ET Bureau | 2 Aug, 2013 - CHANDIGARH: Two small cars—a Hyundai Santro and a Maruti 800—are parked in the porch outside the elegant white three-storeyed house located in a sleepy Chandigarh colony, where neighbours, typically, are retired judges, bureaucrats or lawyers.

ET Bureau | 2 Aug, 2013 - CHANDIGARH: Two small cars—a Hyundai Santro and a Maruti 800—are parked in the porch outside the elegant white three-storeyed house located in a sleepy Chandigarh colony, where neighbours, typically, are retired judges, bureaucrats or lawyers.

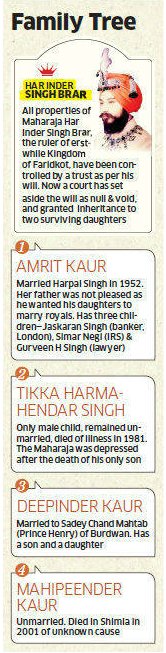

Inside, 80-year-old Amrit Kaur complained that the third power cut of the day was underway, as she sat down to discuss, reluctantly, her childhood, her father, the erstwhile ruler of Faridkot, and the epic two-decade legal battle that has won her rights to half of her father's property—estimated to be worth in all about $3.5 billion, or Rs22,000 crore. She gave ET the first interview after becoming India's newest billionaire.

"I knew from day one that we would win the case. I never had any doubts about that," Kaur said. If she was excited about the verdict that made her a billionaire overnight earlier this week, you couldn't tell from her manner. She spoke in English, mostly limited her responses to a line or two, and smiled only when she was asked about her grandchildren or her childhood. She didn't hide her unease with references to the money or questions about how she met her husband, who she married in 1952 against the wishes of her father—a point that the defence lawyers hammered on during the trial to argue why the Raja had left her out of his supposed will.

The property in question is very substantial. It includes marquee properties in five cities, including two large bunglows in Lutyen's Dehi, forts, palaces, a private forest and Himalayan hillsides, private airstrips and agricultural land, arms, antiques and jewel boxes that have lain unopened in bank lockers for decades. The value of the property is hard to estimate accurately, and the family alleges that many valuables have disappeared from the properties over the years. They also suspect that some of the property has been sold off by the trust that has been controlling the estate.

Kaur has lived with the knowledge that she has been defrauded, for 24 years—since her father's death in 1989. That is when a will surfaced, giving control of all his property to a trust that accommodated her two younger sisters and gave effective control to a small group of men comprising of her father's advisors and employees.

"My father was a very loving and caring man towards all of us. I knew he could never write such a foolish will," she said.

"My father was a very loving and caring man towards all of us. I knew he could never write such a foolish will," she said.

The fondest memories of her childhood, spent at the Faridkot palace and the family's summer retreat in Mashobra, is of her father flying her to Delhi in his two-seater planes. He was an avid aviator and owned six aircraft at one point, and private airstrips. "He taught me to play bridge, he taught me ballroom dancing, and he taught me how to drive. I learned in a two-seater Bantam car," she said. "He loved to play bridge, and he loved to entertain, which he did a lot."

While her father did not approve of her marriage to Harpal Singh, a police officer who was employed by the Maharaja, she says he came around later. Singh later joined the Indian Police Service and rose to become the DIG of Haryana and a decorated officer, winning the President's police medal for distinguished service.

"I think it is fair to say that the Maharaja was not excited about his daughter marrying a commoner," Singh, now 91, said. "But could you please avoid personal questions?"

The couple, now married for 61 years with three children and three grandchildren, declined to discuss how they met or how they courted away from the stern eyes of the Maharaja.

From the numerous letters that the Raja wrote to his daughter and son-in-law in subsequent years, it is clear that he had moved on. The trial judge also relied on the correspondence to dismiss the defence argument that the Raja nursed resentment towards Kaur as she married an employee. The correspondence also suggests that the Raja enjoyed his drink. Many letters to Singh, who was serving in the Border Security Force at the time, ends with requests for bottles of rum. In the letters, the Raja always addressed his daughter as "My dearest sergeant" or "My dearest Cuckoo" and to Singh as "My dear Sardar Harpal Singh".

The protracted case

It was at the Bhog ceremony of the Raja after his death that an advocate announced the existence of a will. Kaur says she immediately suspected foul play. The will named a board of trustees and a board of executors. Curiously, the board of executors, comprising of his advisors and lawyers, exercised full control over important decisions of the trustees, including final say in the appointment of trustees. Deepinder Kaur, the Raja's second-youngest daughter, was named the chairman and his youngest daughter Mahipeender Kaur was named vice-chairman. Both would get a salary—Rs1,200 per month and Rs1,000 per month, respectively. Amrit Kaur was excluded from the will. Deepinder Kaur had married as per the Raja's wishes into a wealthy landowning family of Kolkata—the Mahtabs of Burdwan.

Amrit Kaur says that her younger sister, Deepinder Kaur, became a pawn in a larger game by her father's "servants", who conspired to usurped his property. Does she have hard feelings against her sister. "Now I'm starting to have hard feelings," she said.

Kaur moved court in 1992 against her sister, the trust and its administrators, arguing that her father's will had been forged and she should inherit his property in the absence of a valid will. The Raja's only son, Tikka Harmahendar Singh, had died of illness in 1981. Subsequent to his only son's death, the Raja is said to have gone into depression.

Mahipeender Kaur, who was named vice-chairman of the trust, also soon turned against the arrangement, and had moved court arguing the will was forged. She was allowed two rooms in a house in the Mashobra estate. Amrit Kaur's family says she was ill-treated by the trust administrators. Once when Amrit Kaur's daughter Gurveen H. Singh went up to visit her aunt in Mashobra, she was not allowed to enter the premises.

While Mahipeender's case against the trust was in the court, in fact on the very day she was to appear for a hearing in 2001, she passed away. The case lapsed away due to non-appearance. Amrit Kaur's family says the circumstance of her death is "mysterious". She had not married.

There were fire-related incidents in three of the five Mashobra bunglows of the Raja's estate. Kaur says all the valuables in these houses, including vast libraries and paintings, have disappeared. She also suspects that the fire was not an accident. "Nothing surprised me. These people were there for looting. Not to propagate the estate," she said.

After a lengthy trial, Additional Civil Judge Rajnish K. Sharma found merit in Kaur's argument and set aside the will as null and void. With the judgment, the existence of the trust has become illegal.

Trust's spokesperson Wahniwal said no property has been sold off by the trust and that it would appeal against the decision. "We have been denied justice. The decision is against the law. We will go for appeal," he said. Deepinder Kaur could not be reached, but trust officials said Wahniwal spoke for her.

Deepinder Kaur also stands to benefit massively from the judgment, which divides the property equally among the two surviving daughter's of the Raja as per the Hindu Succession Act. The case can now either go into a lengthy loop of appeals or the two sisters can reach a settlement on how to divide the property.

The judge found the erroneous spellings in the will, the fact that the attesting witness was a relative of a beneficiary, the circumstances of the discovery of the will and several other discrepancies as sufficient ground for setting aside the will as illegal.

Outside interests?

Kaur says she hasn't decided what to do with the money. "I will think about it when I get the money." She says her life wouldn't have been very different if she had had the money all along. "We had everything we needed. My children went to the best of schools and colleges. I have traveled the world. We are comfortable," she says, appearing somewhat confused about what the fuss was about.

Curiously, she had entered into an agreement in 1996 with a third party, transferring to them 80% of the costs and benefits of the case for a consideration of Rs.65 lakh. As per the agreement, technically called an "assignment deed", a copy of which ET has seen even though this newspaper could not establish its authenticity, a group of nine men from Ambala, represented by one Satpal Grover, had paid Rs65 lakh through two demand drafts to Kaur. When she was asked about this agreement in court by the defence lawyer, she said she had indeed entered into such an agreement, but the agreement did not stand. She said she had spent the money to pay lawyers in the case.

"It appears from this agreement she entered into in 1996 that there are other people who are interested in this litigation," Wahniwal said.

The agreement, however, was not a factor in the adjudication and it does not figure in the judgment. Kaur's daughter Gurveen Singh there are no other claimants to the inheritance and there is no agreement that is standing. "My mother has done nothing that is incorrect, unethical or illegal," she said.

Kaur says she is happy that her children and her grandchildren will benefit from the money that has been illegally denied to her. All her grandchildren congratulated her on the phone on her legal victory, she said, smiling.

Kaur is not about to make any lifestyle changes on account of the new billions in her bank, even when it actually gets there. For one, she doesn't plan to move from the Chandigarh house her husband built in 1968 and where the couple has lived since his retirement in 1980.

"I will visit all the properties of my father where I had not been allowed. But I'm not going to live anywhere else," she said.