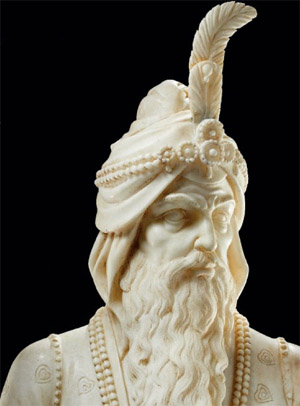

A previously unknown marble bust of the Maharaja Ranjit Singh will soon be on the auctioneers block in London. This stunning piece crafted in Europe in the 19th century is expected to reach $100-140,000 and is redolent of the Duleep Singh sculpture by Royal Academician John Gibson (1790-1866) that fetched a staggering £1.7m in 2007.

A previously unknown marble bust of the Maharaja Ranjit Singh will soon be on the auctioneers block in London. This stunning piece crafted in Europe in the 19th century is expected to reach $100-140,000 and is redolent of the Duleep Singh sculpture by Royal Academician John Gibson (1790-1866) that fetched a staggering £1.7m in 2007.

With the exception of the Sikh Gurus, Ranjit Singh is probably the best-known figure in Sikh history. The writer Chirsty Campbell describes him as “One of the greatest rulers of Northern India [who] built an empire which stretched almost from the Indian Ocean to the Himalayas.”

Short lived, his rule lasted a mere forty years and could hardly survive a further generation, but in the opulent court of the Lion of the Punjab the arts and the sciences prospered.

The Punjab was the flat plain into which invaders, rulers and plunderers swept from the Persia and Afghanistan in search for the riches of the royal courts in Agra and Delhi. Greeks, Christian and Muslim invaders clashed physically and culturally with the predominantly Hindu Punjab over hundreds of years to shape a cultural milieu which was defined by that conflict. Into this mix was born the Sikh faith in the sixteenth century and from that the inimitable Sikh warrior class, the Khalsa, in the final year of the seventeenth century.

By the time that Ahmed Shah Abdali had made his final two invasions into India (specifically to hit the Sikhs who had been plundering his caravans) the Sikhs as a guerrilla force were in their zenith. They were organised into 12 confederacies who held informal power in a variety of fiefdoms and who periodically warred amongst each other – especially when there was no external threats. The 12 confederacies hailed a single master in the Buddha Dal – an itinerant religious body. Even in this seemingly organised confederacy there was chaos and weary travellers and spies noted the uneasy structure which made up the origins of the early Sikh courts.

“As for the Seikhs, that formidable aristocratic republick, I may safely say, it is only so to a weak defenceless state, such as this is. It is properly the snake with many heads. Each zamindar who from the Attock to Hansey Issar, and to the gates of Delhi lets his beard grow, cries wah gorow, eats pork, wears an iron bracelet, drinks bang, abominates the smoking of tobacco and can command from ten followers on horseback to upwards, sets up immediately for a Seik Sirdar, and as far as is in his power aggrandizes himself at the expense of his weaker neighbours; if Hindu or Mussulman so much the better; if not, even amongst his own fraternity will he seek to extend his influence and power; only with this difference, in their intestine divisions, from what is seen everywhere else, that the husbandman and the labourer, in their own districts, are perfectly safe and unmolested, let what will happen around them.”

The machinations of the factious Sikh leadership was ripe for consolidation, but that required exceptional character, bravery and power. All of that was delivered in the diminutive package of Ranjit Singh. Despite his physical stature he towered above the warring misls and subsumed the warring factions into his own through marriage, diplomacy and sheer force of leadership.

It was his ebullient Sikh force therefore that legitimised its own standing by taking Lahore in 1799 headed by the youthful and strong willed 19-year old chieftain Ranjit Singh. Over the next 40 years he would be a Maharajah, keep the British at bay, define Punjab borders from the Sind to Tibet and south almost to Delhi and die at the very height of his power. Ranjit Singh epitomised the 19th century Sikh king, and his rule remains the high point in any sense of Sikh nationhood or thoughts of sovereignty.

Life in the Sikh confederacies was tough; infighting was rife, murder and kidnapping common. Ranjit Singh would terrorise a mile into submission, kill its patriarch, marry the widows and subsume the name, its property, people and women into his own. Art was far from his mind.

In the early years of Ranjit Singh’s ascent to power in the Punjab miniature painting, as practised for the Mughals, had virtually lapsed and it was only in the Punjab Hills that artists painted for local princes and their courts. During the eighteenth century, the Sikhs had often interfered in Hill affairs. Early Sikh interventions had been largely opportunist. States were looted rather than occupied and no attempt was made to bring them under permanent Sikh control. In 1809 however, this policy had been abandoned. Sansar Chand of Kangra had been replaced as ruler by a Sikh governor under Ranjit Singh later Kangra was annexed. In 1811, Kotla, an offshoot of Guler and Nurpur, became a Sikh enclave and two years later, Guler itself was taken over.

The conditions for a new school of art to flourish in the Punjab Hills were in position; peace, prosperity and patronage. Bold and unencumbered by tradition the courtly Sikh art of the latter part of the 19th century is a powerful combination of robust colour, strong narrative and brutal honesty. Prompting one 19th century observer to describe the unique colour palette of the Punjab as “warm and rich and fearless”

In 1830, Maharaja Ranjit Singh was fifty years old. He had succeeded more than any other Sikh; He had tactfully subdued the misls, bullied his neighbours and out-witted the British he had united the Punjab and created a strong Sikh state. In this period of relative security and stability a potent mixture of a powerful and wealthy patron and rich artist traditions produced one of the most prolific periods of courtly sikh arts.

Historians are at odds as to why Sikh arts never embraced fully the sculpture form – either in diminutive ivory or as statues and monuments. The two arguments centre around a theological opposition or the evolutionary nature of the three dimensional form which often requires longer periods of sustained political stability to arise. Either way, nineteenth century representations of Ranjit Singh in three dimensions are incredibly rare. Three are known of in ivory and one is a silver centre piece of Ranjit Singh astride a war elephant now in Lahore Museum.

Possibly Ranjit Singh himself was acutely aware of his own physical appearance and resisted the temptation to commit this form to marble. It was after his death that successors keen to associate themselves with him or the new colonial masters wanting to re imagine the romance of his reign. This may well be the provenance on this piece being offered this October.

For a full story on Ranjit Singh by Christy Campbell and the bust click here. For further details on the auction on 9 October 2008 at Bonhams London please visit the Bonhams website. Punjab Heritage News will bring further information about the provenance of this piece when it becomes available from the auctioneers.