|

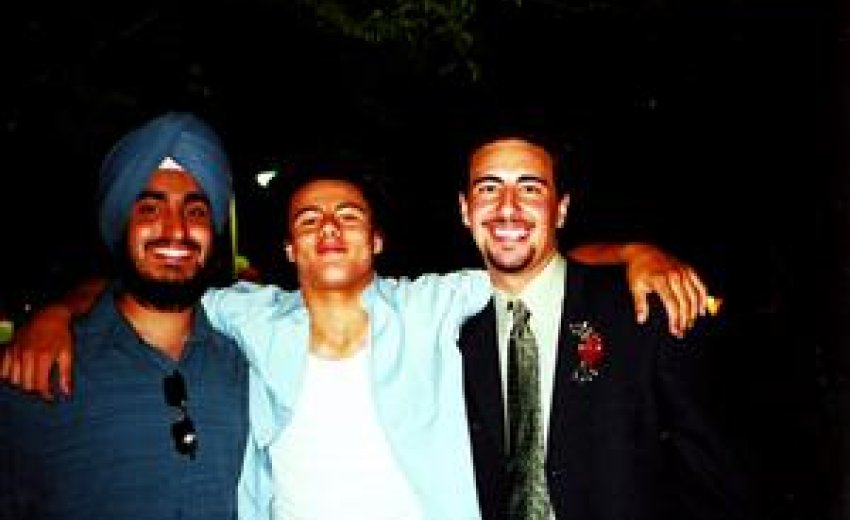

| Tejpal Sekhon, ‘02, with friends Najib Benouar, ‘02, and Nasson Boroumand, ‘01, celebrate at the 2001 graduation. - Julie Nelson |

When freshman Jaspreet Gill first donned the sacred Sikh turban—known as a pagri - at Franklin Elementary School, he was 13 years old.

Instantly his friends began acting differently towards him.

“People started laughing at me and spreading rumors,” Gill said. “They said that I hid knives in my turban.”

“I was kind of expecting it (since) I’m the only person who was a Sikh at my old school, and I’m the only Sikh at this school as well.”

According to a Sikh Times article, in September 2011, “over one thousand documented hate crimes (had) taken place, ranging from verbal abuse to racial profiling, battery to murder.” Many of these crimes were committed towards Sikhs due to common misconceptions about the turban, the article said.

Sikhism is a monotheistic religion founded in the Punjab, a region of northwestern India and Pakistan, in the 15th century by Guru Nanak.

It was founded to cure the social injustices—such as the Hindu caste system—present in Indian society.

It then progressed with the teachings of 10 successive gurus—the last teaching being their holy scripture “Guru Granth Sahib.”

It was through these gurus that the Sikhs were taught to wear the turban, Tejpal Sekhon, ’02, said.

Tejpal and his brothers, Ajaipal, ’00, and Shabeg, ‘04, were the first Sikhs to attend Country Day.

Ajaipal was the first. Many of the faculty and students at the time had never met a Sikh before. “People were generally curious,” Ajaipal said.

So he informed anyone who asked about why he covered his head or anything else about his culture and religion.

According to Tejpal, Sikhs cover their heads because they believe heads encase minds, and to cover the mind is to “show respect to God.”

When the Muslim Mughal empire ruled India from the 16th to 19th centuries, the turban was a sign of royalty. Only Muslims wore them. All non-Muslims were forbidden from wearing the pagri.

“Our ancestors fought for the right to wear it,” Tejpal said.

The Sekhons have been wearing the turban for as long as they can remember.

When Tejpal was a child, he wore a patka, the same style of turban that Gill wears to school. The patka is a rectangular piece of cotton—approximately a foot by a foot and a half with four laces—that wraps around the head like a bandana and is very form-fitting, Tejpal said.

Young boys usually wear this type of turban, and most Sikhs wear patkas for sports.

When Tejpal played basketball he’d wear a ramaal—a square piece of fabric that mostly covers the hair.

He wore this instead of the patka because he didn’t want to start any trouble.

“I thought that the league wouldn’t let us wear the patka for the same reason they wouldn’t let people play with bracelets, earrings or (other) jewelry,” Tejpal said.

Adults wrap larger, more formal turbans, known as dastars, around their heads—approximately 10 inches wide and 2-3 yards long.

To the Sekhons, the donning of the dastar was a sort of coming-of-age.

“Our father told us it was the next step to growing up. It was the turban we’d wear as adults,” Tejpal said. “I didn’t know how to tie it, so my father tied it for me before I went to school.”

Although It is encouraged for Sikhs to cover their heads, the only time it’s absolutely necessary is in the temple or around the holy book.

In fact Gill’s father, doesn’t wear one, and he cuts his hair.

“It’s optional,” Jaspreet said. “It’s not like if you don’t keep your hair, you’re not a Sikh. Sikhs can cut their hair if they choose.”

However, Tejpal believes that it is important to grow out one’s hair and wear a turban.

“If there is someone that doesn’t keep their hair, and doesn’t wear the turban, they aren’t following the dress code our Gurus have given us,” he said.

Gill chooses to grown out his hair and cover it with a turban because he believes it’s a part of being a Sikh and a way to identify oneself.

“In the martial arts (studio) I go to, there’s a grand master who goes all around the world and meets all these people,” he said. “And the only person he can remember is me because I’m the only one he knows who wears a turban.”

Although the turban is one of the most important articles of the Sikh faith, it is not the only one.

Orthodox Sikhs must adorn the Five K’s: Kesh, Kangha, Kara, Kachera and Kirpan.

The Kesh is uncut hair covered by a turban.

The Kangha is a comb which, according to Tejpal, represents the Sikhs’ good hygiene.

The Kara is a steel bracelet worn on the wearer’s dominant arm, which reminds the Sikhs of the advice of their Gurus, Tejpal said.

“It represents the universal oneness of God and how life is never ending.”

The Kachera, according to Tejpal, are special boxer shorts that allowed Sikhs to move freely in battle. The Kachera currently represents their shame and humility.

The Kirpan — the most controversial of the Five K’s—is a dagger Sikhs keep on their bodies.

When Sikhs were told by their Guru to wear the Kirpan, they were living in harsher times; the dagger was used for self-defense and the defense of the defenseless.

Tejpal and Ajaipal keep a more ceremonial one-inch Kirpan around their necks.

Gill, on the other hand, wears a three-inch-long Kirpan when he can. But he doesn’t wear it at school.

The Kirpan has been surrounded with controversy for years.

“I know there have been cases here in California (like) a man who was arrested for having (the Kirpan),” Tejpal said. “It was complete ignorance on someone’s part. (His Kirpan) wasn’t concealed or anything.”

Gill has also known people who got in trouble with their Kirpan.

He once had a friend in Yuba City ignored the dagger’s main purpose: the protection of the weak.

“(Once some) people were teasing him, and he pulled the dagger out,” Gill said. “He shouldn’t have done (that) because we’re supposed to be able to defend ourselves without using the knife. We’re only supposed to protect the weak with it.”

When Gill was in a similar situation , he acted much differently.

“There was a time where these guys were getting a bit physical with me and teasing me,” Gill said. “I was tempted to use the dagger on them, but I didn’t.”

|

|

| Ajaipal Sekhon in 2000. (Photo courtesy of Julie Nelson) | Michael Haleva, ‘05, teacher Ron Bell, Shabeg Sekhon, ‘04, Kelsey Lyon, ‘04, Eric Norton, ‘04, and Joe Flynn, ‘04, relax in front of Geeting Hall.By Julie Nelson |

Ajaipal also faced discrimination when the soccer team played Wilton Christian in 1999. “(Wilton) had never seen something so exotic like a Sikh,” former coach Tibor Pelle said.

The referees told Pelle that they wouldn’t allow Ajaipal to play because they thought he was hiding a knife on him.

So Pelle said that either they’d allow Ajaipal to play or they were going to have a religious lawsuit slapped on them.

In the end they let him play.

According to Tejpal, racism increased after 9/11, and he was unable to be out after dark.

“We got a lot of people yelling at us, staring at us and cursing at us,” he said.

Tejpal was driven off the road while commuting from Yuba City to Sacramento the day after 9/11.

“The guy saw me (and) started yelling, and drove me off the road,” Tejpal said. “I definitely knew it was because I had a turban and beard.”

Since 9/11, screening procedures have been increasing. In 2007 the Transportation Security

Administration put in place a policy for a second screening of “bulky” clothing.

A Sikh’s turban now must be patted down by either a TSA agent or the Sikh himself with an agent in attendance.

“I think it’s completely pointless,” Tejpal said. “You can hide more under someone’s T-shirt, pants or bra than (under) a turban.”

But Gill disagrees.

“It’s reasonable. Not only do Sikhs wear turbans, Muslims wear turbans,” he said. “Since (Muslims are) the main source of terrorism, it makes sense for them to pat everyone.” Gill also said that there is a way to tie a turban so that there’s room for weapons or other dangerous devices.

Ajaipal is apathetic towards the policy.

“(They’re) just doing their jobs,” he said.

When Ajaipal was young, he’d get into fist fights to defend himself and others who were being verbally attacked at his old public school.

Gill chose a more peaceful approach. He gave his history teacher a copy of “Cultural Safari: Sikhism” to explain the turban to his fellow classmates.

But he didn’t have to do that this year, when he transferred to Country Day. The Sekhons had already paved the way.