Variously described as “rare”, “impressive” and “imposing” the marble bust of Maharaja Ranjit Singh being offered by Bonhams is set to be the centre piece of this season’s Indian and Islamic sales for Punjabis around the world.

Variously described as “rare”, “impressive” and “imposing” the marble bust of Maharaja Ranjit Singh being offered by Bonhams is set to be the centre piece of this season’s Indian and Islamic sales for Punjabis around the world.

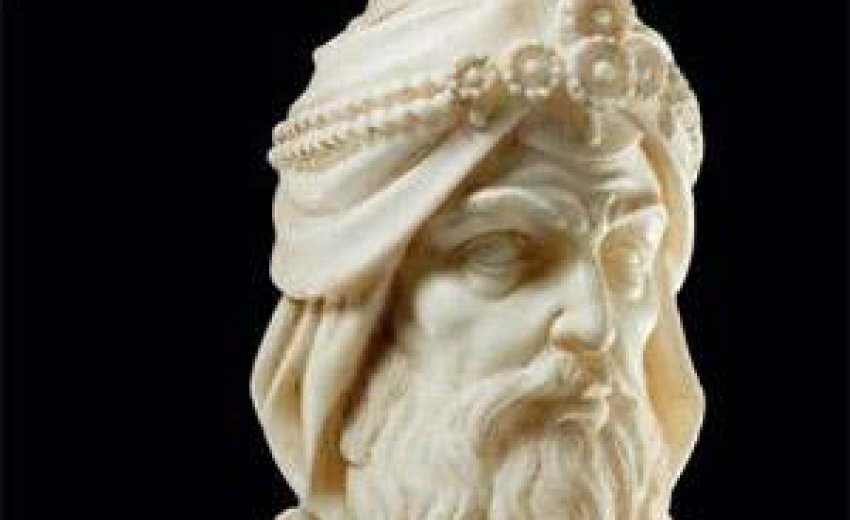

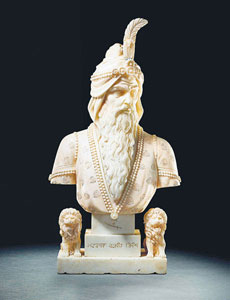

Standing at over 120cm tall, the bust is an imposing rendition of the Lion of the Punjab in a style that indicates a very strong European influence and presents a romantic view of the Maharaja so at odds with contemporary accounts of him. Emily Eden (1797-1869), the 7th daughter of the 14 children of William Eden, 1st Baron of Auckland and sister of George Eden who, as the 1st Earl of Auckland, was Governor-General of India (1836-1842) remarked after visiting Ranjit Singh in 1838: ‘He retained a perfect simplicity rather than plainness of appearance, while his chiefs and courtiers around him wore the most brilliant draperies and rich profusions of jewels. His manners were always quiet. He had a curious and constant trick, while sitting engaged in conversation, of raising one of his legs under him on the chair and then pulling off the stocking from that foot.’

When Emily Eden sketched the maharaja she tactfully painted his right side only – a deception used by Ranjit Singh’s court painters to disguise the effects of the paralysis that affected his left side and the deformities as a result of childhood small pox.

French botanist, Victor Jacquemont, a traveller in the Punjab from 1829 to 1832 described Ranjit Singh thus: 'He is a thin little man with an attractive face, though he has lost an eye from small-pox which has otherwise disfigured him little. His right eye, which remains, is very large, his nose is fine and slightly turned up, his mouth firm, his teeth excellent. He wears slight moustaches which he twists incessantly with his finger and a long thin white beard which falls to his chest. His expression shows nobility of thought, shrewdness and penetration.’

However the most cutting and brutal eyewitness description given was by Baron Charles von Hügel, who described him as 'Without exaggeration, I must call him the most ugly and unprepossessing man I saw throughout Panjab. His left eye, which is quite closed, disfigures him less than the other which is always rolling about, wide open, and is much distorted by disease.'

Bonham’s experts consider the piece a relatively late depiction of the Maharaja: 'The bust is unsigned and cannot be attributed to a known European or foreign sculptor, of which there were many working in the princely states. The marble is Indian in origin, and the historicising style, which was not seen in European sculpture until around 1870, would point to a date later than that. It is most probable that it was made for a wealthy or aristocratic Sikh patron by an Indian sculptor trained in the European tradition.' The style of the script at the bottom of the piece would validate this.

The sculpture which was acquired by the vendor's grandfather from a Sikh friend of a prominent family in Lahore before Partition is described as being 'full of hidden metaphors', the catalogue continues: 'The subject regally looks slightly to one side, the sculptor skillfully deflecting the viewer's gaze away from his blind left eye, which was caused by smallpox in childhood. The top tier of the pedestal is engraved in miniature with the symbols used in the battle standards of Ranjit's army, the khalsa. They are from the top down the double-edged sword or khanda, the circular ring or chakkar, and a curved sword or kirpan - half hidden by a medallion suspended from a festoon of pearls. The middle tier bears an inscription of the Maharajah's name in Gurmukhi. The lions flanking either side of the base signify the power and majesty of the subject.'

The detailed Bonham’s appraisal of the piece reveals other fascinating details: 'The execution of the design on the tunic, perhaps not as fine as the facial features, can be explained by the fact that these incised outlines were once probably inlaid with some form of coloured pigment or gilt, removed by a combination of many years of cleaning and a humid climate. It is also possible that some form of pigment would have been applied to the face as seen on European busts of the 19th Century, emulating the classical Greek tradition. From a perspective point of view, based on scale and the general carving, it is likely that the piece was designed to be set at height and to be seen only from the front or side, perhaps in a niche or rounded location - for private veneration rather than public display.'

For the full description of the sale including viewing times and auction dates Click Here .