|

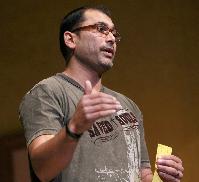

| Michael Sears Arno Michaelis (left) of Milwaukee, a former white supremacist now working to share how destructive his beliefs were to him and others, teams up with Pardeep Kaleka of Greendale, a Sikh whose father was killed in the Oak Creek temple shooting, to give an anti-bullying seminar Monday at Cudahy High School. |

Cudahy - Arno Michaelis, the former white supremacist, went first. He stood across the stage at Cudahy High School's auditorium from his recent partner and friend Pardeep Kaleka, the two men united by the bloodshed four months ago.

"On Aug. 5," Arno began, "a man who I used to be walked into the Sikh Temple and murdered six people because they had brown skin, because they had turbans on their heads."

One of the six who died that day was Pardeep's father, Satwant Kaleka, president of the temple, a man who would not have condoned his son's urge to stay angry after the shooting.

"It would have made my father's legacy, everything he worked for his entire life, a sham," Pardeep said.

|

For 90 minutes Monday, the crowd of 750 students sat riveted. They watched the two men offer a vision of what comes after an act of hatred.

The story had its beginnings after 40-year-old Wade Michael Page went on his rampage and then took his own life.

That night and afterward, Arno felt a weight of responsibility. No, he had not pulled the trigger, but as he told the students, "in many ways I helped create the environment for this."

That night and afterward, Pardeep felt grief and the frustration of not understanding what kind of person did this to his father and the others. There was no one to ask. Page was dead.

Pardeep heard about Arno, a Milwaukee man who founded one of the largest white power groups in the country, then left the movement to work for the group Life After Hate. This was a man who might know what was inside Page's brain.

Pardeep, 36, emailed Arno, who is 41. He asked to meet him.

On Oct. 22, the two met at a Laotian restaurant in Milwaukee. Arno picked the place. He arrived first, feeling nervous. There was still the voice that told him you bear some responsibility. The swastikas tattooed on his arm had been covered up by other ink, but they could not be erased. Arno worried he would break down weeping.

Pardeep had butterflies in his stomach. He wore a bandage over his left eye and Arno's gaze went straight to it. He thought Pardeep looked like a fighter.

What happened? he asked.

Pardeep explained that he'd been giving his daughter a bath when the hook on the luffa caught in his eyelid and tore it. Arno, accident prone himself, decided right away: This guy's awesome.

Their 90-minute dinner expanded into two hours that turned into three hours that turned into four. Arno, a recovering alcoholic, ordered a pot of tea and they passed it back and forth, filling each other's cups as the night wore on. It was a back-and-forth ritual like their conversation.

How did you get into it? Pardeep asked of the white power movement.

Arno had not been poor or hated at home, though his parents had struggled with alcohol.

Honestly, Arno said, it was something I was good at and I hadn't been good at anything before. I was good at fighting. I was good at hating.

He explained how he joined the movement and stomped across stages as lead singer of the white power rock band Centurion. He explained how he beat up on other races, but finally found it impossible to reconcile the hatred he felt for them with the acts of kindness he often received from them.

Once, a black woman at McDonald's saw the latest swastika tattoo on his finger, and told him: You're a better person than that.

Pardeep shared his story of being a first-generation immigrant from India. He talked about his father, a man who worked hard, was a regular Mr. Fix-It who brought the lawn mower onto the living room rug to repair. They had something in common. Arno's dad was a Mr. Fix-It, too.

Pardeep yearned to know what was going on inside the head of the man who killed his father. Arno took him there as best he could. From his own experience, Arno said Page was consumed with hate and fear. Everyone who was not a white racist was part of a vast conspiracy. They were enemies out to destroy him. It was a terrible way to live, Arno explained.

The two men left the restaurant late that night. Pardeep felt rejuvenated. He didn't hate Page. He felt sad for him.

Arno felt grateful. He looked at Pardeep and saw "how chill and together he was" even sitting across from a former white supremacist, a man steeped in the same hatred that caused his father's death. He thought how beautiful it was that Pardeep was continuing to practice the values of his father.

The high school auditorium was quiet for a long time as the men shared their stories. Then the students got to ask questions.

Someone asked Pardeep how he felt before he met Arno, and he talked about the butterflies and the fact that some of his relatives felt, "Once a skinhead, always a skinhead."

But he said, "Arno represents for me what is great about this country." He changed his ways and dedicated himself to opposing the hatred he once embraced.

Then, in front of hundreds of students, Pardeep called the man across the stage "a hero."

Arno's eyes glistened.

"I'm very humbled by that," he said.

The two men finished their presentation. The students broke into applause and then rose, still clapping. Afterward the speakers stood together by the front of the stage as young men and women approached to shake their hands.

One was Jazmin Jones, 19, a senior who plans to join the Army Reserves. She is black. She asked Arno what it was like to stand beside her.

"To be honest," Arno said, "I feel grateful when I'm talking to people I formerly would have hated. I feel very grateful."