December 15th, 2013: A Lone Texas Horse Woman Races Marwari Horse in a Boisterous Sikh Ride in the Punjab

December 15th, 2013: A Lone Texas Horse Woman Races Marwari Horse in a Boisterous Sikh Ride in the Punjab

From childhood, Houstonian Harsangat Raj Kaur took pleasure in mounting the back of a wild horse and riding off on it, guiding it with nothing but a rope around its neck.

Born in Texas, her mother remembers that by age three, spirited horses attracted Harsangat’s attention. Decades later, nothing has changed. Harsangat still gets satisfaction from running alongside an unruly horse that she later manages to conquer with her skill and a rope.

But in the years between childhood and adulthood, a transformation took place inside her.

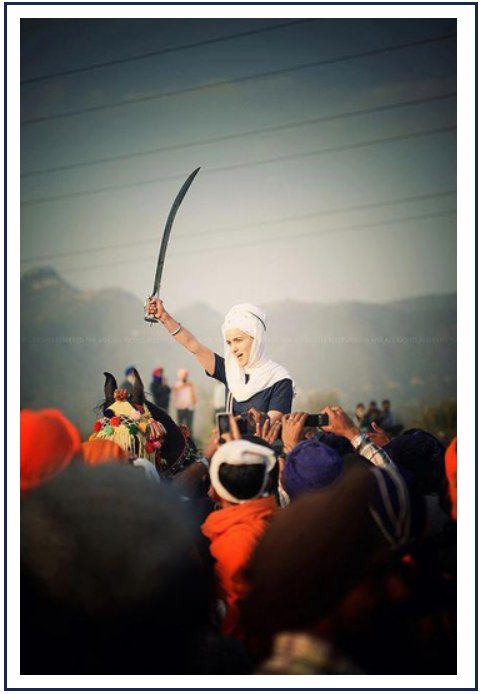

An outward manifestation of that change melds spirituality with the love of horses. In March, 2013, this expert horse woman and film actress traveled to Anandpur, India in the Punjab for the second time to participate in an ancient warrior festival. There, she rode in an intense race organized by fierce warriors in a festival that’s been likened to an Indian Olympiad.

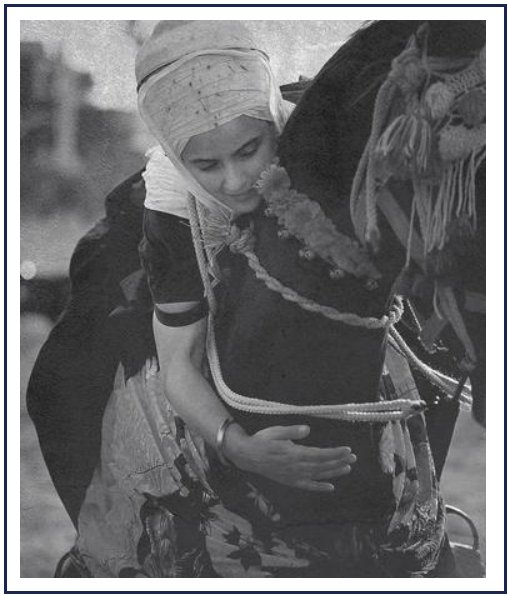

Mounted on a beautiful black stallion, she rode with Sikhs with a reputation as saint soldiers. Harsangat is the first woman to do so in some 300 years.

Mounted on a beautiful black stallion, she rode with Sikhs with a reputation as saint soldiers. Harsangat is the first woman to do so in some 300 years.

She joined this year’s race to call attention to the situation of women in India, many of whom experience great repression. Her desire is to also work closely with organizations in the U.S. and India with the goal of uplifting Indian women and promoting equal rights. “Women should be fearless and know that they are equal,” Harsangat explained. Her intentions align with modern Sikh warriors dedicated to protecting oppressed persons.

Harsangat’s horse? An unusual Marwari breed seldom seen outside India. These Sikh horses stand 15 to 16 hands tall, with ears that stand up straight and turn inward at the tips. Powerful, the breed emerged from mixing Arabian, native Indian and perhaps Mongolian horses. She obtained her borrowed horse less than 15 minutes before the free-for-all race began. She deftly guided the big animal, sometimes using signals from her feet, which were bare.

How did a Houston horse woman get to an Indian horse race that attracted thousands of onlookers? Harsangat Raj Kaur

To understand this, one needs to grasp how deeply Harsangat loves horses and a profound shift in her life.

When she’s in the Bayou City at rodeo time, Harsangat drives out to a local bayou and watches the trail riders and wagons making their way to the city’s Livestock Show and Rodeo. She aligns with the pleasure the travelers take from riding. As a child, she and her mother rescued horses and gave them better lives.

Now, she does ancient yogic exercises and meditations for at least half an hour every day, performs Sikh marshall arts, and recites Sikh prayers. In the Houston community, she teaches meditation and Kundalini Yoga. That wasn’t always the case.

Earlier in her life, Harsangat rode throughout the Southwest, mainly in rural settings. She liked to ride Arabians. By age 13 Harsangat served as a trail guide in Houston.

Earlier in her life, Harsangat rode throughout the Southwest, mainly in rural settings. She liked to ride Arabians. By age 13 Harsangat served as a trail guide in Houston.

She spent weeks and months studying the techniques of natural horsemanship from Native Americans in New Mexico, a la the movie Hidalgo. Elsewhere she learned western-style and hunter/jumper techniques.

To this day, Harsangat rides spirited horses on and near her mother’s land in the Houston area. This carries on traditions of her mother’s family, which is made up of ranchers from Montana.

Although she wanted to become a professional rider, an injury at a riding event in England stalled that plan. A sense of emptiness and depression followed.

Memories of her father helped her, as he has training in the recitation of ancient Sufi poetry. She remembered his poems, which soothed her. While later moving between Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, studies in art and jobs in fashion, theatre, and film developed. Just a few of the jobs: she worked for a magazine, helped on major movie productions, and served as a costume designer for films.

Surrounded by friends and opportunities for connection in each city, Harsangat still felt empty. Harsangat Raj Kaur

She turned to her beloved horses again, which hold a depth of meaning for her. While in Brooklyn, she began teaching children how to ride horses. At night she prayed, as her mother had taught her.

In California, she worked for a well known radio host and at Comedy Central. She jogged. While she did so, the emptiness persisted. But in Los Angeles, she began writing her own poetry. She slowly became a vegetarian. And, Harsangat found herself asking God to give her something to chant to help her keep going and take her mind off of everything else.

A friend invited her to a meditation group. She went. Western adherents to the ancient Indian Sikh faith populated the class. The Los Angeles teacher taught the first stanza of a famous Sikh prayer. Harsangat chanted the mool mantar along with them. (One God, the true name, the creator, without fear, without hatred, timeless, self-existent, made known by the Guru. Guru: GU = darkness to RU = light.) A flood of emotions washed over her for two and a half hours. Her depression lifted after having fought it for years.

Later she went to the United Kingdom and learned to recite more Sikh prayers, these meant for daily use. The Sikhs believed in the equality of men and women. Their tradition held that a series of Gurus were divinely inspired to organize the Sikh faith. Free of depression and very happy, Harsangat continued on.

She grew her hair long and got in touch with the fact that she believes horse riding can be healing. Harsangat went back to the West coast. In Los Angeles, she explored the therapeutic use of riding, a modality thought to help certain disabled persons, including some people with autism.

The Danish horsewoman, Liz Hartel, paralyzed from the knees down from polio, brought attention to its potential when she used the techniques to help her win the 1952 silver medal for dressage riding at the Olympic Games.

The Equine Assisted Growth and Learning Association (EAGALA) promotes such therapy. Because of its healing potential, Harsangat began gaining pleasure in working with a Los Angeles physician to “interpret” the horse as the doctor seeks to use horse riding to assist individual patients.

Harsangat’s spiritual awakening continued and she worked for a time in New Mexico, for the organization of Yogi Bhagan, who headed Kundalini Yoga training and the Sikh way of life in the U.S. until his death. She learned to do Kundalini Yoga and meditation from elders at Bhagan’s center. Devotees believe Kundalini fosters spiritual growth, health, and healing. Scientists showed that one of it simple exercises, Kirtan Kriya, turns over 60 human genes on or off.

Harsangat began teaching this yoga at a women’s shelter in Santa Fe, N.M.and she publicly committed to the Sikh faith.

In 2010 she first traveled to India, from whose complex culture Sikhism and Kundalini Yoga arose. Then, in 2012, she participated in the Sikh festival, Hola Mohalla, which dates to 1701.

Organized by the Sikh Guru Gobind Singh, this Indian festival honors the courage the Guru instilled in his ancient Sikh community. Members took up battles against tyranny. The Guru did not believe in India’s caste system and he sought equality for his countrymen. At the Guru’s festival all castes sat down together for meals of vegetarian food. To this day, those attending the week long festival camp out, sing sacred hymns, and listen to music and poetry together.

Organized by the Sikh Guru Gobind Singh, this Indian festival honors the courage the Guru instilled in his ancient Sikh community. Members took up battles against tyranny. The Guru did not believe in India’s caste system and he sought equality for his countrymen. At the Guru’s festival all castes sat down together for meals of vegetarian food. To this day, those attending the week long festival camp out, sing sacred hymns, and listen to music and poetry together.

At the modern event, modern Sikh warriors speed past participants riding on sweating horses urged on by riders carrying long spears and glistening swords. They wear turbans in the shape of cones and display carefully curled mustaches.

They also watch mock battles once staged by the Sikh warriors in a river bed near a Hindu temple. Guru Gobind Singh first used these as training exercises for his warriors, dividing them into two groups to fight each other. Now, festival goers can participate in a kind of series of Indian battle re-enactors exercises.

This event follows on Holi a spring festival of color that features pranksters throwing colored water, often with the outright intention of getting it on others. Indians let up on their social restraint during Holi.

For an American, the festivals expand cultural boundaries and open up possibilities. Harsangat dreams of a time when the Indian festivals impress others about the sanctity of life and value of women.

Her artwork reflects that wish. She creates sculptures and jewelry and works in mixed media. Certain seasons of the year, she designs dresses for Melissa Sweet.

And when Harsangat isn’t riding horses, she’s drawing them.

Contact her at www.theheartwarriors.com

Originally published by voices.yahoo.com