In the souvenir booklet printed to commemorate the 494th birthday anniversary of the founder of the Sikh faith, Guru Nanak, and the opening of the Guru Singh Sabha Gurdwara in Nairobi, Kenya, on November 1, 1963, a chapter is dedicated to the arrival of the first Sikhs in what is Kenya today.

It reads: "Men were packed in the ship like sardines in a tin... They were crossing a vast ocean... Amidst this group of men was a small party of Sikhs who had come on board, led by one who reverently carried on his head a small cot on which sat what looked like a big book, richly draped. Another man ceremoniously waved over it a large and ornate fan.

"The Sikhs were carrying their Holy Book - the ever-present embodiment of their faith - with them. On the overcrowded decks travellers willingly created an honourable place for it. While there was shouting and pushing all over the ship, there was a quiet deep air of veneration around this Holy Book - the Guru Granth Sahib."

I continue reading the souvenir booklet.

"These particular Sikhs were part of the first indentured labour force that was brought over from India in 1892 to build the Uganda Railway. They were all men of skill - carpenters, blacksmiths and masons. Within a few weeks of landing at Mombasa, they erected a small wood and iron Gurdwara at Kilindini on land and with materials provided by the Railway authorities. This was the first Sikh Gurdwara on the African continent."

In this first Sikh gurdwara at Kilindini, the Sikhs must have placed the first Guru Granth brought to Africa. From there it is said to have been taken to the Makindu Gurdwara, from where it was taken to Nairobi in 1972 and eventually found its way to Kericho.

Fast forward to 2010. The date, February 4.

A train, the Guru Express, arrives at Makindu station ornately draped with the Sikh colours of blue and yellow and the Sikh emblem, the Khanda, painted on the carriages.

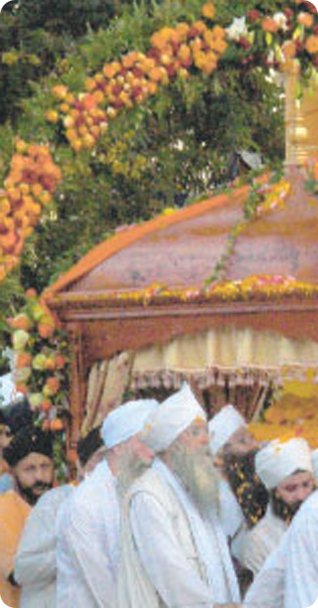

Inside, the final prayers are recited from the Guru Granth before it is closed and brought outside to the crowd waiting at the station - which, apart from Sikhs, includes many Africans too.

I am excited like everyone else, for the Guru Granth being returned to Makindu Gurdwara from Kericho via Kisumu on board the Guru Express, is believed to be the original one from 1892.

There is an air of deep reverence as the holy book is carried outside... much, I imagine, like the scene back in 1892.

It is placed on a specially prepared palanquin and carried on the shoulders of the faithful to a newly constructed gurdwara within the grounds of the Makindu Sikh Gurdwara, one of the most revered Sikh shrines in the world outside Punjab and India.

The five-day journey of the Holy Scripture - from Kericho to Kisumu by road, and from Kisumu by special train stopping at Nakuru and Nairobi for prayers for Kenya's peace, prosperity and unity - has been dubbed the "Sacred Travel for Peace, Prosperity and Unity."

The new gurdwara is built with materials retrieved from an earlier gurdwara constructed in 1926. The front two windows are from that time. "Labour, not trade, is the foundation of the Asian African heritage in East Africa," reads the brochure for the Asian African exhibition at the Nairobi National Museum at the turn of the last century. The work of the railway labourers is the bedrock on which later endeavours came to be based.

The 1963 souvenir edition reads, "As the railway pierced its way into the interior, the Sikhs built a temporary Gurdwara at every major camp and one of these, at Makindu, is now a permanent gurdwara right on the Mombasa road."

It is a nostalgic journey in the train for many of us, descendants of the original labourers who came more than a century ago, armed with only their simple belongings and the Guru Granth.

"Today, l am talking to 3rd and 4th generation Kenyans who are the great grandchildren of the builders. You have to be proud of your forefathers," said Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga, who came to pay homage to the Guru Granth being recited in the Guru Express.

"You may be Kenyans of Indian origin or Kenyans of Sudanese origins, but we are all Kenyans.

"We need more peacemakers of this kind," said the Prime Minister referring to the political upheavals from 1990 to the infamous post-election violence of 2007, which reached breaking point in 2008. "Kenyans have a shared responsibility and we have to reconcile and unite."

I'm looking at a sketch of Makindu Station in a series drawn by the late Mohamed Sadiq Cockar, a Sufi and a surveyor in the Public Works Department ("PWD") of the Kenya Colony in 1926.

A trained draughtsman and architect, each page is a narrative of the railway stations that hosted them.

In his Makindu sketch, he shows the Makindu Gurdwara and writes, "Big space with many rooms, the Sikh Temple for free food and accommodation."

It shows a busy railway station complete with the Nairobi-Mombasa road, two baobab trees between the mosque and the gurdwara, and the PWD staff encamped on the periphery of the town with giraffes and other game in the vicinity.

With a busy station to look after, the Sikh community increased in Makindu, the men working in the railway workshop and the trains.

On April 27, 1930, a new Gurdwara was opened at Makindu in the presence of about 150 Sikhs from East Africa.

The new gurdwara is described as "a magnificent stone building with fine arches at the front and back and a beautiful garden." The building cost the princely sum of Ksh.15,000 - just about $200 at today's exchange rates.

Unfortunately, the railway that "opened up" the so-called Dark Continent - few outsiders had ever ventured beyond the Coast till then - took a turn for the worse after the 1980s.

Becoming the East African Railways after the Independence of the three countries in the 1960s - Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania - internal wrangling saw the amalgamation break.

Today, the Rift Valley Railways, having taken over the dysfunctional Kenya Railways Authority, has turned out to be a controversial investment, with thousands of railway workers laid off and passenger services becoming infrequent, a pale shadow of its former heyday when the prestigious passenger service, say travellers, enjoying fine dining in the restaurant cabins served on fine porcelain and silver cutlery.

However, the Prime Minister reminded the gathering of plans now afoot to modernize the rail system and expand the network to Kampala in Uganda and run another line to Juba in Southern Sudan from Lamu, where the second seaport is being built.

"Ik Oankaar," recites Bhai Mohinder Singh from the opening words of the Guru Granth. He is the eminent Sikh scholar and leader of the Nishkam Sewak Jatha, a religious charity headquartered in the United Kingdom, that has organised the return of the old manuscript of Guru Granth Sahib to Makindu.

It means: God is One, the Creator and Lord of all creation. Everything is because of Him. The message is complete in this verse. All other verses elaborate on this."

Bhai Sahib continues: "According to the Sikh faith, we have a responsibility towards the entire creation. The Japji Sahib, which is the morning p rayer, is about the environment. It mentions the elements - air, water and Mother Earth - which we must not pollute because we are interdependent. It means that we must tread carefully on Mother Earth. Without religion," he continues after a pause, "there is no environment."

rayer, is about the environment. It mentions the elements - air, water and Mother Earth - which we must not pollute because we are interdependent. It means that we must tread carefully on Mother Earth. Without religion," he continues after a pause, "there is no environment."

Born in Uganda in 1939, Bhai Mohinder Singh, was raised and schooled in Kenya. His father worked with the railways and the family moved from station to station, frequenting Makindu. Trained as a structural engineer, he emigrated to England in the 1960s.

Deeply devoted to the teachings in the Guru Granth, he is the leader of the Nishkam, an organisation devoted to Sikhism.

Between 1995 and 1999, the organisation, under his leadership, redid the external gold gilding of the Golden Temple or Harmandar Sahib in Amritsar. "It was a complex procedure. The first gold gilding of Harmandar Sahib was done by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who consolidated the Sikh empire. It took him 27 years, from 1803 to 1820, to complete the job, finding time between the many battles he fought to consolidate the Sikh empire. We did it in four years."

He explains the process. "We put 24 layers of gold leaf on copper plates that are 99.9 per cent copper. It's almost pure. The gold leaf is pasted on the copper plates with mercury. The gold leaf is made from gold bars cut into pieces of one square centimetre and manually pounded 120 times per minute till the thickness is 0.76 microns or one thousandth of a millimetre." I gasp at the sheer thinness of the leaf. The original leaf coating had 12 layers and lasted almost 177 years.

Bhai Sahib's intention in having 24 layers of gold leaf, is that it will last twice as long - almost four centuries.

"This technology in Punjab goes back to about 600 years and the art is passed from generation to generation and jealously guarded. But l was determined to redo the Golden Temple because it had started to corrode because of the copper within. But some things had to be determined, like the thickness of the gold leaf, which until then nobody knew.

"With my engineering background and being in Birmingham where the Industrial Revolution started, l managed to take an original gold plate to a research institute there. The officer had never seen a hand-beaten gold leaf."

The historical manuscript of The Guru Granth returned to Makindu is in the care of Bhai Mohinder Singh. Babaji is nostalgic about his Kenyan roots. Before inheriting the leadership from Bhai Puran Singh from Kericho, the founder of Nishkam, he was told of the leader's desire to see the old Guru Granth returned to Makindu Gurdwara.

"The Guru Granth Sahib was taken from Makindu Gurdwara in 1972," explains Joginder Kaur who was married in Makindu in 1967 to a railway worker. She still resides in Makindu, the only permanent Sikh resident in town. "There was an accidental fire. A cat knocked down the diva (candle holder) and everything burnt to cinders except the Guru Granth Sahib. It was intact," she recalls.

The Holy Book was brought to Guru Singh Sabha Gurdwara in Nairobi for safekeeping and at some point taken to the Kericho Gurdwara, where the organisation has built a new temple including a technical college for the youth, who are admitted regardless of creed or caste.

I am still curious to know if the Guru Granth Sahib returned to Makindu Sikh Temple is the 1892 version. "This is the only hand-illuminated copy of the Granth Sahib that l have ever seen," says Bhai Sahib as he is fondly called.

"This particular copy may be one of its kind in the world today," says the white-bearded Bhai Sahib, simply clad in a white cotton kurta and pyjamas with the traditional "kilemba" (turban) of the "kalasinghas," as Kenyans call them.

[Courtesy: The East African]