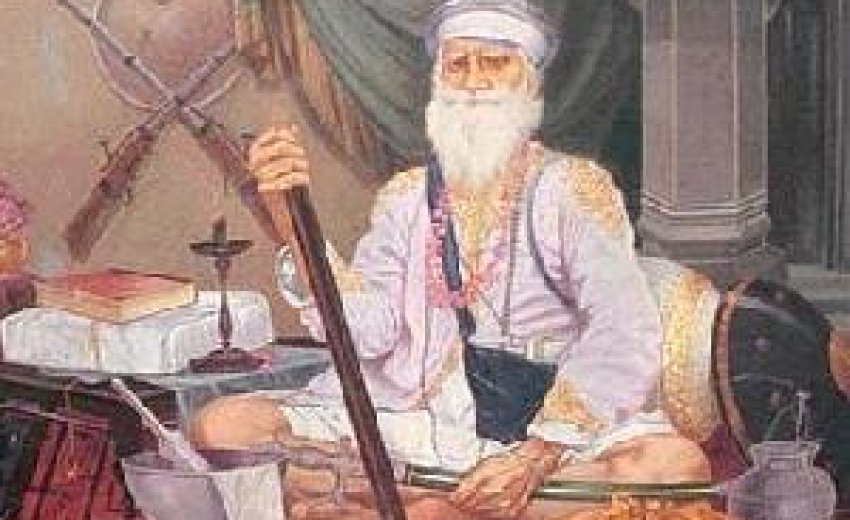

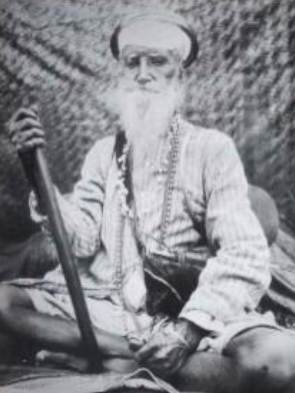

Bhāī Mahārāj

Singh was born into a Grevāl Sikh family in Rabbon in the district of Ludhiāṇā and was given the name Nihāl. Nihāl soon stood out due

to his deep piety which led him into Bhāī Bīr Singh's Ḍerā in Nauraṅgābād when he was still very young. Bhāī Bīr Singh had the

most eminent student of Bābā Bhāg Singh of Poṭhohār, who had wanted to return to the Gurūs' original

statements of the Sikh faith, and Nihāl in turn adopted this attitude.

Bhāī Mahārāj

Singh was born into a Grevāl Sikh family in Rabbon in the district of Ludhiāṇā and was given the name Nihāl. Nihāl soon stood out due

to his deep piety which led him into Bhāī Bīr Singh's Ḍerā in Nauraṅgābād when he was still very young. Bhāī Bīr Singh had the

most eminent student of Bābā Bhāg Singh of Poṭhohār, who had wanted to return to the Gurūs' original

statements of the Sikh faith, and Nihāl in turn adopted this attitude.

Nihāl spent many years of untiring Sevā in Ḍerā, always reciting the name of GOD. Every morning at three o'clock Nihāl Singh brought Bhāī Bīr Singh fresh water to honour him. The day came when he received Ammrit and his new name Bhagvān Singh from him.

Bhāī Bīr Singh's Ḍerā was a military base which comprised about twelve hundred warriors and three hundred horsemen.It was a centre of the resistance against the Ḍogrā's rule, offering refuge to all those persecuted by them. Among those, in 1844, were General Atar Singh Sandhāvālīā and Prince Kaśmīrā Singh, whose extradition Hīrā Singh Ḍogrā, supreme minister of the Pañjāb, kept demanding in vain. Finally Hīrā Singh Ḍogrā launched an attack with about two thousand soldiers and fifty guns. Hundreds of Sikhs fell in the ensuing carnage as well as General Atar Singh Sandhāvālīā, Prince Kaśmīrā Singh and Bhāī Bīr Singh. After the enemies' retreat Bhagvān Singh was appointed to be his teacher's successor, but only shortly afterwards he handed over the Ḍerā to a Sikh who was also called Bīr Singh and went to Ammritsar to create a new Ḍerā there.

Following the first Anglo-Afghan War (Auckland's Folly, 1839 to 1842), Bhagvān Singh stayed in Jalandhar Doāb to arouse the people there against the British.

In 1847 tensions arose between Mahārāṇī Jindān Kaur and the Brits, who wanted to deprive her of her power. This resulted in the so-called Premā plot which envisaged the murder of Henry Lawrence, the British envoy. But the plot, and Bhagvān Singh's role in it, were uncovered and the Brits had his property confiscated and declared him an outlaw. The British governor, General Lord Dalhousie, put a bounty of ten thousand rupees on his head. Bhagvān Singh went underground together with about six hundred of his followers, who called him Bhāī Mahārāj Singh as he became a holy warrior due to his resistance against the Brits. During this time Bhāī Mahārāj Singh also contacted Dīvān Mūl Rāj, Nāzim of Multān, to drive the Brits from the Kingdom of Lāhaur together with him. But in 1848 there arose an irreconcilable dispute between them, and Mahārāj Singh Jī left Multān and went to Hazārā.

In November 1848 Bhāī Mahārāj Singh joined Rājā Śer Singh's forces in the vicinity of Ramnagar. The records tell us that Bhāī Mahārāj Singh sat on a black horse and, at the risk of his own life, kept cheering the Sikh warriors on in their fight against the British. He also steadfastly remained at Rājā Śer Singh's side during the engagement at Ciliānvāl, but he dissociated himself from Rājā Śer Singh when Rājā Śer Singh surrendered to the Brits after his defeat in the battle of Rāvalpiṇḍī, on March 14, 1849. Bhāī Mahārāj Singh managed to escape to Jammū, where he made Dev Baṭālā his new base.

Henry Lawrence, the British envoy at Lāhaur, said this about Bhāī Mahārāj Singh:

"Bhāī Mahārāj Singh is a Sikh priest of great saintliness and great influence who in 1848 was the first to carry the flags of rebellion outside the borders of Multān, and he is the only important leader who did not lay down his arms to Sir Walter Gilbert in Rāvalpiṇḍī."

Bhāī Mahārāj Singh Jī wanted to free Mahārājā Dalīp Singh from his captivity in the Fort of Lāhaur at the hands of the British, but his plans were uncovered and Mahārājā Dalīp Singh was transferred to a safer fort. Again the Brits tried to get hold of Bhāī Mahārāj Singh, but they did not succeed. The people of Pañjāb stood behind their Bhāī Mahārāj Singh and helped him without flinching. The Brits' started calling him Karnīvālā – worker of wonders – to whitewash their failure to catch him.

Bhāī Mahārāj Singh's most ardent wish was to see all India free from British rule, and he therefore sought the help of the Mahārājā of Bīkāner, Dost Muhammad Ḳhān of Afgānistān and Mahārājā Gulāb Singh of Jammū and Kaśmīr. But again he was doomed to failure. The second Anglo-Afghan war, which began in 1848, led to the Pañjāb being annexed on March 29, 1849.

Many influential people in the district of Huśiārpur supported Bhāī Mahārāj Singh, and in November of 1849 he was able to finish his preparations for attacking areas in the Jalandhar Doāb. At a public gathering at Śām Caurāsī he proclaimed the twentieth day of Poh (January 3, 1850) as an auspicious date for the uprising. But again fate failed him and on December 28, 1849, the British arrested him near Ādampur. He was accompanied by twenty-one of his companions, all of whom were unarmed.

Henry Vansittart, the Deputy Commissioner of Jalandhar, who had arrested Bhāī Mahārāj Singh Jī, wrote about him:

"The Gurū is no ordinary man. He is to the natives what Jesus was to the most zealous of Christians. His miracles were seen by tens of thousands, and are more implicitly believed than those worked by the ancient prophets."

Henry Vansittart was so deeply impressed with Bhāī Mahārāj Singh Jī that he personally contacted the British government to plead for preferential treatment for him, but his efforts fell on deaf ears. As the British were afraid of popular outrage and did not want to take any risks, they deported Bhāī Mahārāj Singh and his steadfast companion Khaṛak Singh to Siṅgāpur. They arrived there on July 9, 1850 onboard the Mahomed Shaw and were taken to the Outram Road prison. On this day Bhāī Mahārāj Singh's inconceivable martyrdom began.

As the cell door thunks shut behind Bhāī Mahārāj Singh Jī, his eyes see with a shiver what his mind cannot grasp yet – that he has been condemned to solitary confinement in darkness* What he does not know is that the windows of his tiny cell* have been bricked up especially for this purpose. From now on eternal night without even flittering shadows will be around him. All of his days and nights, tomorrow as well as yesterday, will be one. Time has ceased to exist. Feeling his way like a blind man, Bhāī Mahārāj Singh moves around the pitch-black cell. His feet feel old rubbish underfoot – even he is not worthy of this. Bhāī Mahārāj Singh will never again have any companion save for fleas and cockroaches and perhaps a rat. The life left to him is his own living death. The black night around him starts to feed on Bhāī Mahārāj Singh. After three years in this hellhole he is as good as blind. When the civilian physician advises the representatives of the British government to at least allow Bhāī Mahārāj Singh to take a walk in the sunlight now and then, they refuse – forgetting that the Christian Bible says

…HE causes his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust…(Mathew 5: 45)

In addition to Bhāī Mahārāj Singh Jī's blindness, his feet and ankles start swelling with rheumatism. The last outcry of his soul is a cancer of the tongue. But all this does not move the Brits, who imagine themselves to be the representatives of law and justice.They are blind and diseased with hatred for this man who dared demand freedom for his country and whose sentence is out of all proportion to his crimes. And Bhāī Mahārāj Singh's martyrdom is to drag on for a further three endless years.

VĀHIGURŪ JĪ, how long does eternity last?

About two months before his soul can leave his body, Bhāī Mahārāj Singh's throat and tongue are so swollen he can hardly swallow.

VĀHIGURŪ JĪ, have mercy.

Every day has its colour. July 5, 1856 is the last day that came into Bhāī Mahārāj Singh Jī's downtrodden life, horrified at seeing a fatally ill man, covered in filth and emaciated, hearing his rattling breath and his groaning with pain. But maybe July 5, 1856 then also saw this:

The shimmering light that suddenly illuminates the black cell and the man with a crown of thorns and wounds on his hand and feet, who sits down next to Bhāī Mahārāj Singh and compassionately and puts him on his lap, like his mother Mary once put him on her lap,and then his tortured cry:

"FATHER, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing." (Luke 23: 34)

Blood flows from Christ's wounds, which have been torn open again, and he is nailed to the cross once more.

After that, July 5, 1856 sees the woman with the sad eyes who kneels down next to Bhāī Mahārāj Singh and gently strokes his feverish forehead. Before she can say anything, stammering words come from his cancer-ridden mouth:

"M…M…Moth…er," for the mother's gentle hand is never forgotten.

"My poor child, what have they done to you…"

"M…M…Moth…er."

"I am here, my dear son. I will take you to a star where all your suffering has ended and where the sun always shines so bright, so bright, and bathes blossoming meadows in glowing tales of spring. And the birds sing their gentle tunes."

"M…Moth…er, o yes, dear...dear mother...", and seeing with the inner eye, suddenly the mother's eternal child cries out in a clear voice:

"Mother…Mother… look, look…Gurū Nānak…"

July 5, 1856 sees Bhāī Mahārāj Singh entering obediently into VĀHIGURŪ JĪ's aureole and retains all this in its heart in awe.

Bhāī Mahārāj Singh Jī was cremated on a plot of land outside the Outram-Road prison, probably by Khaṛak Singh, who also died in this prison later. The local people, mainly Tāmils, began to revere the spot of his cremation, erecting a small wall of stones around it and offering flowers. Muslims and Sikhs joined in, with the Sikhs later on building a small Gurdvārā called Silat Road Temple in honour of Bhāī Mahārāj Singh, one of the first freedom fighters against the British. In 1966, the Śrī Gurū Granth Sāhib Jī was installed there.

*. Author's remark. The cell was 14 feet by 15 feet, about four meters by four meters and fifty centimetres

~ This story is copyright 2013 by Elisabeth Meru