminating each other. Thirdly, ignoring the advice of the wise Maharaja Ranjit Singh, he provoked a mighty power of Asia, viz, China. The result was catastrophic.

Maybe the General was over-ambitious and wanted to set-up an independent Sikh state in Tibet and W. Nepal. Though the bold attempt failed, in the conquest of Tibet, it succeeded in winning “The Great Himalayas so far considered unsurpassable – A rare victory indeed.” |

|

February 1, 2014: ZORAWAR SINGH (1786-1841), military general who conquered Ladakh and Baltistan in the Sikh times and carried the Khalsa flag as far as the interior of Tibet. About Zorawar Singh’s place of birth authorities differ. Major G. Carmichael Smyth, A Reigning Family of Lahore, says that he was a native of Kussal, near Riasi, now in Jammu and Kashmir state. Hutchison and Vogel have recorded that he was a native of Kahlur (Bilaspur) state, now in Himachal Pradesh.

February 1, 2014: ZORAWAR SINGH (1786-1841), military general who conquered Ladakh and Baltistan in the Sikh times and carried the Khalsa flag as far as the interior of Tibet. About Zorawar Singh’s place of birth authorities differ. Major G. Carmichael Smyth, A Reigning Family of Lahore, says that he was a native of Kussal, near Riasi, now in Jammu and Kashmir state. Hutchison and Vogel have recorded that he was a native of Kahlur (Bilaspur) state, now in Himachal Pradesh.

The Ladakhis, however, soon rose in revolt against their new masters and Zorawar Singh launched a second attack. This time he followed the short but difficult Kishtvar-Zanskar route. He quelled the rebellion, deposed the old king and appointed his prime minister and brother-in-law, Nagorub Stanzin, as the new ruler of Ladakh. But Zorawar Singh had to make two more incursions before Ladakh was annexed to the Sikh kingdom in 1840. The same year, Zorawar Singh attacked Baltistan, a Muhammadan principality in the Indus valley, to the northwest of Kargil. He defeated the Baltis and deposed Ahmad Shah, whose eldest son, Muhammad Shah, was installed as the new king of Baltistan.

The Ladakhis, however, soon rose in revolt against their new masters and Zorawar Singh launched a second attack. This time he followed the short but difficult Kishtvar-Zanskar route. He quelled the rebellion, deposed the old king and appointed his prime minister and brother-in-law, Nagorub Stanzin, as the new ruler of Ladakh. But Zorawar Singh had to make two more incursions before Ladakh was annexed to the Sikh kingdom in 1840. The same year, Zorawar Singh attacked Baltistan, a Muhammadan principality in the Indus valley, to the northwest of Kargil. He defeated the Baltis and deposed Ahmad Shah, whose eldest son, Muhammad Shah, was installed as the new king of Baltistan.

So, far a long time Ranjit Singh's intention of invading Ladakh was an open secret. We learn from Cunningham “The History of Sikhs” when Mr. Moorcraft was in Ladakh (in 1821) the fear of Ranjit Singh was general in that country and the Sikh Governor of Kashmir had already demanded the payment of tribute.” But the opportunity came in 1834, when Britishers were trying to chek his advance towards East beyond Sutlej and towards West, Ranjit Singh burst forth towards North beyond Himalayas.

So, far a long time Ranjit Singh's intention of invading Ladakh was an open secret. We learn from Cunningham “The History of Sikhs” when Mr. Moorcraft was in Ladakh (in 1821) the fear of Ranjit Singh was general in that country and the Sikh Governor of Kashmir had already demanded the payment of tribute.” But the opportunity came in 1834, when Britishers were trying to chek his advance towards East beyond Sutlej and towards West, Ranjit Singh burst forth towards North beyond Himalayas.