Art and architecture express the aspirations of a people. About the glory and splendor of the Catholic faith there are many physical testaments and yet with each year that similar witness to the Sikh tradition diminishes. It is in this context that the work of Dr. Pannu is important; its value surely to be appreciated by future generations as they start to explore the bounties of their heritage.

It takes an organized mind to systematically parse literature for over a decade and help define the most important vestiges associated with the Sikh heritage in Pakistan. Dr. Pannu has done an admirable job in compiling that record.

His mission becomes an existential one for him and for Sikhi as he indicates in his preface quite eloquently:

“I get the feeling that I can now almost talk to these buildings, even listen to them. Each individual structure has a unique past and a story to tell, but to my mind there is one invisible disenchantment and complaint that they all seem to utter “we are waiting, we are waiting for the everlasting peace to prevail in the region so that the heritage connoisseur can visit us freely”.

For the initiate to the Sikh tradition this book will serve as an introduction to the evolution of the Sikh community. For those who are well versed in Sikh history, they will revel in snippets of analysis of the historical nuances that Dr. Pannu can offer by examining the original sources, be it by Sikhs or by Muslims. In any event, the book serves as a much-needed balm for the Gurdwaras and their plaintive calls for rejuvenation, restoration and preservation.

The task that Dr. Pannu undertook in his research to document the places of interest surrounding the Gurus was infused with a scientist’s desire to prune fact from fiction. In the process, he seeks to distill the essence of the message of the Gurus; explore the evolution of the Sikh community; dice up folklore and glean the important stories and milestones in Sikh history.

After the catastrophe that was the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 the Sikh Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (“SGPC”) took stock of the Gurdwaras that had to be preserved in Pakistan. However, some 178 were abandoned in western Punjab with other notable buildings also left orphaned. Sikhs suffered a loss of more than 75% of their historical religious shrines, notes the author. In recounting the Gurdwaras associated with the first Guru, Dr. Pannu shows dexterity in analyzing the hagiographical accounts as manifested in the Janamsakhis (birth stories of Guru Nanak) and texts written by local Muslim authors. The exploration of historical sites cannot be disassociated from culling Sikh literature and of course the Guru Granth Sahib -the Sikh scripture. In this vein in chapters 38 (Sharenke), 31 (Gurdwara Dukh Nivaran), and 73 (Gurdwara Shahid Ganj Bhai Mani Singh), the author tracks down and reveals the fascinating rare handwritten recensions of the Guru Granth Sahib.

It is Dr. Pannu’s ease with historiography that renders this book that much more an easy read – he does not get bogged down in the nuances of academia and yet does not accept at face value the faux tales surrounding the Gurus. In his recounting of the memorialization of the birthplace of Guru Nanak, Dr. Pannu acknowledges the prodigious contribution of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and also the understated role of the Udasi Mahants (administrators) rightfully discredited later for their corruption of the role as administrators of the Sikh institutions. In the initial phase however they did much to preserve Sikh Gurdwaras especially during the massacres of the 18th century. In hindsight it would have been helpful if Dr. Pannu had delved into the historical context and origins of groups such as the Namdharis and Nirmalas. The author does, however, traces the history of Udasi tradition and identifies the historically significant place in chapter 48 of Sri Chand’s meditation site (Gurdwara Tahli Sahib). The author learns about the illustrious past of Baba Jamait Singh, who he characterizes as a member of the Namdhari Kuka movement, in chapter 74 (Gurdwara Baba Jamait Singh Ji).

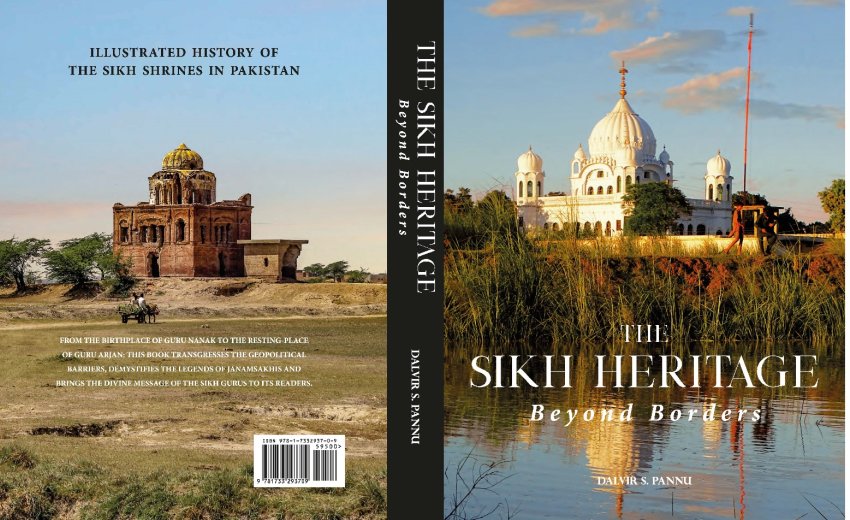

Dr. Pannu has systematically divided the areas of interest in Pakistan into six districts. He then proceeds to relay the import of each of the shrines both from a historical and faith perspective. Interlaced in his narrative are the stories surrounding the Sikh Gurus. Indeed, in recounting the early story of Guru Nanak and his precocious understanding of the religious precepts prevalent in Hinduism and Islam, Dr. Pannu remarks on the importance how knowledge is conveyed and preserved. In particular, he notes that the Patti (verses written as an acrostic) were first written by Guru Nanak (which then became the foundation of the Gurmukhi script) hence significantly undermining the importance of Brahmins and their hegemony of the dissemination of knowledge. Of course, the second Guru Angad developed the Gurmukhi script. Indeed, it is the interplay of these stories and the analysis of their accuracy and the splendid photographs that were commissioned by the author, that make his book that much more interesting and insightful.

In recounting the hagiographical stories or miracles surrounding Guru Nanak, Dr. Pannu does not challenge faith but as a man of science he offers perspective. He notes that the Sufi literature that was imbued by the learned and inhered by the general public was replete with miracles. Hence there was a natural affinity with the narrative of a holy man and his ability to perform miracles. This was widely accepted as part of folklore. There is a detailed discussion of why the Bala Janamsakhi is fictitious- an attempt to elevate the life of a Jatt has been shown to be largely a fabrication and an exercise in self-aggrandizement and propaganda. The author’s recounting of the history of various Gurdwaras such as Gurdwara Janam Asthan are also an interesting (albeit grisly) foray into the birth of the SGPC and the control of Gurdwaras by the Sikhs (the Gurdwara reform movement) as they threw off the hold of the corrupt Mahants. The legal complexities are ably dissected by Dr.Pannu, the trials between the Udasi Mahants and the SGPC are described in great detail in numerous chapters. For instance, chapter 75 (Shrine of Bhai Pirthi) offers insight into a 10-year legal dispute (1921-1931). No Guru had ever visited this shrine, hence the SGPC's counsel could not lay the legal foundations to conclude that it was a Sikh Gurdwara. To support his findings, the author has retrieved data from the official Indian Law Reports, Lahore Series, 1931, which are conveniently referenced in the bibliography and end notes. Gurdwara Babe di Ber Sialkot is generally thought to have been the first to be taken over under its control by SPGC. However, in chapter 56 (Gurdwara Chowmalla Sahib), the author cites a February 22, 1922, confidential report of V. M. Smith, chief of the Secret Service Department, which notes that “Gurdwara Chowmalla Sahib was the first Gurdwara to be captured by the Sikhs”.

Also, other important historical episodes in Sikh history are given reference. For example, in the examination of Gurdwaras in Sheikhupura the author recounts the story of Nawab Kapur Singh Virk and how he was given the title of Nawab by the governor of Lahore Zakariya Khan. The latter launched the first of the genocidal campaigns against the Sikhs. After the Sikhs thwarted him, the governor decided to pacify them by offering a jagir (land grant) and the giving of the title of Nawab to the leader of the Sikhs.

The Sarbat Khalsa - or the gathering of Sikh clans -rejected the offer but they decided that the title of Nawab should be bestowed upon one of them who is beyond reproach. That person was Kapur Singh. Realizing that the offer from the governor was a trojan horse for future genocidal campaigns, Kapur Singh started organizing of the Sikh army into a unified force known as the Dal Khalsa. Indeed, the Nawab was correct. Zakariya Khan tried to take back the estate that he had granted. Under the leadership of Nawab Kapur Singh, the Dal Khalsa fought back; ultimately its leadership passing to the legendary Jassa Singh Ahluwalia. Nawab Kapur Singh was also responsible for creating the misls or confederacies which in a span of about 60 years repelled the murderous forces of the Mughals, then the Persians, and finally the Afghans-ultimately resulting in the sacking of Delhi by Baghel Singh in 1783.

Dr. Pannu judiciously sprinkles verses from the Guru Granth Sahib in his narrative to illustrate important spiritual precepts that flowed from his conversations with other mystics during his travels or Udasis. The story of the encounter with Mian Mitha is one such example. It is these vignettes that enliven this book. The author’s frequent references to people of significance and their place in Sikh history shows the depth of research that he undertook. And this colossal effort cannot be underestimated especially when one reviews his extensive bibliography.

That Dr. Pannu is not a trained historian should not in any way diminish his considerable efforts in analyzing the vast array of material that he has consulted. He has not shied away from delving into the nuggets of wisdom contained in the Guru Granth Sahib nor from examining contemporary sources. As such, he is able to give that rare glimpse through the cracks of history such that the record of the past is something which today’s lay historian can reveal and that something with which the average reader can relate. This is not an easy task and is one that Dr. Pannu has undertaken with considerable aplomb. This is not in any way to assert that the work of scholars should be underestimated. Recent work by Dr. Priya Atwal, for one, compels us to revisit the historical records to look at the influence of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s wives (Mai Nakian) in the administration of his affairs in Sheikahpura for example. Maharani Nakian deserves greater mention and perhaps will be honoured in some future edition. She was a formidable administrator the likes of whom enabled the sustenance of the empire of Ranjit Singh.

Of exquisite delight are the frescos that are shown at various Gurdwaras. They give much insight into the place of art in the depiction of the culture of the period surrounding their painting. The Gurdwaras at Chuian and Madhali, both in Khasur, are primary examples of the frescos. Even more splendid are those in the Dharmasala at Bhoman Shah, south of Lahore. Here a Sardarni leads the hunt-seemingly capturing a deer with her dupatta - while her husband rides his horse leisurely, presumably anticipating a lavish feast. The fact that a woman indeed leads a charge is significant in and of itself and puts to examination the nature of the male dominated society of that time. Indeed, with a discerning eye Dr. Pannu highlights the intriguing discoveries revealed by the artwork. He provides a glimpse of Hamza Gauz's tomb in chapter 18 (Gurdwara Babe di Ber). According to Sikh tradition, it was with Hamza Gauz, a well-known pir, that Guru Nanak held a discussion in Sialkot. The author draws attention to a simple-to-miss black-colored Ganesh Chakar inlay that is embedded in the red brick on the rear wall of the gurdwara-an inlay that depicts the meeting. The author's efforts to reveal the secret Sikh artwork paid off when a prominent British publication, "The Architectural Historian," included a photo from this book on its cover page in November 2020. This illustration depicts a scene with a cannon and numerous dead troops from chapter 37 (Madhali).

The story behind Gurdwara Janam Asthan Guru Ram Das in Lahore is noteworthy not only because of the reason why it was constructed (to honour the hometown of the fourth Guru which initially was the Dharamshala), but during the time of Maharaja Ranjit Singh at the behest Maharani Nakian it was reconstructed into a large Gurdwara. It is also fitting and consistent with the author’s desire that one day Punjab be restored to its rightful beneficiaries- Hindus, Muslins and Sikhs - that he mentions the Wazir Khan Mosque which is situated inside Delhi gate. Despite the mosque being a building of exceptional ornamentation, it bears the name of a governor who was highly sympathetic to the Sikhs. In fact, Wazir Khan reportedly tried to intercede on behalf of Guru Arjan when orders were given for his execution. It was Wazir Khan who convinced the Mughal Emperor Jahangir to release the Sixth Guru when he was imprisoned at the Fort of Gwalior. Lahore is also where Gurdwara Dera Sahib was built to commemorate the place where Guru Arjan died. The circumstances behind his arrest namely the treachery of Chandu Shah and the connivance of the guru’s uncle, Prithi Chand, are described in detail (indeed the pernicious role played by the minas or wicked ones is a constant theme in this book). These solemn events are juxtaposed with photographs of the exquisite dome of the Gurdwara; perhaps as a metaphor for the majestic beauty of how the Guru accepted his death so stoically.

It needs to be noted that remnants of wall paintings at the Gurdwara depict very colourfully a reverence for Guru Nanak. These paintings are important for they represent the emergence of Sikh art and show a sophistication that has hitherto been ignored or at least marginalized when historians recount the cultural development of the Sikh community.

Dr. Pannu delves into the various theories surrounding the execution of Guru Arjan. In this regard, the author parses the various theories adroitly. They vary from the offence given by the Guru-the purported support of Jahangir’s brother Khusrau (“neither very deep nor very extensive”); the increasing popularity of Guru Arjan as a result of his organizational abilities and the establishment of Amritsar as a centre of the Sikh community; and, from Jahangir’s perspective, the Guru’s perceived support of Sufi doctrines (shunned by Imperial india) by their insertion in the Guru Granth. The author weaves through the different metaphysical arguments amongst the various strands of Sufism as he tries to weigh the evidence as to which parties were responsible for the execution of the Guru. While such analyses might seem to be esoteric it is important because the martyrdom of the Guru plays such a strong part in the Sikh tradition and especially in the concept of martyrdom itself. As Dr. Pannu declares it is clear that Chandu indeed played a role in Guru Arjan’s execution, but precisely how, and what his favorable representation in the administrative circles was remains conjectural (pg. 241).

It is fitting that the author concludes his book with a chapter on Gurdwara Darbar Sahib. This site memorializes Guru Nanak’s settlement for the last 18 years of his life after his Udasis or travels through nine countries to engage in discussions with other religious orders and to spread his message as to the essence of Humanity and their Divine. It is here that Guru Nanak showed by practice how his philosophy was relevant. He emphatically declared renunciation of the ascetic life and demonstrated by example that what became Sikhism should be based on the life of the house holder – a life to be enjoyed in all its myriad trials and tribulations. The author relays the events of the later part of Guru’s life before his demise. Pertinent passages wisely chosen from Sakhis and the Guru Granth Sahib elaborate on his wisdom; imparted to travelers who came to seek his guidance.

In his typically understated and non-judgmental fashion, Dr. Pannu laments that the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib “can today be seen through binoculars across the Indian side of the international border. So, from a 10-foot platform built on the Indian side can a Sikh devotee claim reclamation of their birthplace of his or her tradition.”

Dr. Pannu’s metaphor of the buildings crying out for preservation in his introduction referred to above is one that should not be limited to just the Sikhs. These are remnants of a rich culture dating thousands of years; the product of a remarkable message of Oneness that sought to shed aside narratives based on ego and otherness. It is to this spirit that I think this author harkens and admirably summons our attention whether Sikhs or Pakistanis who currently reside in Punjab, Pakistan. The author truly hopes that one day Punjabis will unite and answer the mournful pleas of these glorious edifices. They were once the apotheosis of all that was the best in us.