The lives of Sikhs and Christians in Pakistan

|

|

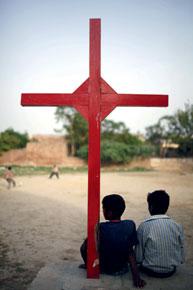

| STATE SUPERVISION The Pakistan government keeps control of Sikh shrines through the Evacuee Property Trust Board, which also manages Nankana Sahib (Photo: JATIN GANDHI) | LONESOME SILENCE: A Christian Colony in Lahore, Pakistan |

LAHORE/NANKANA SAHIB ~ If his turban were tied differently and not like a Sikh’s, I would never have guessed Amir’s religion. With his long flowing beard, he could pass off as a Pashtun from either Pakistan or Afghanistan, or even a well-built Hazara, at least for someone like me. Not just because of his outfit—a flowing salwar kameez—but because of the way he speaks. Even his name is misleading. Amir is a popular name among Pashtuns and means ‘sovereign’ in Arabic, a language once alien even to the Pashto-speaking regions of modern-day Pakistan that border—and are not too clearly demarcated from—Afghanistan. But that was a long time ago, and there was no Pakistan then. We do not have a language to link us either. Amir speaks only Pashto. Even though he works at the Nankana Sahib Gurdwara—among the most revered by Sikhs because Guru Nanak was born here—he does not understand either Punjabi or Gurmukhi, the script in which the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy book and ‘living Guru’, is written.

Pashto, says Amir, is his mother tongue. He says this through an interpreter who translates his words into Punjabi for me. Amir has not bothered learning Punjabi since he has always harboured hopes of returning to his home in Kurram Agency in FATA (the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Northwest Pakistan marked out by a disputed Durand line). He is 65 years old, and frankly, it seems to me that he has decided not to pick up another language even if he cannot go back; that he will get a chance seems unlikely under the current circumstances.

As an aging Sikh with a Pashto-speaking Sikh mother, his family and immediate ancestors must have lived in Kurram for a long time before their departure. He does not know how long. He had never bothered asking anyone, he says. However, it is believed that Sikhs settled in those regions in the early 19th century, at the time that Maharaja Ranjit Singh established his Sikh Empire with Lahore as headquarters—the famous Lahore Durbar. The possible story of his lineage had not occurred to him. Kurram was home and that’s all. The Sikhs there were distinct from the Pashtuns around them, but co-existence was a way of life. Amir’s family had moved to Hangu (a region carved out of Kurram Agency closer to Punjab but still in FATA) in the past and then to Peshawar about ten years ago. Today, Peshawar is out of bounds for them, he says. It is not as if there are no Sikhs there anymore, it is just that most departed once the Taliban tightened its grip, some sooner than others. Those who stayed on have had to pay a heavy price—kidnappings, extortion and even killings.

Amir says he ran a store of daily household items in Doaba village, but had to leave with his family after the “Taliban’s grip tightened”. He uses this phrase again, jerking both hands together to suggest suffocation. I ask the interpreter to ask him if it was like a ‘noose’. Once my question is posed, Amir and his other Pashto-speaking compan-ion Hukam Singh crack a joke. Perhaps they are making fun of the question; or perhaps they are happy to have escaped the noose. Either way, the answer is lost in translation.

+++

Since 9/11, nearly 200 families of Hangu and Kurram have moved to Nankana Sahib. Hukam Singh, closer to Amir in age but comparatively better built, moved here three years ago. His village was further away from Kurram agency, closer to the porous border. “The Taliban had started asking non-Muslims for jaziya (tax). It was first Rs 3,000 for a shop, which we would pay, but their demands increased,” Hukam Singh says. The options that the Taliban offered the area’s Sikhs were grim—conversion to Islam or paying large sums of money collectively as a group. As more and more Sikhs left, it was impossible for the few who remained to fulfil the demands.

The interpreter, Kalyan Singh, is Sikh too. By his voice and manner, he comes across as the sort I am used to meeting in Delhi. That is because Kalyan was born in Nankana district and grew up here among Punjabi speakers. He is now a Punjabi teacher, an assistant professor at Punjab University’s Gujranwala campus. He is also a PhD scholar in Punjabi literature. His topic of research: ‘Guru Granth Sahib: A Philosophical Treatise on Communal Harmony.’ Ironically, the script in which he will submit his thesis is not Gurmukhi but Shahmukhi—Punjabi written in the Urdu-Persian script. It is not merely Gurmukhi that is endangered here. Shahmukhi is fast disappearing too. Kalyan is home these days because Eid is approaching and the campus is shut for the festival. He can get along fine in Pashto, but he is mostly a Punjabi speaker it seems. He is equally at ease in Urdu.

All three men, of different generations, are refugees in a certain sense of the word. Kalyan is 32 years old. His parents moved to Nankana Sahib after the 1971 Indo-Pak war in which India aided the formation of Bangladesh and the Sikhs of Wadiye-Terah in Khyber Agency bore the brunt of West Pakistani ire. It was Pashtuns who pushed Kalyan’s family and several others out. Those who stayed back were killed, he says. Terah valley was in the news in February 2010, when Taliban fighters abducted three Sikhs from there and beheaded one, Jaspal Singh, for refusing to convert to Islam. His head was sent to Peshawar’s Gurdwara Joga Singh, which had re-opened in the 1980s after staying shut for a long time. The incident led many Sikhs to flee Peshawar and seek refuge in Nankana Sahib. That is when Amir came here with his wife and three sons.

The children, the youngest of them a teenager, did not attend school. In fact, Kalyan is among the few young men here with an education. The local Government Guru Nanakji High School was an Urdu medium school till 2009. Local Sikh children who finish school rarely venture further. The circumstances that brought these refugees to Nankana have been different, but their exodus pattern and the monotony of their lives here are strikingly similar. If Hukam Singh came here after the 11 September 2001 attacks in the US, about 50 families had arrived here from different parts of Pakistan after the 6 December 1992 demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, India. Refugees account for more than half the Sikh population of roughly 3,000 in Nankana district.

Hazmat Singh arrived eight years ago after the murder of the Baloch tribal leader Akbar Bugti during General Musharraf’s regime. The killing sparked ethnic violence and led to a wave of Sikhs and Hindus fleeing the area. Hazmat, who speaks broken Punjabi, earns Rs 5,000 a month at the Gurdwara and has a family of seven to support. The children get to eat at the Langar (community kitchen), but they do not go to school. “It costs Rs 4,000 per year to send one child to school,” he says, and informs me about a pilgrim who came here last year from Canada and gave him enough money to send his youngest son to school for two years. Hazmat did not. Instead, he says, he used the funds to raise the children. He is not sure if he will come across another donor among the Sikh pilgrims who converge on this revered shrine.

Most of the men here work at the Gurdwara as sevadars (helpers) and earn a few thousand rupees each every month, which is never enough to make ends meet. Some are employed in the shops of earlier settlers who run small businesses. Kalyan’s father, who runs a store in the market outside the shrine premises, is a member of the Pakistan Sikh Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (PSGPC), the country’s Sikh shrine-managing body.

It took him decades in Nankana to attain such a stature and the wherewithal to send his son to college. But then, compared to the cash-rich and politically powerful SGPC in India, the Pakistani equivalent is a poor cousin. Even the state of the shrine here presents a sharp contrast with the Golden Temple in Amritsar, or for that matter any other prominent Gurdwara across the border. The SGPC in India, more so in Punjab, runs not just Gurdwaras but also Sikh religious affairs. The ruling Shiromani Akali Dal in Punjab has never let the SGPC out of its sight because that would mean losing influence over a lot of Sikh votes. In Pakistan, the government exercises control over the few Sikhs there are, an estimated 50,000 or so scattered across the country, largely through the Evacuee Property Trust Board (EPTB), which manages the shrine. Among local journalists—since I am part of a delegation of journalists from India hosted by Lahore journalists, there is plenty of information being exchanged—it is common knowledge that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence keeps a close tab on the EPTB’s operations. The PSGPC’s term is over and elections have been due for months now, but are yet to be held.

Malik Anwar, district in-charge of the EPTB, clad in a sparkling white salwaar-kameez as he plays host to the visiting delegation, talks of taking “Sikhs along”. He sounds like a politician. “It is important to keep Sikhs involved in the management of the shrine so that we do not make mistakes out of ignorance [of their practices],” he tells delegates, “Sikhs have businesses in town, they live like Muslims here.” Clearly, the PSGPC reports to the EPTB, and Anwar lords over its affairs. His men, clad likewise in white, keep a close watch on who’s talking to which visitor and about what.

At the Gurdwara Dera Sahib in Lahore, a similarly clad official comes and stands next to me while I have a conversation with 17-year-old Mahinder Pal Singh, a first year pre-medical student of Lahore’s Government College. He has got this far because he opted out of the local Urdu medium school and joined the English-medium Al Muarif Higher Secondary School. He secured admission through a 5 per cent quota in colleges for minorities. He has been provided free accommodation by the Gurdwara; it has over 30 rooms for Sikh students who need a place to stay in Lahore to pursue higher education. Only three are occupied. He has barely begun talking about the difficulties of his friends in seeking admission under the quota when the man in white appears. “It is Allah’s grace that Sikhs and Hindus are treated so well in Pakistan,” says Mahinder Pal suddenly, alerting me to the intruder’s presence.

I move into the kitchen, where I meet Pritam Singh, a cook who was a cloth merchant in Dadu district, Sindh, and moved to Lahore five years ago. He does not make a merchant’s money as he once did, he says, but his family feels safe.

+++

By official statistics, Muslims are 96 per cent of Pakistan’s population; Hindus and Christians together form about 3.2 per cent, and Sikhs, Parsis, Jews and others the rest. Before setting out for Lahore in late October, I had contacted a minority rights lawyer there to help me meet Sikhs and Christians in the city. There had already been a flurry of reports on Hindus crossing over to India from Pakistan with valid visas but refusing to go back, and I wanted the stories of non-Hindu Pakistani minorities.

The lawyer put me in touch with an activist who has worked with Christians. She has come over to my hotel in Gulberg, a leafy locality of Lahore, to meet the other visiting journalists, but is reluctant to let me meet Christians in her office. She promises to arrange visits to some Christian homes instead.

“I just want to know how they live in Pakistan,” I tell her. “The way Muslims live in India,” she says, advising caution, “These are sensitive matters. A report can give an opportunity to communal forces to derail the peace initiative.” Those are her exact words. ‘Derail’, ‘peace’, ‘initiative’. The promised meeting never happens.

So I begin searching for Christians on my own. A journalist at the local press club tells me to search among the sweepers in my hotel. On the second day of my search, I meet Sham Masih. He has been around all along. Only, the other housekeeping boys, his colleagues, do not know that Sham is Christian. “I never let anyone feel I am not Muslim,” says Sham, “I keep myself clean and I dress well, by Allah’s grace.”

Sham has never been to school. Nor have his siblings. But he earns well, Rs 9,000 a month, of which he gives Rs 500 to St Paul’s Church in Green Town, nearly an hour’s drive from Gulberg. There is a bigger cluster of Muslim homes in Raiwind further away from the city towards Kasoor. Sham says he mingles with people of his community on Sundays, but his friends are mostly Muslims, “by Allah’s grace”, he repeats. He faces trouble for not being Muslim, he says, only when he is found out. “Then they say I should convert, they don’t want to break bread with a non-Muslim. But I usually never let anyone know I am not Muslim,” he says and leaves.

The brief meeting has left me and my roommate Rahul Puri silent. The door is still open. Sham has returned. He asks if I can spare him a few cigarettes. I offer him an open packet. He takes four sticks and says, “Allah hafiz” with a big smile as he shuts the door behind him.