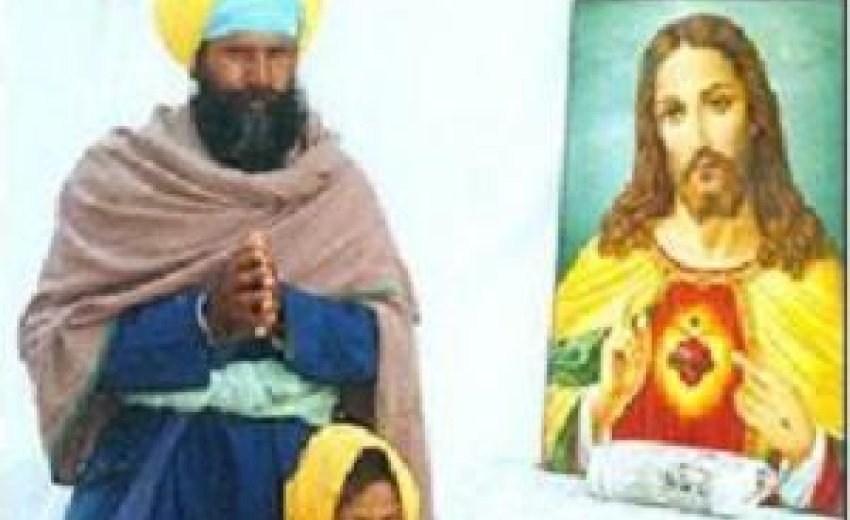

I must confess that I was appalled when I first read reports of Christians targeting Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and other regions of India for massive conversions to Christianity. Punjab is the land of my religion - Sikhism - and that bothered me even more.

I must confess that I was appalled when I first read reports of Christians targeting Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and other regions of India for massive conversions to Christianity. Punjab is the land of my religion - Sikhism - and that bothered me even more.

How could they do this, I wondered? Is it even legal in India? Isn't there a law against conversions on the books in India?

Then I thought some more.

Muslims invaded India a millennium ago, and uncounted millions converted to Islam - many at the point of a gun. During an earlier era, millions escaped the stultifying embrace (change that to a boa's death-grip) of caste-riven Hinduism by becoming Buddhists - until a resurgent Hinduism decimated Buddhism in India.

Sikhism arose in India just over 500 years ago. Many Hindus and Muslims flocked to its progressive ideals and became converts. The distinct identity of Sikhism does not sit well or comfortably with many Hindus, even today.

St. Thomas, one of the original apostles, is reputed to have taken Christianity to India; Brahmins perceived him a danger to Hinduism and probably killed him there.

Punjab has had two prominent and historic citadels of Christianity - in Ludhiana and Batala. The British, perhaps, felt then that if Punjab could convert to Christianity (much as a large swath of South India had done) then surely Punjab, and even greater India, would remain securely within the British Empire, maybe forever.

This is not the time or place to delve into the colorful history of the Holy Roman Empire, but don't forget that Christianity and political power were rarely and only briefly separate and distinct. Until recent times, they were seamlessly merged. The founders of the United States did separate church and state, but the minds of George W. Bush and many of his ilks continue to conflate the two.

When, after the British annexation of the Sikh Raj just over 100 years ago, Christian proselytization raised its ugly head in Punjab, it was then that Sikhs woke up with a start.

This marked the beginning of a reform within Sikhism and the rise of the Singh Sabha. This movement effectively put a stop to Christian conversions in Punjab. This extraordinary achievement came not by protest and public display of angst, but by a methodical and remarkable awakening amongst the common people led by the Singh Sabha.

Conversions have been happening all over the world, including Punjab. They are not likely to cease; after all, there is a smorgasbord of religions in the growing and global free marketplace out there.

But why all this emphasis on the small state of Punjab?

Keep in mind that there is real geopolitik at work here. The global realities are such that, to a West under siege, a powerful India is the only Asian counterweight to an increasingly muscular China and, as a nuclear power, the only one that can stem the rising tide of Islamic fundamentalism at the same time.

Punjab sits astride what has been the passageway to India for centuries, and it also abuts Kashmir as well as a nuclear Pakistan, two powerful powder kegs ever ready to blow. India today is a critical geographical and political presence. Strategic imperatives and economic interests of the Western world are closely intertwined with the realities of Punjab. For the Western nations, a Christianized Punjab is perceived as a potential bulwark and a dependable ally - not unlike the way Timor has recently been cultivated in the heart of Islamic Southeast Asia.

We Sikhs, like Hindus and Buddhists, welcome converts but do not go out to actively proselytize others, and nor does Judaism. But the two derivatives of Judaism - Christianity and Islam - seem absolutely convinced of the self-righteous idea that no human can be saved but by joining one of their movements.

Keep in mind that this hubris not only extends to these glorious traditions when they view others, but to each other as well. The only saving grace now is that conversions are no longer at the point of a gun as they used to be, and believers of other faiths not burned at the stake as they once were.

Sikhism, on the other hand, refuses to beguile people with promises of unmatched pleasures in the here and the hereafter if they join the faith, or frighten them with the eternal wrath of God if they don't.

Besides the "carrot and stick" idea of eternal reward and punishment, how does Christianity sell its product and go about converting people?

And from this we can learn.

There was a time when political power sustained the Christian message. And now, again, with the political ascendance of George W. Bush and the evangelicals, this model seems to be enjoying a second life, but with a difference. Now it is not raw power that comes from a gun, but it is economic colonization of a people.

Much of the world is still developing and has a long way to go before it can even feed its own people, much less turn their lives sublime. India is a prime example.

Most churches come with schools. People flock to them because education promises to lead them out of poverty. Many of my readers today, I am certain, are grateful products (alumni) of such schools, not because they fed us Christianity, but because they were academically good. They empowered us.

Many Christian centers also provide adult education, vocational training centers, a meeting place and often, if limited, medical care. These remain luxuries in contemporary Indian rural society, but they are essential to survival; they are the fundamentals of a life of hope.

On the other hand, the caste system still continues to define Indian society by placing Indians in a rigid hierarchy where every aspect of their life is defined for them, and where every move upwards meets a strongly resistant, almost unbreakable glass ceiling. This is doubly true of India's rural millions - the majority of the Indian population.

Christianity has found a niche in India by refusing to pander to the Indian caste-system. Imagine how liberating that idea is to a low-caste person - an untouchable - in Indian society.

Rejection of the caste-system and repudiation of the second-class status of women were cardinal lessons that the Gurus hammered into us when they made us Sikhs. It took them over 200 years to do so, but hardheaded as we are, these are not lessons that are etched in our bones yet. Our ties to the traditional Indian practices still bind us and control us.

I have to marvel at the management of this project of bringing Christianity to Punjab by the missionaries - I mean one can't but admire their technology and farsighted goal of building a church in each postal zone. This really means placing a simple church within walking distance of every Punjabi.

This reminds me of the FDR goal, following the depression era of the 1930's, of a chicken in every pot and a car in every garage as a way to focus on economic recovery of the United States.

Isn't a church in every village, along with its developmental services, going to be more effective than building huge marble mausoleums, admittedly with Guru Granth in each, but inaccessible to any but the rich? But this is what we commonly do when we build gurdwaras, and then we rue when they seem to have so little lasting impact on the lives of ordinary Sikhs.

Remember when gurdwaras were centers of education and community centers? People will go where they can get the help they need.

Remember the Singh Sabha? In Punjab or away from India, anger needs to be harnessed and channeled; progress methodically pursued and measured.

We know that Sikhi is a beautiful system of how to design a life. But like a salesman who is hawking GM cars in this day and age, we are supremely insecure and uncomfortable driving the product ourselves. If the GM salesman is personally lusting after the BMW, what is the probability, then, that he would sell well?

It seems to me an unassailable truism that all efforts must start with the individual. We can never teach others what we ourselves do not know. So that's where we start. That is essential but not sufficient to stem the rot.

One cannot miss the fact that the leaders of the church-building initiative in Punjab seem to be from the local areas. They are Punjabis; certainly at the people-to-people level; they are not imported from United States, Canada, Great Britain or similar lands with a stake in the program.

So, I would say, look not to the political structure of Punjab, the SGPC or the dysfunctional Sikh institutions in the Diaspora, for lighting our path. Think not of people (Sikhs or otherwise) coming from elsewhere to come and save us. We tried that once with importing Dayanand to Punjab at the beginning of the Singh Sabha, and he was a disaster who haunts us to this day.

Keep in mind, as a moral lesson, the fate of Gyani Ditt Singh - a stalwart of those days - whom we would not fully embrace because he had come to us from a "low caste". Look not to laws in India or elsewhere to come to our rescue. This is not their job.

A measured, sustained response is necessary; the race is not necessarily to the swift.

Some backbone needs to replace the siege mentality that often surfaces whenever we sense danger. The first step is a focus on self-development.

The second step would be inevitable, once the first is initiated, and the two will progress in tandem.

Institutions will and need to crop up to reverse the rot.

A new Singh Sabha!

Can it be done? Why am I optimistic that it will be done? Because history and Sikhi tell me so. We have been down that road many times before. It's a battle that must be fought; it is a battle that will be won.

A sports icon of yesteryear, Billie Jean King, who put women's tennis on the map, and revolutionized the place of women in professional sports, has just written a new book, Pressure is a Privilege.

Isn't that how we define "Chardi Kalaa"?

The book's title says it all. All we need to do is to transform a pressing matter into an opportunity.

Recommends Guru Nanak (GGS, p 474): "aapan hathee apnaa aape hee kaj savariyae" - he asks us to put our minds to grappling with, and resolving, our own needs.

The author, Inder Jit Singh, is a professor of anatomy at New York University. He is on the editorial advisory board of the Calcutta-based periodical, 'The Sikh Review' and is the author of four books: 'Sikhs and Sikhism: A View With a Bias,' 'The Sikh Way: A Pilgrim's Progress,' 'Being and Becoming a Sikh' and 'The World According to Sikhi.'

[email protected].

Opinion By I.J. Singh