Bhāī Tārū Singh – Blazing Poppy

There are historic events and deeply moving human tragedies that can never be forgotten, but flow through the centuries like the waves of the sea and, day after day, break on the shore of the present day. One of those whose pain is still felt by human beings long after their life has ended in a shocking way is Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī. Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī’s life began in October 6, 1720, when he was born to his father Bhāī Jodh Singh and his mother Bībī Dharam Kaur in the village of Phūlā near Ammritsar. When Bhāī Jodh Singh followed the call to war to defend the Sikhs‘ freedom against the Mughals, he did not return home, so that his wife was now on her own with two children, Tārū and Tāro. But Bībī Dharam Kaur was a women who in spite of her great loss did not quarrel with VĀHIGURŪ JĪ – for her husband had fallen so that the desire, felt by all of the Sikhs, of being able to freely practice their religion could be fulfilled one day. So she brought up her two children without bitterness and with a heart dedicated to VĀHIGURŪ JĪ, and as she was an educated woman, she was also able to teach the two half-orphans Gurmukhī.

Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī’s life began in October 6, 1720, when he was born to his father Bhāī Jodh Singh and his mother Bībī Dharam Kaur in the village of Phūlā near Ammritsar. When Bhāī Jodh Singh followed the call to war to defend the Sikhs‘ freedom against the Mughals, he did not return home, so that his wife was now on her own with two children, Tārū and Tāro. But Bībī Dharam Kaur was a women who in spite of her great loss did not quarrel with VĀHIGURŪ JĪ – for her husband had fallen so that the desire, felt by all of the Sikhs, of being able to freely practice their religion could be fulfilled one day. So she brought up her two children without bitterness and with a heart dedicated to VĀHIGURŪ JĪ, and as she was an educated woman, she was also able to teach the two half-orphans Gurmukhī.

Around 1745 the Pañjāb was ruled by Zakarīā Ḳhān. He was a monster that plotted day and night on how to do mischief and had chosen the Sikhs as the victims of his endless thirst for blood and his delight in torture. To escape the tyranny of Zakarīā Ḳhān and his human bloodhounds most Sikhs had taken flight, and many of them had only been able to take their most basic possessions with them, while some had nothing at all. They had fled to places where they were relatively safe from Zakarīā Ḳhān’s murdering and plundering hands - to the deep jungle, the remote plains, the barren desert and the pathless mountains. They needed more than just food for survival, and what they needed was provided by some courageous Sikhs who had remained in the villages in spite of all the adversities, leading a quiet and very reclusive life so as not to attract attention. And just as quietly, they cultivated their fields and fed their buffaloes to get some milk.

Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī, who had received Ammrit through Bhāī Manī Singh Jī and was deeply impressed by the older man‘s personality and his knowledge, like his mother and his sister belonged to the band of the charitable who were able to live in accordance with one of GOD‘s mercies: Never think of yourself only. Most of what they gained by farming was taken from them by Zakarīā Ḳhān‘s tax collectors, who regarded the Sikhs as nothing but animals on two legs.

Although there were many times when the three of them had hardly enough food for themselves, they again and again kept going without meals to support the Sikhs living in the wilderness, so that the struggle for the liberty of all their brothers and sisters in faith could be continued. All of this had to happen in strict secrecy, for they were "traitors to the government" and this was always punished by torture and death. Every time Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī and his sister Tāro Kaur Jī brought food to their brothers' hiding-places, they put their lives into the scales of death.

The Mughal officials expected that the Sikhs remaining in the villages would not only be reported by Muslims, but also by Sikhs themselves, at the slightest indication that they supported the rebels. It is certain that this happened in some cases, but the historical sources report that in Bhāī Tārū Singh‘s ancestral village and the surrounding towns Sikhs and Muslims lived in peace with one another, helped each other in everything and were magnanimous towards their neighbours. Those Muslims regarded Zakarīā Ḳhān‘s evil wrongdoings and those of his subordinates as disgusting. One day, as a result of this friendly togetherness, Rahīm Bakhś, a Muslim, deeply troubled and very agitated, came to see Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī and to ask him for help. His sixteen year old daughter Salmā, the most delicate of all flowers, had been taken from her familiar surroundings and abducted by the Mughal commander of Paṭṭī. Rahīm Bakhś said that, as he knew that he was in the right, he had already seen Zakarīā Ḳhān and entreated him to have his daughter set free, but in vain. He had been lucky to escape unscathed, but he was afraid that the Mughal commander would take his tender flower-like Salmā into his garden to first gather her blossoms and then let her wither.

The worried father had hardly finished his anxious complaint when Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī went on his way to assemble some fearless Sikhs from the area. Together, they stormed the fortress of Paṭṭī to call the brute to account. The abductor was killed in the attack. But the lovely and flower-like Salmā was saved.

Not each and every historical source can fill the bowl of knowledge that those thirsting for understanding bow down to. But someone has decided that this very beaker we are now writing about was to be filled to the brim so that it pours out its drops, one after the other, so that these drops can be turned into words. It could not remain hidden for long that Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī and his sister Tāro Kaur Jī visited their brothers in the barren wilderness in order to facilitate a relatively bearable life for them. It was the arch-enemy of the Sikhs, Harbhagat Nirañjanīā, also known as Ākil Dās, who found out what they did by constantly spying on them. When he knew what the siblings did, he immediately went to Zakarīā Ḳhān to report them. He got what he wanted: He was given a troop of twenty armed men with whom he went to Phūlā to arrest Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī and his sister.

When Harbhagat Nirañjanīā and his henchmen seized the two, this created considerable stir and made the villagers assemble in front of Bhāī Tārū Jī‘s house to protest the injustice. Ākil Dās was surprised by the way these Muslims supported their Sikh brethren, but the heart of a man whose lifeblood is evil is harder to melt than a stone. He remained unmoved and led his prisoners away, and their mother was not the only villager that shed bitter tears.

As Harbhagat Nirañjanīā passed the village Bhaḍānā with his captives, some brave Sikhs who wanted to liberate the siblings by force barred his way. Bhāī Tārū Singh was deeply moved but refused, explaining to them that his and his sister‘s freedom would mean their own ruin, and that this had to be averted for the sake of the community‘s future. But he allowed some compassionate villagers to gain the release of his sister Tāro Kaur for a ransom they had collected in a hurry. He could not stand the thought that his beloved little sister was frightened and was likely to be dishonoured and then brutally killed.

Once in the prison at Lāhaur, Bhāī Tārū Singh was immediately subjected to torture, so that he would confess to having supported the outlaws and therefore being a traitor to the government. In addition, his torturers wanted him to accept Islām. But violence did not get the hangman's assistants anywhere; they were not equal to Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī‘s strength of mind. Finally, they dragged him in front of Zakarīā Ḳhān, who looked at the half-naked Sikh standing in front of him without showing any emotion. He looked at Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī‘s well-shaped muscular body, which was covered with the gaping festering wounds that the instruments of torture had inflicted upon him, with his gaze finally coming to rest on the noble, expressive face, which was framed by a long dark beard. In this face he saw two gentle brown eyes which contained nothing of the things that filled his own soul, but radiated only a deep humility towards his fate and therefore towards his GOD. But Zakarīā Ḳhān refused to cast off his blindness and started talking at Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī:

"You are a strong man bearing up against pain very well. We could do with a man like you in our ranks. If you accept Islām and join us, you will be set free immediately. The most skilful physicians will attend to your wounds. You will exchange the torture chamber for princely apartments with lovely women waiting for you. But the best thing will be waiting for you after your life on this earth, for you will live in paradise forever and enjoy its delights."

Bhāī Tārū Singh answered: "I believe you when you tell me that my life on earth will be splendid, but what happens after my death? How do you know that as a Muslim I will life in paradise and never die? Do you know someone like that?" he finished with a little sneer.

Zakarīā Ḳhān remained silent.

"So, if I have to die in any case", Bhāī Tārū Singh continued,” why should I quit my GOD who through his religion of Sikhism teaches me to honour all human beings and all religions? And I believe that your GOD does not regard this matter in any other way, for HE is mighty."

Zakarīā Ḳhān remained silent.

"You keep silent. And you do so because you don‘t care about your GOD and your religion, for you have neither one nor the other. And you refuse to accept that if GOD had wanted me to be a Muslim, he would have had me born into a Muslim family."

Zakarīā Ḳhān kept remaining silent, but the realization ran through him like a violent flash: The prisoner in front of him was the chained lion, while he, Zakarīā Ḳhān, was nothing but a small blowfly asking the king for something. And he was deeply angered by this realization. His anger ate away at him and gnawed at his entrails. He thought about a terrible vengeance that might yet make the unfaltering man in front of him yield. Maybe it was while he was creeping around Bhāī Tārū Singh that his attention was caught by the Sikh‘s unravelled hair that ran down his back in long braids. The Ḳhān had an idea that could not have been any more abominable: "I see that you are as stubborn as all you vermin are. But I am generous and willing to forgive. I give you one last opportunity to convert to Islām and be freed. And let us cut off your long hair as a sign of your sincerity."

"My hair belongs to my GOD. You will leave my hair alone, even if it costs my life."

At this the Ḳhān started laughing boisterously. Still laughing, he called for a barber to cut off the jet black magnificent hair. But the barber was an honest man, and as cold sweat started pouring down him and his hands, which normally were so steady and nimble, were shaking uncontrollably, he was not able to carry out his task. Zakarīā Ḳhān shooed the barber away angrily and had a shoemaker fetched, who first of all was ordered to hit Bhāī Tārū‘s head with a shoe. What an ignominy! When the shoemaker finished hitting Bhāī Tārū‘s head, Bhāī Tārū looked into his tormentor‘s eyes and, penetrating them deeply with his gaze, said to him in a quiet voice:

"The time will come when you ask that what you did to me will be done to you. Your hour, truly, will come just a little later than mine. Stop what you are doing! Repent, while there is still time."

It was as if these words had emanated from another, more elevated world, in order to make Zakarīā Ḳhān leave the path of violence. But alas, Zakarīā Ḳhān was blind to the hand of mercy stretched out towards him, and the heavens that had opened for such a short time closed again.

And so he ordered the shoemaker to chisel the hair and the skin from Bhāī Tārū Jī‘s head, saying to him:

"You can see that I appreciate your wish. You shall not lose a single one of your precious hairs, for you shall relinquish them all in one."

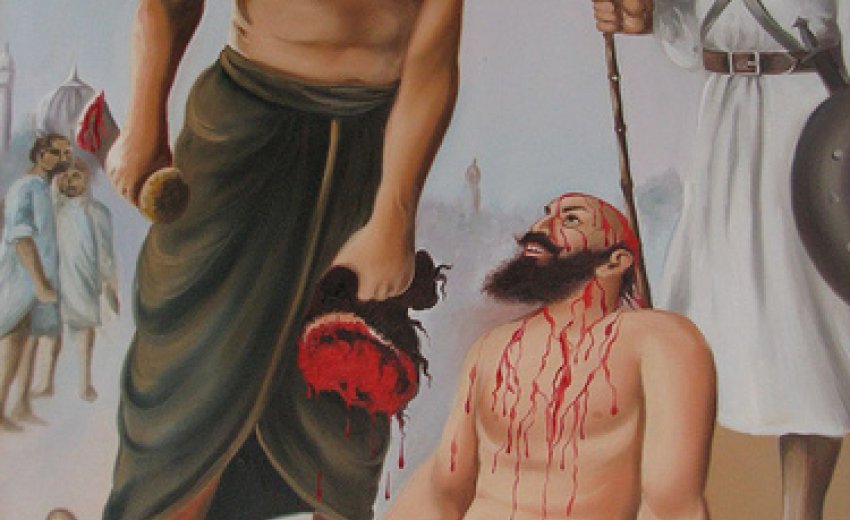

He waved his hand, and pitiless hands tied Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī with strong ropes and kept clasping him in an iron grip to keep him from resisting as the shoemaker began his gruesome task. This evil deed was committed on April 9, 1745.

But it is not that easy to separate the skin from the skull, and one has to be very callous to do such a thing. Bhāī Tārū Jī‘s heart started beating furiously with the pain, and his blood seeped from the ever-enlarging wound. Now and then his consciousness became dim and it seemed that to him that his soul and his body wanted to separate from one another, but time would not stand still for him and kept bringing him back to the brutal reality he was in. While he was conscious, he recited from the Gurbāṇī and chanted VĀHIGURŪ VĀHIGURŪ VĀHIGURŪ. Suddenly a terrible sensation of something being ripped apart ran through his body in incessant waves. The whole skin of his head had been pulled off. An open wound was exposed to the air like blazing poppy in the light of the setting sun, pulsing and pounding with pain, and pity asked love "Shall we release him for a moment?", and his consciousness faded away.

The Ḳhān remained unmoved even now and had the scalped Bhāī Tārū Singh thrown into the ditch around the prison, which was filled with refuse. Some compassionate prisoners hauled him out of the ditch and looked after him as best they could, but they could not really do much for him as they had nothing themselves.

Bhāī Tārū Singh Jīs soul had remained unscathed. His face betrayed traces of a great sadness. He reminded one of a lamp about to go out, but a glowing spark had remained, and this spark flickered VĀHIGURŪ JĪ.

Zakarīā Ḳhān, flush and satisfied with his bloody deed, retreated to his apartments to indulge in gluttony. After some time, he felt the need to urinate, but he couldn‘t. Try as he might, he could not pass a single drop. As the pressure on his bladder grew stronger and stronger, he sent for some doctors in despair. The physicians quickly realized that a bladder stone was blocking his urethra, and that there was nothing they could do to help him. As they knew what Zakarīā Ḳhān had done to Bhāī Tārū Singh they urgently advised him to ask his forgiveness, and Zakarīā Ḳhān, nearly insane with pain, really sent for Bhāī Tārū Singh and asked him to forgive him. But he also asked for his shoe, so that he could be beaten on the head with it. Bhāī Tārū Singh‘s prophetic words had become true.

Probably the blows on his head with the shoe made the bladder stone move slightly so that the Ḳhān was able to pass some water. But it was not enough. And so, after some days of maddening pain, this stone-hearted and cruel ruler, who had mercilessly tormented and tortured the Sikhs and others until death, died in his own filth.

A chronicle reports that Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī received the news of Zakarīā Ḳhān‘s death after about twenty-two days. He was too dedicated to GOD to feel even the slightest satisfaction when he was told. Shortly before Bhāī Tārū Singh Jī reached the twenty-fifth year of his life, he left the lands of the living and wandered to the fields from which there is no return.