BOOK REVIEW

‘The book is the most comprehensive, balanced, unbiased and objective account of the tragic happenings during Partition in the two Punjabs...’ - From A review by Pran Nevile in The Statesman.

Many books have been written on the partition, India’s ‘holocaust’, which led to the creation of Pakistan in 1947. There have been movies made out too. All the literature and movies using fact and fiction, highlight forced migration in the Punjab and the brutal violence that followed affecting 9 to 10 million. As regards fatalities the exact figure will never be known. It is estimated to be around one million. The end result was ethnic cleansing on both sides.

Ishtiaq Ahmed, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the Stockholm University, and a Punjabi Lahori himself, has chronicled these facts and must be credited with one of the more intensive works done on the Partition massacres and the division of Punjab.

The 700-plus pages of The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed unravels the 1947 tragedy through a series of secret British documents, including the Governor’s Fortnightly Reports (FRs) and some of the most exhaustive first person accounts of survivors who escaped from west and east Punjab with the help of their friends, most of whom belonged to the ‘other’ community.

Though other books have been published on Partition, Ahmed has an advantage over scholars from India and Pakistan: as a holder of a Swedish passport, his access is greater. In this book, for the first time indeed, factual eye-witness accounts have been brought out of the tragic happenings in the two Punjabs during 1947. He has been able to conduct extensive interviews of more than 200 survivors of the holocaust in Pakistan and India. Included are Sikhs and Hindus who managed to get away from west Punjab and Muslims who survived the bloodbath in the east, but ended up as refugees in their new homelands.

M Rajivlochan, in a review, writes, Ahmed “provides a theoretical underpinning to understand why people living peacefully for many generations can become so aggressive and hostile to each other all of a sudden.”

Ahmed has explained “the politicking that went on during the time of Partition… and the almost complete collapse of the administration that opened the way for the goondas of all communities to take over the streets and attack people of the other community. Their ferocity easily overwhelmed the good people who tried to help out each other and contain the communal conflagration.’

In the early 1940s, when the idea of Pakistan had been well mooted and in the air, no one quite knew what it stood for. Most certainly, no one had reckoned with what it would entail if Punjab were to be partitioned along with the division of India. Then, neither the Congress, Muslim League or the Sikh Panthic parties in Punjab could have envisaged that in their zeal to mobilise vote banks, they were a few years away from one of the most horrific genocides in history.

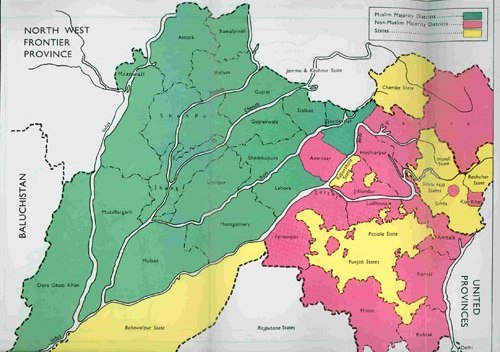

Punjab Census map of 1941 showing Muslim majority districts (green),

non-Muslim majority districst (pink) and princely states (yellow)

The British administrators had more acumen. In October 1944, Sir Bertrand Glancy, the governor of undivided Punjab, noted with despair in his Fortnightly Report (FR): “No one can deny the possibility of political unrest after the end of the war, but I can think of no more alarming menace to peace, so far as Punjab is concerned, than the pursuit of the Pakistan doctrine. Any serious attempt to carry out into affect this idea in Punjab with its bare Muslim majority and its highly virile elements of non-Muslims means that we shall be heading directly towards communal disturbances of the first magnitude....’’

Glancy was among the first who foresaw the future. His successor Sir Evan Jenkins witnessed and indeed presided over, even more disturbances and saw the gory drama as it unfolded, knowing that the outgoing and once-influential British administration was utterly powerless to stop Punjab from turning into a communal inferno, which in 1947 claimed anywhere between 500,000 to 800,000 lives with many hundreds of thousands displaced once the Radcliffe Award on August 17, 1947 had demarcated the boundaries between the two new dominions, India and Pakistan and the two new states of west and east Punjab.

Ahmed revisits old but pertinent questions. Could Louis Mountbatten’s ambition to be Governor General of India and Pakistan have averted the blood letting in that fateful monsoon of 1947? Were the Sikhs determined to ‘cleanse’ east Punjab of all Muslims so that Sikhs facing a similar fate in west Punjab could be accommodated there? Equally, did the Muslim League decide to get rid of all Hindus and Sikhs in the west so that Muhammed Ali Jinnah’s two-nation theory could be implemented on ground for an all-out Islamic state? Did Mountbatten’s decision to leave India a year in advance – August 1947 in place of the June 1948 – leave no time for the administration to get its act together and save lives? The Punjab Boundary Force (PBF), designed to enforce peace in the state, lasted a few weeks and proved to be totally inadequate to deal with the violence of magnitude unleashed by what Ahmed calls ‘political entrepreneurs’?

Pran Nevile writes in his review in the Statesman, “It is interesting to note that Jinnah in his statement published in Dawn dated 1 May 1947 argued that an exchange of population in Punjab would have to be effected at some stage. But the Congress and the Viceroy Mountbatten seem to ignored it In the meantime communal rioting was spreading like wildfire in Punjab. By the middle of June, Lahore was burning and there was a large-scale exodus of non-Muslims to East Punjab. The arrival of Hindu and Sikh refugees and their stories of horror, rape and brutal killing of men, women and children led to a devastating retaliation and the Muslim population of East Punjab began running away towards West Punjab. Neither the Congress nor Muslim League leaders bothered to visit Punjab at this juncture to stop this savage mayhem”.

The author makes a significant observation that Jinnah had issued a strong condemnation of the attacks on Muslims in Bihar but remained silent on the riots in the Punjab.

Ahmed’s interviews with survivors began in 1997 and continued till as late as 2011. Interestingly, as they reveal, Punjabis, who go back to their original places of birth – Muslims to east Punjab and Hindus and Sikhs to the west – receive an emotional welcome from their former tormentors, as if 1947 was just a minor blip in history. “The classic case in this regard was when the Pakistani High Commissioner to India allowed east Punjabis to come to Lahore to watch a cricket Test match in early January 1955. Thousands of Hindus and Sikhs accepted the invitation and they were received with unprecedented warmth and generosity,’’ writes Ahmed. In another account, Dr Khushi Mohammed Khan, a Muslim who escaped the knife in the princely state of east Punjab’s Nabha in 1947 and managed to reach Pakistan, says he now spends a month in good old Nabha since he first got a visa in 1979.

Pran Neville writes, “More than six decades have passed since the separation of two Punjabs. The generation which went through that ordeal usually dismiss it as a bad dream. Whenever the Punjabis from both sides meet their encounters have been very emotional. Prof. Ishtiaq Ahmed, a typical Lahoria by birth though from the next generation is a keen observer of this ethnic amity. I vividly remember the bonhomie at the Indo-Pakistan Mushairas during 1950s when Punjabi poets from the two sides with past association met one another. I fully endorse Ishtiaq's observation that the Punjabi identity remains a very strong part of the cultural make-up of the people”.

“So where does this leave us today? Britain departed from the subcontinent six decades ago”, writes Rajinder Puri, a veteran Indian journalist, born in Lahore, “But the colonial mindset of the divide-and-rule policy they bequeathed to the governments of India and Pakistan persists till today. Former Indian diplomat Mr. Moni Chadha recalled to the author of this book his experience when he visited his ancestral village in Pakistan. Without exception the people were overwhelmingly friendly. But the ISI security relentlessly hounded him wherever he went. The gulf between the government and the people could not have been starker. The myth that religion can be converted from a spiritual message into a political device to achieve consolidation is shattered in Pakistan. Although one fourth the size of pluralist India the polity of Muslim Pakistan is more bitterly divided between Shias, Sunnis, Pashtuns, Punjabis, Sindis and Mohajirs as they battle for turf and power. If people want to reclaim their cultural nationalism by normalizing relations between India and Pakistan the new generation must get rid of the political mindset that prevails in both countries. That implies a replacement of the prevailing political class and political culture. That would require nothing short of a democratic revolution. That in a real sense would be the subcontinent’s second freedom struggle.”

Ahmed’s book, which boasts of a distinguished bibliography, is in many ways an ode to Punjabiat. A must read for those interested in partition to understand how communities who live side by side for hundreds of years can suddenly, within a matter of weeks, become implacable enemies.

Ahmed held an interesting and highly appreciated Lund University’s Swedish South Asian (SASNET) lecture entitled "The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed: Unravelling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First Person Accounts" about the 1947 Partition of Punjab, on Thursday 2 February 2012. The lecture was based on Ishtiaq Ahmed’s book. The full presentation is available here.

----------------------------

VIEW : The bloody Punjab partition — II — Ishtiaq Ahmed

The thesis can be formulated in the following words as well: the partition of India was a necessary but not a sufficient basis for the partition of PunjabThe thesis I have established in my book, The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed (Oxford University Press 2012, Rupa Publications, 2011) is the following: if India had not been partitioned, Punjab would not have been partitioned. The Punjab partition took place because the Muslim League and the Sikhs could not agree on keeping Punjab united.

I, however, do not suggest that if India were partitioned, Punjab must also be partitioned. There is no logical necessity or inevitability involved in the two outcomes though without the first the second would not occur. The thesis can be formulated in the following words as well: the partition of India was a necessary but not a sufficient basis for the partition of Punjab. For it to happen we need to focus on the political dynamics underway in Punjab at that time.

Consequently, in my book, the partition of India is discussed to the extent it impinged on the politics of Punjab. It is not the main focus of the investigation but it is most certainly the necessary link to explain what happened in Punjab. The dynamics of the Punjab partition are analysed in depth and in great detail with the help of source material that includes the Punjab governors’ fortnightly secret reports from 1936 to when the rule ended in 1947; newspapers, especially for the period January 1947 onwards; more than 200 interviews with witnesses, survivors of attacks and perpetrators of violence. I have used the secret fortnightly reports of the Punjab chief secretaries to a much lesser extent because both these fortnightly reports cover the same issues. The advantage of using the governors’ reports is that they represent the observations of the main British officer in charge of Punjab. I have also used police reports for details on specific incidents.

Government reports did not cover all events. I have shown that in many cases incidents that have been very significant to the Punjab situation are not reported. The police reports are also not enough. Officialdom tends to report conservatively and can even remain quiet on many events because of the biases of those collecting data as well as the authorities not wanting to expose their own failures in quelling violence. Consequently, the evidence given by those who were there when things happened in the fateful period when Punjab was bloodied and partitioned and cleansed was collected. I travelled throughout the length and breadth of the Pakistani Punjab and the Indian Punjab, going to remote villages, talking to people who remembered anything from those days. It cannot be ruled out that the interviewees could have distorted the facts or confused them because of the enormous time gap since 1947. I had to choose those interviews I judged were reliable.

For the events taking place in Delhi and the United Kingdom, I have used the 12 volumes of the Transfer of Power that the British government prepared. I have also used secondary sources to put together the all-India context of the partition of Punjab and of Punjab as well.

The Sikhs demanded the partition of Punjab almost as a knee-jerk reaction to the Muslim League demanding in March 1940 the creation of Muslim states in the Muslim-majority northeastern and northwestern zones of India. The first name given to it was Sikhistan and also Khalistan, which in the 1980s became their slogan. However, unlike the Muslims who did have majorities in those two zones of the subcontinent, the Sikhs did not have a majority in any of the 29 districts of united Punjab. Moreover, they were only 13.2 percent of the Punjab population.

Consequently, if the Sikhs wanted to have a Sikh state, they initially needed allies who could support them to achieve the partition of India. However, at that time the Congress High Command and the Punjab Congress both were committed to keeping India united as well as Punjab and Bengal. At that time, the ‘consociational’ model of power sharing developed by the Punjab Unionist Party provided stability and peace in Punjab. The Unionist Party was opposed both to the partition of India and of Punjab. The Muslim League wanted to have the whole of Punjab in a Pakistan created out of the partition of India.

The last premier of united Punjab and leader of the Unionist Party, Sir Khizr Hayat Khan Tiwana, proposed that irrespective of whether India was partitioned or not, Punjab should seek separate membership in the British Commonwealth as a dominion in its own right. That proposal suited neither the Congress nor the Muslim League, not even the British.

Since the Sikhs and not the Punjabi Hindus made the demand for the partition of Punjab, the puzzle why the Muslim League and the Sikh leaders failed to agree to keep the province united has to be solved. This is the main concern of my investigation.

By rejecting the Cabinet Mission Plan of May 15, 1946, the Congress was prepared to pay the price in terms of a partitioned India to consolidate India as a cohesive and unified state, albeit reduced in size so that Pakistan as demanded by the Muslim League could emerge as a separate Muslim-majority state. On March 8, 1947, the Congress decided to support the Sikhs on the partition of Punjab as a means to checkmate Punjab as a whole going to Pakistan. A united Bengal was also out of the question for the same reason in the aftermath of the Great Calcutta Killing of August 1946.

It is most interesting that in July 1947, the counsel for the Muslim League, Sir Muhammad Zafrullah Khan, pleaded before the Punjab Boundary Commission that defence and security requirements were such that the border in the Punjab should be drawn on the Sutlej — away from Lahore. The same logic informed the Congress strategy on partition — that is, to keep the border as far away from Delhi as possible — both in Punjab and by the same token in Bengal too. All this is systematically presented in my book. (To be continued)

Source#####

The writer has a PhD from Stockholm University. He is a Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Stockholm University. He is also Honorary Senior Fellow of the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. His latest publication is The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed: Unravelling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First-Person Accounts (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2012; New Delhi: Rupa Books, 2011). He can be reached at [email protected]

#####

View: Part I - continued

I am not a hagiographer of any idol, icon or saint. Hagiography is reverential homage to a cult figure, irrespective of what he has said and done

Mr Yasser Latif Hamdani’s comments on my book, The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed (Oxford University Press, 2012) published in Daily Times on June 16, 2012 belittle and scandalise my work. He writes: “For all his barely concealed contempt for Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Pakistan demand, the central thrust of Ishtiaq Ahmed’s argument is that the tragedy of hundreds of thousands being butchered happened after Congress insisted (my emphasis) — and the Sikhs leaders supported (my emphasis) the Congress on that — on partitioning Punjab.”

A more misleading description of what I have done and demonstrated in my book cannot be imagined. I have argued just the opposite: the Sikhs demanded and the Congress belatedly supported them on the partitioning of Punjab. He has tried to occupy the high pedestal of a devotee of Jinnah, a defender of the Two-Nation Theory, a guardian of Pakistan, as if there is a dearth of Pakistani equivalents of Knight Templars.

Mind you, Hamdani’s charge sheet is not based on what I have written in the Punjab book, because nowhere has he shown this in his article. It derives from his general opinion about me.

In India, scores of scathingly critical works on Gandhi and Nehru have been published. Much to the chagrin of the Congress Party, some prominent Indians have recently in their books praised Jinnah to the skies and condemned Nehru and Gandhi. It is testimony to the strength of their political culture and the resilience of their political system. People who have played a prominent role in history will always be an object of scrutiny. Only fascist, fundamentalist and totalitarian systems are based on the cult of infallible leaders. These systems suppress free discussion and debate but they cannot do it forever. This we all know.

A review of my book by Mr Imran Kureshi was published in Daily Times on March 21, 2012. In that he had concluded just the opposite of what Hamdani alleges. Reviews of my book have been published in the many leading dailies and other publications too. In one daily, a discussion on it has taken place over several weeks. In an Urdu-language weekly, and some dailies, reviews have appeared too. They are unanimous in appreciation of my objectivity, strict impartiality and scholarly responsibility.

Through painstaking, unprecedented research, heavily documented by official documents, newspapers and hundreds of eyewitness accounts, I have shown that after the Muslim League demanded the creation of separate Muslim states in its Lahore Resolution of March 23, 1940, the Punjab Sikhs began to demand a partition of Punjab.

On the other hand, the Congress wanted a united India, and struggled for it from December 1929 onwards when it gave such a call in its famous Lahore session. Its leaders and cadres filled British jails for years. The May 1946 Cabinet Mission Plan was fraught with risks the Congress was not willing to take, notably one that every 10 years, the three groups of A, B and C could choose to opt out of the federation or even individual provinces could do so. Two, the fourth group outside them, the princely states could establish direct relations with external powers. It could mean the British being invited to remain with troops in those princely states; thus going out by one door and returning by another.

Regarding a consociational arrangement between the Congress and the Muslim League, it was a non-starter from the outset. Whatever ‘trust’ hitherto existed between the Congress and Muslim League rapidly depleted after the 1937 election. For the consociational model to succeed, a number of preconditions have to be fulfilled. Of these, the most pivotal is a high degree of cooperation between different communal leaders to counteract separatist tendencies. That precondition was conspicuous by its absence from Indian politics since March 1940. At most a coalition government could have been formed. It was tried when an interim government was formed on September 2, 1946. The antagonism that marked relations between the Congress and the Muslim League ministers is too well known to deserve elaboration. Therefore, a consociational government was out of the question.

With regard to Punjab, an even more crucial fact to be noted is that the Akali Sikhs and the Indian National Congress were estranged parties in Punjab until as late as 1945. During the Quit India Movement of 1942, their differences became even wider, because while the Congress wanted the British to leave India, the Sikhs who were employed in disproportionally large numbers in the Indian army were against it. The Congress’ support came for the partition of Punjab only on March 8, 1947.

Consequently, the research puzzle the book seeks to solve is the following: why did the Sikhs, who were essentially a Punjabi group with their religion and history rooted in Punjab, opt for the partition of the province? What strategic mistakes did the Muslim League and Jinnah commit that the Sikhs did not join forces with them and kept Punjab united? A united Punjab — even if India were partitioned — would have served Sikh interests optimally. These questions I will address in my column next Sunday.

In my book, I criticise Gandhi and Nehru where I believe they were in error. I duly acknowledge that Jinnah made a number of attempts to win over the Sikhs but such efforts came too late. I have shown that Sardar Patel was involved in financing bomb factories. He told the Sikhs, “Qatal kar do” (Kill them [Muslims]). He told the Hindus of Jullundur to kill and drive out Muslims, thus reversing Jawaharlal Nehru’s instruction given to them a few days earlier to protect the Muslims. I have quoted Begum Shahnawaz who has asserted that Nehru’s personal intervention in Batala in August-September 1947 prevented a slaughter of Muslims by armed Sikh jathas (groups). Mahatma Gandhi saved thousands of Muslims in Delhi in September 1947.

As a scholar, my only responsibility is to conduct open research, devise a replicable method and make theoretical inputs that any other researcher can apply to the source material and decide if what I say is plausible or not. I am not a hagiographer of any idol, icon or saint. Hagiography is reverential homage to a cult figure, irrespective of what he has said and done. Most works of Pakistani authors on Jinnah are hagiographical. Scholarly analysis that looks at his role in history in an analytical manner is necessary to restore him to the world of human beings with all the strengths and weaknesses of human beings.

Source