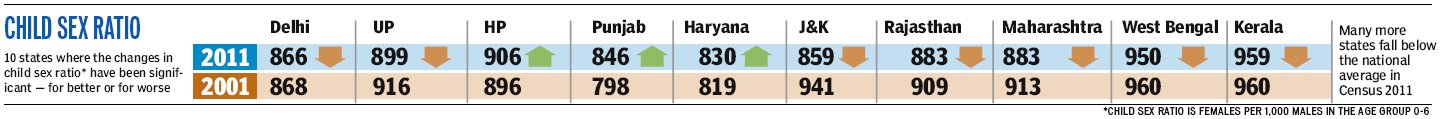

GROUND REPORT India's child sex ratio has dropped from 927 to 914 girls per 1,000 boys according to Census 2011.

To understand the problem, HT travels to districts in 4 states, each of which present a different scenario - either displaying remarkable improvement or

decline from 2001

THE BEST PLACE TO BE A

GIRL CHILD...

ON THE RISE ON THE RISE

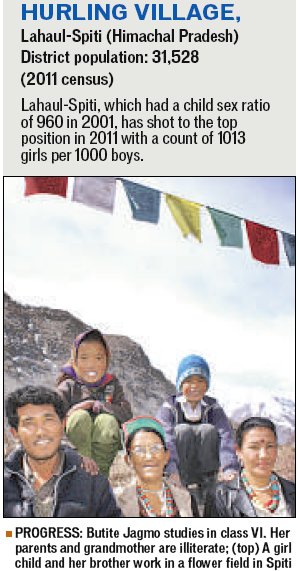

HIMACHAL DISTRICT EMERGES TOP SCORER

Govt cracks down on pre-natal tests

Aasheesh Sharma

º [email protected]

The village is under a thick white blanket. Hurling gets cut off from the rest of India every time it snows. And for the past three days, it has snowed heavily in the upper

reaches of Spiti, Himachal Pradesh.

So, the news that Lahaul-Spiti has

topped Indian districts with a child sex

ratio of 1013 works like an icebreaker.

"Really?" exclaims Yeshey Dolma, who

teaches in the village school. "I didn't

know this. And how would we know?

No newspapers reach Spiti between

October and May."

NS Bist, Professor, Himachal Pradesh

University, who specialises in demography

and population studies, says

women, who work in the fields, are the

family's mainstay.

"Cultivation in the

tribal districts of Lahaul, Spiti and

Kinnaur is carried out by women

between April and November. Also, for

the last four years, the government has

implemented the Pre-Natal Diagnostic

Techniques Act more forcefully. This

has reflected in Census 2011."

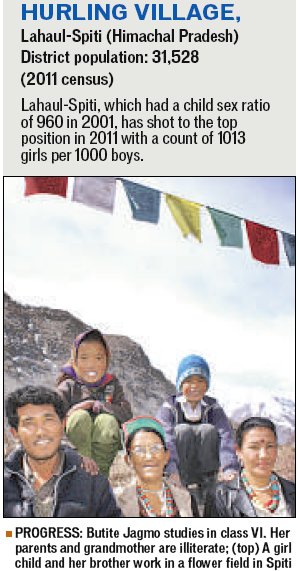

Butite Jagmo, 11, one of Dolma's students,

hasn't just out-studied her fifthclass

dropout dad Chunni Lal, but her

unlettered mother and grandma as well.

Butite's mother wasn't allowed to attend

school. "I was made to cultivate rice

instead. I have ensured it doesn't happen

to my daughter," she says.

At the senior secondary school in

district headquarters Kaza, 25 km from

Butite's home, in subzero conditions, a

group of girls is sweating it out on the

basketball court. "They are my powerpuff

girls: they always beat the boys at

studies and sports," says their history

teacher Dikit Dolker.

At home, the boys have it easier.

School or no school, girls begin their

day cooking rice for the family, says

Nawang Dumgzo, a Class X student. "I

then wash the floors and fetch water

as the pipes get frozen. After school

between 10 am and 4 pm, I return and

again cook dinner," adds Dumgzo. "All

that boys do is while away time playing

or watching cricket," she says.

Since the last Census in 2001, people

in Lahaul-Spiti have realised that

the "sincere" girls also take better care

of their elders, says sociologist Sonam

Angdui, from Spiti's erstwhile royal

family.

"Boys take to drinking in their

teens, drop out and become taxi drivers

or construction contractors. By the

time they are 40, they turn into alcoholics."

Religion also affects the region's

demography, says Kishore Thukral,

author of Spiti, Through Legend and Lore.

Between 700-800 monks inhabit Spiti's

Kee, Tangyud, Dhankar, Tabo and

Kumgry monasteries.

Most villagers

send one of their children to embrace

monkhood. "Which could be why

Lahaul-Spiti's population hasn't grown

as rapidly as other districts," says

Angdui.

In the 2011 Census, the population of

Lahaul and Spiti actually dropped from

33,224 in 2001 to 31,528 in 2001.

Celebrated agricultural scientist MS

Swaminathan says Spiti's arid

weatherand the capacity to keep seeds

dry is ideal for multiple crops. "If we

develop its marketing potential the

district can turn into another

Switzerland," he says.

Much before Swaminathan, a

certain Rudyard Kipling praised Spiti

with these words in the classic Kim:

"Surely the Gods live here…This is no

place for men."

He could well have been talking about

the age of the girl child. |

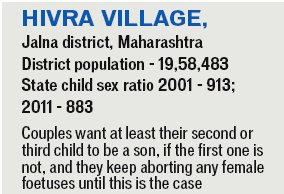

Everyone wants a boy

Prachi Prnglay

º [email protected]

In her thirties, Sunita admits that

she has undergone two sex determination

tests and then two abortions

when she found out she was

pregnant with girls. The boy came

after the two abortions. "We needed a

son who can look after us when are old,"

the housewife married to a farm labourer

in Hivra village in Jalna district of

western Maharashtra, 335 km northeast

from Mumbai. In her thirties, Sunita admits that

she has undergone two sex determination

tests and then two abortions

when she found out she was

pregnant with girls. The boy came

after the two abortions. "We needed a

son who can look after us when are old,"

the housewife married to a farm labourer

in Hivra village in Jalna district of

western Maharashtra, 335 km northeast

from Mumbai.

Records at the nearest primary

health centre show that in the past year

only 239 girls were born in 17 surrounding

villages, compared with 349

males. The child sex ratio in the whole

district has dropped to 847 girls per

1,000 boys, the 2011 census has revealed,

from 904 girls in 2001.

Activists say that the practice of

women undergoing sex determination

tests is widespread in this and other

villages of Jalna, a largely agricultural

district. The long-standing factors driving

this trend arise from the social system

entrenched in this village, as in millions

of others in the country: one in

which only men inherit property, carry

forward the family name, execute all

rituals, receive dowry from their wives

and are supposed to look after their

parents. More recent factors are the

easy availability of sonography

machines and an increasing awareness

about family planning.

"In the past, women could keep trying

for a son," says Kirti Udhan, chairman,

Jalna Zilla Parishad. "So you would

see women bearing seven to eight daughters

before finally giving birth to a son.

Now because of economic compulsions,

couples want at least their second or

third child to be a son, if the first one is

not, and they keep aborting any female

foetuses until this is the case."

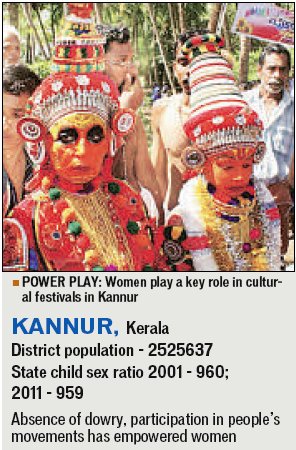

STILL GOOD IN KERALA, NUMBER

OF GIRLS HIGHER

THAN THE NATIONAL

AVERAGE

Sucheth PR

º [email protected]

Any imbalance in sex ratio is a

disturbing fact. But when the

number of girls exceeds that of

boys, it says positive things

about the social fabric. The politically

vibrant Kannur district of Kerala has

topped the sex ratio in the country as

per the 2011 census. Kannur has a sex

ratio of 1,133 females for 1,000 males,

much higher than the national average.

What contributed to its gender balance?

Kannur's long history of people's

struggles for social justice, the freedom

struggle and the Communist movement

that encouraged female initiatives in

social issues - all played their part.

"Rearing up girl children and giving

them in marriage is less expensive in

this region compared to other parts of

the state," says Professor Lakshmanan,

former director of KILA (Kerala

Institute of Local Administration).

The legacy of the female rulers of

Arakkal, the sole Muslim dynasty of

Kerala is still inspiringly alive in the

social memory of the district. Bibi

Harrabichi Kadavube ruled Kannur

during the first half of the eighteenth

century. The last ruler of the kingdom

was also a woman - Ali Raja

Mariumma Beevi Thangal.

The girl child was also supported by

its culture industry. Indulekha, the first

novel in Malayalam authored by

O.Chandu Menon was published from

Thalassery, a major town in Kannur

district known as the cultural capital

of north Kerala. The novel presents a

bold female character who challenges

the patriarchal Brahmanical hegemony

while the hero of the novel,

Madhavan, is feeble in attitude. The

total absence of the burden of the dowry

system among the Hindu community,

here, is a pivotal factor in the welcome

the girl child gets at birth.

The writer is a research scholar |

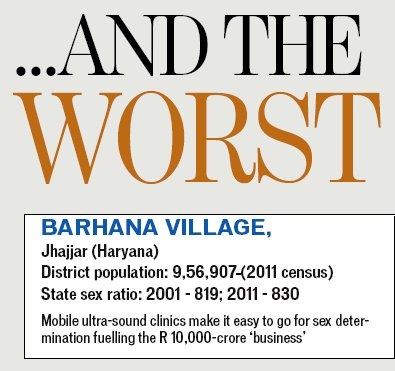

HELL- HOLE JHAJJAR RANKS BOTTOM IN CHILD SEX RATIO

Too macho to have a girl child

Praveen Donthi

º [email protected]

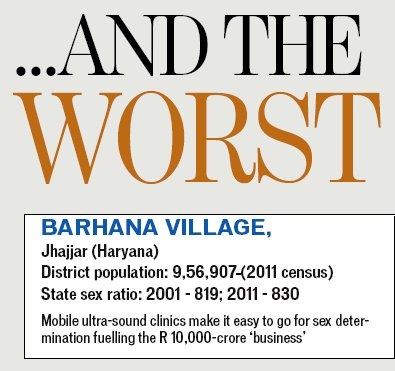

Pardeep (25), the popular sarpanch of Barhana, is a reluctant bachelor. The resident of a state that has the country's worst stats in sex ratio with 830 women per 1,000 men - Jhajjar is its worst district at 774 - he is finding it difficult to find a girl to marry. Barhana is Jhajjar's worst case - in 2010, there were 203 births - 148 boys and 55 girls so the sex ratio of this village with a population of 8,890 is 378.

The reason for not being able to find a bride is because there is less land left in the village, says Pardeep. Bhaarat Singh (53), Chief Medical Officer, Jhajjar, has his reasons for the sex ratio skew:

a) The 2003 amendment of PNDT Act, 1994, that allowed mobile ultra-sound clinics making it easier for sex determination b) PNDT Act not being under CrPC makes it easy for guilty doctors to get away c) Governmental promotion of 'small family' that encourages people to go for sterilisation if the first-born is a son.

BS Dahiya, former director general of health services of the state, who takes the credit for booking the first case under PNDT Act, says, "it's all happening because it is a R 10,000- crore business."

CMO, Jhajjar, also cites regional machismo as the reason for the decrease in girl children. "Because it is dominated by the martial races, there is the tendency to have more sons."

The imbalance in sex ratio has triggered many social and cultural problems. Brides are being brought from other states but many run away. The crime rate has gone up too. "There have been 2 to 3 rape cases per month," says Singh. The increasing crime in turn is "discouraging" them from having a girl child many claimed during the interview.

|

Any imbalance in sex ratio is a

disturbing fact. But when the

number of girls exceeds that of

boys, it says positive things

about the social fabric. The politically

vibrant Kannur district of Kerala has

topped the sex ratio in the country as

per the 2011 census. Kannur has a sex

ratio of 1,133 females for 1,000 males,

much higher than the national average.

Any imbalance in sex ratio is a

disturbing fact. But when the

number of girls exceeds that of

boys, it says positive things

about the social fabric. The politically

vibrant Kannur district of Kerala has

topped the sex ratio in the country as

per the 2011 census. Kannur has a sex

ratio of 1,133 females for 1,000 males,

much higher than the national average.

ON THE RISE

ON THE RISE In her thirties, Sunita admits that

she has undergone two sex determination

tests and then two abortions

when she found out she was

pregnant with girls. The boy came

after the two abortions. "We needed a

son who can look after us when are old,"

the housewife married to a farm labourer

in Hivra village in Jalna district of

western Maharashtra, 335 km northeast

from Mumbai.

In her thirties, Sunita admits that

she has undergone two sex determination

tests and then two abortions

when she found out she was

pregnant with girls. The boy came

after the two abortions. "We needed a

son who can look after us when are old,"

the housewife married to a farm labourer

in Hivra village in Jalna district of

western Maharashtra, 335 km northeast

from Mumbai.