Some days my roving eye wanders over to the obituary column in the newspaper; I suppose I am relieved not to find my name in the list. Sometimes I find someone whose life was dedicated to a cause that is bigger than the self, one that any person would love to make his own.

I salute one such man today.

In 2013, Saul Kagan died at 91 and the New York Times carried over half a page of obituary with photographs.

Naturally I wondered what he had done to deserve so much attention.

Let me point to some highlights of his life:

A Jewish refugee from the Second World War who lost part of his family to the Nazis, Saul Kagan was the Founding Director of an organization dedicated to secure restitution for Holocaust survivors and their heirs. It took nearly half a century to negotiate the tricky legal landscape but he led the process of securing legal and financial redress from the successor states of the Third Reich and its allies.

Because of his efforts, about 600,000 survivors received payments. The restitutions totaled more than $70 billion.

Saul Kagan wrangled and negotiated successfully with nations like West Germany and Austria but also with corporations like Krupp, Siemens, Volkswagen and Daimler-Benz, among others, as well as banks like UBS, and Credit Suisse.

It was not his personal cause, but Saul Kagan spent his life in a cause bigger than the self. This is the very definition of altruism. At the end he described his achievement as only “a small measure of justice.” He said, “A thousand years of history destroyed in 12 years were beyond compensation.” Former U.S. President Bill Clinton said: “It is no exaggeration to say that for 50 years Saul Kagan was the heart, mind and soul of the search for justice for survivors of the Holocaust.’

How did he get to the position where he could become so effective a hunter of those who looted his people so fully and freely? How did the many doors open that led him to the guilty ones?

Saul Kagan was fluent in German, Polish, French and English; fought in the War alongside the allies against the Nazis, and after the armistice was appointed Chief of Financial Intelligence by the United States postwar military government in Berlin. There he learned how Jewish property, personnel and institutions had been systemically looted by the Nazis, their collaborators and friends.

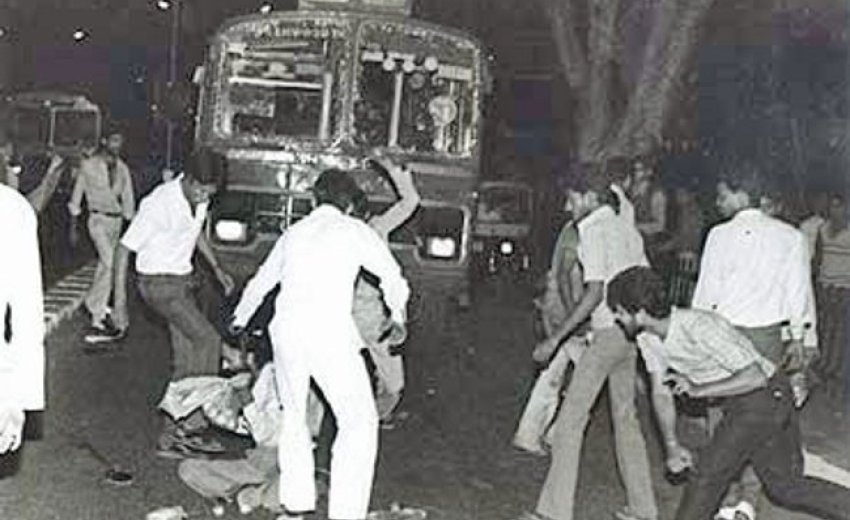

My thoughts flew to more recent times in a country and culture much more distant: The 1984 government-aided, attempted genocide of the Sikhs in India.

In summary, the events lasted just over a decade. Sikhs were arrested and held without trial or killed in fake encounters by the army and the police. Hordes of armed hoodlums appeared in Sikh neighborhoods to kill, burn, rape and loot unarmed Sikhs. Sikh properties and businesses were targeted and razed. This was in India where arms remain strictly licensed and controlled, kerosene for burning people and property was rigidly rationed and not available in the open market, and in those pre-Google days one could not download addresses and ownership information of property. Trucks were hard to get but the killers had them. They also had lists of Sikh-owned properties and guns a-plenty. The mayhem continued for days while the police stood by or egged on the looters. Thousands were killed but till today, 33 years and 11 governmental inquiry commissions later, less than a handful have been identified or convicted of any crimes.

I offer an essential caveat: Saul Kagan’s base was the United States; a country that had led and won the war against the Nazis. Kagan was operating from a safe haven. There is no way that anyone could have similar expectations from a Sikh in India at this time because in this matter India is the rogue state. The two situations — the world after the Second World War and India 33 years after 1984 — are not comparable, yet they hold some lessons for us all.

I understand fully that, during that decade, many Sikhs collaborated with the government and their lips remain sealed even today. Today many Sikhs hold influential positions within the Indian governmental bureaucracy, some at fairly high levels. They know what happened; they know who is or isn’t guilty; they know where the evidence is buried, and how it can be unearthed.

But we also know the imperatives of survival and self-preservation that are not open to easy analysis.

Saul Kagan was lucky to be living and working in the United States. In India, anyone who asked too many questions would likely disappear like the legendary Jaswant Singh Khalra, who discovered the graves of many innocent Sikhs killed by the police who remain unaccountable. I also remind you that people like H.S. Phoolka, a lawyer in India, are no less than the Saul Kagans of the world but the circumstances are different.

But one needs to think of the times beyond today and beyond the here and now. We must think of the ages to come. Only then are time and distance conquered. One must transcend the self somehow, sometime, somewhere.

That’s why I have absolutely no problem with a small diaspora based Sikh organization like Sikhs for Justice taking on the might of the Indian government and suing the Indian political leadership in the judicial system of the United States for human rights violations. I have absolutely no problem when they offer rewards for serving legal papers on Indian politicians and leaders whenever they visit the United States on their periodic jaunts. The central idea is always the question of identifying those who remain responsible for the killings of thousands of Sikhs and the lack of transparency and accountability that defines India. The idea is to never let the story die.

It smacks of a David v Goliath situation but so be it — a parable carries many a moral lesson for many a millennium, and we know that the Biblical tale ended just fine from David’s point of view.

We do need a Saul Singh Kagan somewhere soon.

Guru Granth pointedly tells us (p 474): “Aap gavaaye seva karay taaN kitchh paaye maan” that to find oneself, first get out of the preoccupation with the self and subjugate the self to a cause bigger than the self.