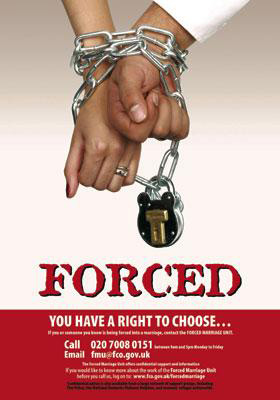

Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that "marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses". If not, then the marriage is deemed a forced marriage. Here in Britain, the government's Forced Marriage Unit (FMU) deals with around 400 cases a year – although there are thought to be far more unreported cases. New evidence assembled by Disability Now suggests that a significant number of those marriages involve disabled people.

Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that "marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses". If not, then the marriage is deemed a forced marriage. Here in Britain, the government's Forced Marriage Unit (FMU) deals with around 400 cases a year – although there are thought to be far more unreported cases. New evidence assembled by Disability Now suggests that a significant number of those marriages involve disabled people.

Victims of forced marriage are coerced into being wed. Many are subjected to domestic violence by family members to force them to marry. Some are kidnapped if they resist. Then many are either sexually assaulted or serially raped (if they cannot or do not give consent to intercourse) once married. A number of forced marriages have ended in murder. Most cases involve people from the Asian sub-continent but others have involved Eastern European, Middle Eastern and African victims. Most of the victims are young; and a growing number are thought to be disabled. A spokeswoman for the FMU acknowledges that it has "handled many cases involving men and women with mental health needs or learning disabilities" although it does not routinely gather information on whether victims have an impairment.

One recent case, which went to the Court of Appeal, involved a young British Asian man with autism and learning difficulties (known as IC), who was married by phone to a young woman who was to be brought to England from Bangladesh. The judges dismissed the appeal of the young man's father who had argued that he was the legal guardian and could consent to the marriage on his son's behalf. Lord Justice Thorpe said that introducing IC to a wife whom he had never met would be "likely to destroy his equilibrium or destabilise his emotional state". The judge continued that if the wife consummated the marriage, she would be "guilty of the crime of rape" and that the marriage was "potentially if not actually abusive". The family are now considering appealing to the House of Lords.

In another case, Yvonne Rhoden, a detective constable in the Violent Crime Directorate of the Metropolitan Police, says that young, deaf, Asian twin women presented themselves at a police station, fearing that they were about to be wed against their will. The police were able to intervene – but Ms Rhoden points out that the women were lucky to find a station with a signer. Not all have been so lucky. Saghir Alam (pictured), who sits on the disability committee at the Equality and Human Rights Commission, is concerned about the rising number of such cases. He supports the right of disabled people to marry: "Ten or 15 years ago young disabled people in our community couldn't get married, and we certainly don't want to prevent marriage. But there must be free consent under sharia law. We don't want people being coerced into marriage."

Saghir Alam (pictured), who sits on the disability committee at the Equality and Human Rights Commission, is concerned about the rising number of such cases. He supports the right of disabled people to marry: "Ten or 15 years ago young disabled people in our community couldn't get married, and we certainly don't want to prevent marriage. But there must be free consent under sharia law. We don't want people being coerced into marriage."

He has identified a number of reasons why parents seem to be turning, increasingly, towards marriage for their disabled offspring. As parents age, he says, they fear leaving their disabled children behind to fend for themselves – many feel isolated and know little about the model of independent living championed by the wider disability movement. He says:"It is a caring decision, but by the wrong means…they are trying to get the best for their children, but when I look at the decisions they have made I am quite shocked."

A veteran of the struggle to prevent disabled people from forced marriages is social worker Mandeep Sanghera, who has campaigned against the practice for 15 years. She does not mince her words: "Asian people with learning difficulties are being abused by family, friends and the community." The phenomenon is increasing, she says, because of a number of key factors.

Tightening eligibility for social care means that many disabled young people lose crucial support during the transition between children's and adult services. Social services, she says, "tend to turn a blind eye" because it relieves pressure on their stretched budgets. And this all happens as the young people reach marriageable age – with disastrous results for all concerned. Despite the good intentions of the parents, the disabled people are not given the right to live independently and the young women who care for them often develop mental health problems themselves, Ms Sanghera says.

A number of members of parliament have raised this issue over the last few years, as have the charities Voice UK, the Ann Craft Trust and Respond, which consider it a "serious, but largely hidden problem".

Robin van den Hende, who speaks for the three charities, emphasises that people with learning difficulties, who have capacity, have, for far too long, been "denied their rights to marriage and a family life" but that evidence shows that a significant number are being forced into wedlock. He continues: "People with learning difficulties are likely to find the experience of forced marriage confusing and traumatic, particularly if crimes have been committed in association with the forced marriage." Voice UK suggests that Independent Mental Capacity Advocates (IMCAs) could be used more frequently when it is suspected that a disabled person is being married under duress. Thus far, though, he says, disabled people with families are not often given access to an IMCA – even when their relatives may be abusing them.

Voice UK identifies another trend, in which people with learning difficulties are "forced into marriage as a means of assisting a claim for residency or citizenship and the people with learning disabilities may then be divorced after such a claim is successful."

The director of UK Visas, Mark Sedwill, confirmed this trend, when he gave evidence to the home affairs select committee in March this year. He said that 452 visas for Pakistani applicants were refused last year on the ground of family abuse, and most were because of fears of forced marriage; 86 of those cases involved vulnerable adults, including people ho were "severely disabled". Teertha Gupta, for his part, believes that many Asian families see marriage as a way of controlling "troublesome teenagers", whether they be disabled, gay or associating with the wrong person.

Dominic Grieve MP, the shadow attorney general, raised another disturbing issue, saying that "there is a school in my constituency for children with learning disabilities. I am afraid that there is a consistent pattern of girls being removed at the age of 16 to be sent to the Indian sub-continent…to be married."

Saghir Alam says that the government rhetoric on forced marriage has felt like a "cultural attack, not a human rights issue" for many Asian people – and the barriers have gone up as a result: "People need to work with the parents, to find out why disabled people are being pushed into marriage. I think it is because there is no independent living provision for many of them and these parents are suffering in isolation."

Liz Sayce, chief executive of RADAR, says: "As long as some BME and faith communities have shockingly low access to information, advocacy, independent living support and rights, it will be difficult to create a momentum that takes us beyond marriage as the way to assure some form of future for a disabled child. Forced marriage is wrong - but the way forward is strong engagement with community leaders and disabled people from those communities."

Teertha Gupta, a well-known barrister specialising in international family law issues, wants learning disability teams, schools and support workers to be far more aware of the dangerous age – around 16 – when disabled young people are likely to be coerced into marriage. Ms Sanghera wants to see far better reporting of forced marriages. She, too, is damning about government action: "I don't think that the government wants to know how big a problem this is, or could become."

A spokeswoman for the Home Office says that "the Forced Marriage Unit has developed practice guidelines for social workers working with young people and vulnerable adults facing forced marriage".

One of the stipulations of the Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act is that these guidelines will be reissued on a "statutory footing". The act is due to be implemented this autumn. Whether such guidelines are enough to protect young disabled people from forced marriages, however, remains to be seen.

• If you are affected by the issues in this article, please ring the Forced Marriage Unit on: 020 7008 0151 or email them at [email protected]

CASE STUDIES

-

Rani is a young woman with mental health needs and learning difficulties.

She lives at home with her mother. Over a year ago Rani's mother came under pressure to arrange a marriage to a young man who had come over from India. He wanted to marry a British citizen so he could live in Britain.

Rani's mother persuaded her to marry the young man. As soon as they were married, her husband started to steal her benefit money and post it back home. He also assaulted her on a regular basis and she asked her mother to help her. Rani's family told her to put up with the abuse. Rani then had a miscarriage. Her husband became more aggressive. Then her husband obtained a visa to stay in Britain and wanted to divorce her. Rani has now moved back in with her mother. (Details provided by Mandeep Sanghera.)

-

A local authority sought leave to prevent a 17-year old deaf woman with learning difficulties from being sent to Pakistan to marry. The young woman communicates through British Sign Language, which her parents do not understand. The court emphasised that the young woman had a clear capacity to marry but did not want to move to Pakistan to be married and then to live. The court made an order requiring that the daughter be properly informed, in a manner that she could understand, about any future marriage plans.