Ninder Johal is such a successful entrepreneur that he’s currently also president of the Black Country Chamber of Commerce – and much more besides.

Ian Halstead reports.

It’s often said that auditors chose their career after finding accountancy too exciting, which neatly indicates the public perception of both professions. However, it’s a safe bet that no-one’s ever met the gregarious and entrepreneurial Ninder Johal and realised he was once a dedicated student of accountancy and finance.

His passion is always allied to purpose though; and both are required in abundance given the array of positions on his portfolio. Johal is a board governor at Wolverhampton University, and vice-chairman of the board at Sandwell College, currently president of the Black Country Chamber, a board member of the Black Country LEP and a driving force of the National Asian Business Association.

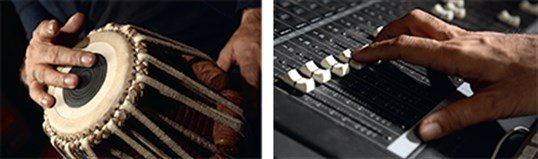

His grand passion is music though, especially bhangra, reflecting the Punjabi origins of his parents. It’s some 25 years since Johal founded Nachural Records, which took the dance music of Northern India into the mainstream charts with its crossover hit by Panjabi MC – ‘Mundian to Bach Ke’ (Beware of the Boys) – hitting number one in nine countries and making the UK top ten. “It was the first time a song in a foreign language, and played on foreign instruments, had achieved so much chart success, and it was a great feeling, especially as it took several years to break through,” admits Johal.

The song, which sampled the bass line of the theme tune to the 1980s TV show Knight Rider, was also later remixed by Jay-Z, and used on the soundtrack to the Sasha Baron Cohen movie, The Dictator, which meant another round of worldwide exposure for Nachural Records and its artists. “I still run Nachural, but my wife Narinda is heavily involved, and there’s a staff of six. My role nowadays is largely about getting the brand out there and doing the deals,” says Johal.

“Like most industries, music has been transformed by digital technology. In the old days, we needed several warehouses just to store all the CDs, but now music is much more accessible. Music is a small percentage of everything we do in terms of turnover now, but still very important because we love bhangra. My son’s studying management and economics at Aston University, and I’m hoping he can take the label on in a couple of years.”

Johal’s other business interests include an events and video production division – whose clients include the CBI, the NHS, HSBC and Mercedes-Benz – and Wednesbury-based HRA Loudspeakers, supplying sound systems for events and conferences. A new brand is about to blossom offering hi-fi speakers for the audiophiles, following the HRA model of designing and manufacturing all its products in the UK.

“Hi-fi still has a very ‘cottage industry’ feel, and even the established brands are only niche players, so I see a real opportunity here,” says Johal. “We’re working on the products, and will then test the market, before launching here and overseas. A lot of small business owners are reluctant to try export, but international trade doesn’t frighten me.

”However, I do understand people having a fear of the unknown, so it’s vital that the LEPs, the chambers and the other support services really engage with the business community to remove those fears.”

Remarkably, Johal, an accomplished tabla player, even finds time to tour with his band, Achanak, who have been playing concerts worldwide, and have issued twelve albums since forming in 1989. “The band was the catalyst for the move into events. As we toured, I acquired a lot of knowledge about lights, sound and production, and it seemed sensible to set up a specialist business. I had to change the way I worked though after setting up the new division. When we were playing and selling songs, our customers were mainly British Asians and foreigners. For production and events, I needed to meet different people.

“When I joined the Black Country Chamber, it was only to learn about networking. As I discovered more about the movement, and the challenges which small businesses faced, I became more active, and then joined the Black Country LEP to help guide other entrepreneurs and company owners.”

His schedule would be demanding for anyone, but it’s immediately clear that Johal’s contagious enthusiasm is underpinned by a solid streak of determination. “I was born in Sandwell in a traditional British-Asian family, so while my parents didn’t try to push me in any particular direction, they believed in the importance of a good education.

The first generation to come here typically had very tough jobs, often in foundries and the like, so they wanted to ensure that the next generation didn’t have to survive through hard labour, and I went to Leeds to study accountancy and finance”.

It seemed a logical route to secure, well-paid work in professional services, but after Johal’s graduation, his chosen career path became a cul-de-sac. “I wanted to work in accountancy, but after I’d had sixteen interviews and been rejected sixteen times, I realised that accountancy didn’t want me, and it was obviously time to consider other options. I felt that if my first degree hadn’t been enough to secure me a job that I needed to add to my qualifications, so I took out a loan from Midland Bank to fund an MBA at Aston University, specialising in marketing.”

Second time round was easier, as Johal was offered several jobs, before deciding to become a management trainee with industrial giants GEC. Based in Liverpool, he found himself touring the group’s sites across the country, and although the travel became too much after a couple of demanding years, the experience was an invaluable exposure to the world of marketing and sales.

He then joined another of the country’s best-known manufacturing brands, Lucas Industries, where the range of opportunities was much more to his liking. “Typically, it was going into a business, analysing its balance sheet, seeing how to resolve its cash-flow issues and then devising a turn-around plan,” recalls Johal. “Some of these companies were inside Lucas supply chains, some were inside Lucas itself.

“At the same time, I set up Achanak. Bhangra music was really taking off, and we had quite a big hit in the Asian market, ‘Lak Noo Halade’. That meant we were in demand for gigs, so for a period I found myself working until the early hours, snatching some sleep and then heading off to Lucas.

“Eventually, I acquired the experience and the confidence to decide I could make a living from music, so I set up Nachural Records, signed several bhangra artists and decided to leave Lucas.”

However, persuading the wider music industry, record shops and non-Asian customers to share his love of the quirky Punjabi dance music wasn’t easy. “I was convinced it could cross-over, but no-one believed me. Eventually, I spent ten years promoting bhangra before the breakthrough. I went to Cannes and Nice, to the film festivals, trying to persuade people to listen to the music, and over the years, it cost me a fortune.

However, persuading the wider music industry, record shops and non-Asian customers to share his love of the quirky Punjabi dance music wasn’t easy. “I was convinced it could cross-over, but no-one believed me. Eventually, I spent ten years promoting bhangra before the breakthrough. I went to Cannes and Nice, to the film festivals, trying to persuade people to listen to the music, and over the years, it cost me a fortune.

“I used to walk into record shops in the UK, time after time, and I knew what the staff were thinking: ‘Here comes that man again trying to sell us music that nobody wants to buy.”

Johal’s dream finally became reality, but by a very unlikely route: “We’d released Panjabi MC’s songs, including ‘Mundian to Bach Ke’, in 1998, but they did nothing outside our core markets. A good three years later, an Italian label asked if they could use it on a dance compilation, and then a Turkish label asked to use the song, so we re-released it at the end of 2002.

“Two months later, it suddenly took off in the dance charts, and in the summer of 2003, someone rang from Germany to ask if they could use the song for worldwide distribution.”

The call came from Warner Bros, and was followed by Sony and Universal. Copyright lawyers were also soon in touch, proposing action against record pirates pushing out counterfeit versions in the US. Johal declined, judging that their efforts would simply promote the song to even wider audiences. It proved an astute decision as the Nachural Records track became the best-selling global dance song of 2003. Jay-Z then rang to ask if he could add his voice to the song, which sent bhangra into the billboard charts for the first time.

Johal’s devotion to the cause certainly taught him the merit of perseverance, while also highlighting the narrow margins which separate success from failure. As an entrepreneur and committed believer in the Black County, it’s intriguing to get his take on the devolution agenda, the metro mayor concept and the immediate future for the region’s economy.

“The decision to abolish the Manufacturing Advisory Service (MAS) really was a bolt from the blue, and quite brutal too, how it was announced in an email,” says Johal. “If the Chancellor genuinely intends to ‘rebalance’ the economy, as he says, it made no sense to abolish this service.

“Everything I’ve heard about the regional MAS advisers was good, they were clearly appreciated by the companies they helped, and such a service will be missed. The amount they were spending wasn’t that great, so it won’t make much difference to Whitehall’s budgets.

“I did expect more protests from local MPs, but Labour does seem to be more focused on internal issues at the moment, rather than taking the government to task.

“The wider regional picture still looks strong. We hear regular good news from JLR, UK car sales have just hit a record high, aerospace is buoyant and the levels of foreign direct investment coming into Greater Birmingham is very impressive.

“I appreciate that China’s GDP growth isn’t as high as it was, and the collapse in oil prices has been dramatic, but we do seem to have an unfortunate fascination with bad news. Devolution has to be good news, as long as we get sufficient finance to make a difference, and as long as the metro mayor isn’t a career politician, I’ll be happy.”

As will Panjabi MC, whose new CD is out shortly on Nachural Records. And Jay-Z? Johal still has him on speed-dial, just in case.