|

In this second article highlighting the earliest Americans to visit the Golden Temple, Parmjit Singh uses images and extracts from his latest book to recount the intrepid 19th-century New Yorker who was mesmerised by the shrine’s beauty Go East, Young Man Defanging the Snake

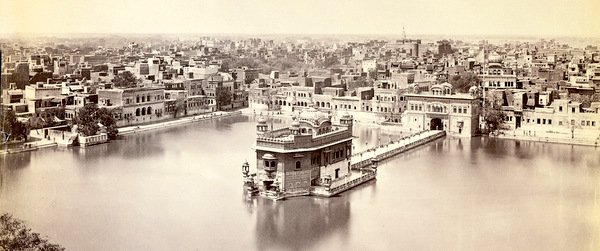

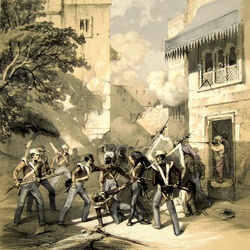

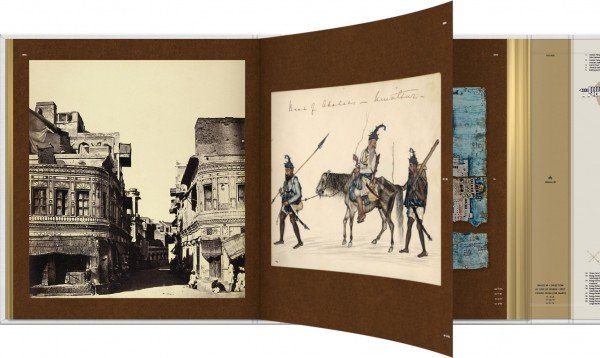

Rebel fighters across the land were forced into submission by a sizeable military presence that was maintained in Punjab in the aftermath of the war. To extinguish the remaining cinders of a once-blazing resistance, measures were also taken to disarm the entire populace. To encourage loyalty to Queen Victoria’s empire, the ranks of the army were thrown open to all classes of the Punjabi populace. In addition, collaborators continued to be nurtured at all levels of society, from village peasantry to landed gentry. All symbols of Sikh supremacy in Punjab were eradicated. The boy-king Duleep Singh (1838-1893) was separated from his mother, exiled and converted to Christianity, even though he played no active role in the recent wars. Likewise, political opponents were at risk of an early form of extraordinary rendition – their abduction and illegal transfer out of Punjab. The silver currency or Nanakshahi rupees of Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780-1839) and his successors, were called in, melted down and re-coined as the Company’s rupee. State property, including fabulously expensive jewels, weapons and textiles, was auctioned off by the British to contribute towards the expenses of the recent war. Amongst the Sikhs’ treasures was the fabled Koh-i-Nur diamond, which was swiftly whisked across the seas to be gifted to Queen Victoria as a token of Sikh submission. Thus, by the time Ireland reached the city of Amritsar in 1853, the subjugation of Punjab was deemed complete. After a stopover in London to see the opening of the Great Exhibition (at which was displayed the considerably reduced Koh-i-Nur diamond), the intrepid New Yorker finally arrived in India in early 1853. His itinerary first took him to southern and central India, where he spent ten months soaking up the sights offered up by serene temples, boisterous bazaars and gushing sacred rivers. But it was to the holy city of Amritsar in the north that his spirit of discovery led him in the winter of 1853. His initial impressions were favourable. ‘The streets’, he jotted in a letter to his mother, ‘are mostly paved with brick, and some are quite wide. The fronts of the houses display considerable taste.’ A street in Amritsar outside the Golden Temple of the Sikhs

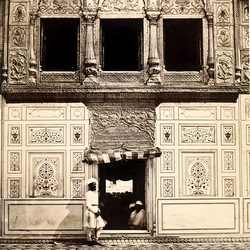

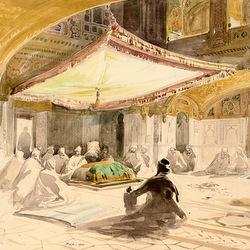

He soon reached the entrance ‘to the great tank, the Mecca of the Sikhs’, which lent its name to the city. At the threshold of the holy complex, at which stood the city’s police headquarters, Ireland was required to remove his shoes before being allowed to proceed. Aware of the reluctance of foreign visitors to India to walk barefoot anywhere other than the well-swept floors of their colonial bungalows, the temple authorities thoughtfully provided thick woollen socks for their comfort. Suitably attired, Ireland advanced in eager anticipation. As he emerged from the shadows he was confronted by a scene of considerable grandeur: ‘I entered the great quadrangle or court, of about four hundred feet square, with a terrace or walk of forty feet in width of tessellated marbles, surrounding the tank. The rear of fine and picturesque native houses, encloses and forms the exterior wall to the place; these, with overhanging verandahs, sculptured windows, and peculiar oriental look, and in some parts temple domes and spires, all lend an additional charm to this fairy scene.’ Agate, Cornelian and Jasper

Having traversed the bridge that connected the shrine to the perimeter, the curious New Yorker paused for a moment to examine the exterior décor. He was particularly struck by the brilliant contrast between the ‘exquisite gilding’ of the upper storey and the ‘purest white marble’ of the lower. Doubly-impressive was the beautiful marble-work ‘inlaid after the Florentine style of mosaic, with designs of vines and flowers in agate, cornelian, jasper, and other similar and beautiful stones.’ Stepping into the dimly lit sanctum sanctorum, Ireland came face to face with the Sikhs’ object of devotion, their sacred scripture, the Guru Granth Sahib. ‘The high-priest,’ he observed, ‘was performing some kind of service or devotion, with the Grunth (their Koran) before him on the cushion. At his side, and around the temple on a lower step or terrace, were worshippers sipping water and meditating.’

It was installed in the Golden Temple (then referred to as the Harimandir Sahib or ‘Exalted Temple of Hari’) where it ‘held court’ for the countless devotees from all walks of life who presented themselves as seekers of spiritual guidance, seeking to find meaning in their otherwise mundane and difficult lives. Relays of specially-trained devotional singers and musicians (including Muslim rababis) set its poetic verses to sacred song. For twenty hours each and every day, their melodious music reached into the farthest corners of the entire complex, aided by the four open doorways and enhanced by the resonating qualities of the vast pool of ambrosial water. Ireland soaked up this blissful atmosphere and came away overwhelmed, singing his own songs of praise for the Golden Temple in a letter to his mother: ‘Altogether this is the most exquisitely beautiful thing I have seen thus far in India. I have made a sketch, which, I am sorry to say, can give you but a very meagre idea of its beauties; nor can anything but the sight of the original itself, surrounded by all its oriental accessories.’ Even though Ireland’s world tour ended in 1857, his personal journal of letters and accompanying sketches were to live on in printed form. On the outbreak of the Sepoy Mutiny (or the First War of Indian Independence, depending on your politics) of 1857-58, a huge appetite was generated in the West for the very latest insights into British-Indian affairs. JB Ireland at the Golden Temple

In 1859, his observations, penned in his letters home to his mother and captured in his quaint sketches, were published under the title ‘Wall Street to Cashmere’. From that moment onwards, a steady flow of Americans, eager to immerse themselves in the exotic East for themselves, followed in Ireland’s footsteps. In the third and final part of this article, we’ll meet a Parisian-trained artist, a Methodist bishop, a pioneering travel journalist, a Yale University professor and a Hollywood heart-throb, all of whom fell in love with Amritsar and its ‘awesome’ temple of gold. To Be Continued… The full account of J. B. Ireland’s visit to Amritsar, along with an engraving of his sketch of the shrine, is reproduced in ‘The Golden Temple of Amritsar: Reflections of the Past (1808-1959)’. About the Author

Researcher, writer and publisher Parmjit Singh showing John McDonnell, MP for Hayes &Harlington, around the Golden Temple exhibition. Parmjit Singh is the co-editor of ‘The Golden Temple of Amritsar: Reflections of the Past (1808-1959)’. He is also the author of several other books on Sikh history including ‘Warrior Saints: Three Centuries of the Sikh Military Tradition’, “Sicques, Tigers, or Thieves: Eyewitness Accounts of the Sikhs (1606-1809)’ and ‘In The Master’s Presence: The Sikhs of Hazoor Sahib’. He is currently working on a special edition of ‘Warrior Saints’, due to be published in 2012. He is also a founding director of Kashi House, a not-for-profit social enterprise that produces illuminating resources on the culture and heritage of Punjab and the Sikhs. |

-----------------------------------------------------

Part One of this article is here:

http://www.sikhnet.com/news/america-s-love-affair-amritsar-part-1