This week marks the launch of the long awaited The Black Prince, the on-screen telling of the life of Maharaja Duleep Singh, the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, and his struggle with Queen Victoria’s rule. Interestingly, a second movie is being released later in the fall, Victoria and Abdul, which also centers around the relationship between Queen Victoria and a brown man.

Both movies are based on true stories and are set against the backdrop of the British rule of India. Victoria and Abdul, based on the book by Shrabani Basu, tells the story of a benevolent, misunderstood, lonely old woman who find comfort and companionship in a loyal servant from India. The Queen, played by Judi Dench, learns a new language, tries to eat a mango, and fights the patriarchal establishment around her. Littered with British humour, the trailer shows a light-hearted, funny, unlikely friendship between two people from opposite ends of the world; not unlike the dog and elephant videos we watch on the internet. Queen Victoria saves Abdul, the humble brown man, and decides she will take him on as a “project”. In an apparent reversal of power, Abdul becomes her teacher and the viewer is instructed to empathetically watch as this lonely woman finds purpose in life. The movie is completely void of the horrid violence of her rule that creates the circumstance of Abdul’s presence in the first place. The Queen declares herself the empress of India as an assertion of her right to Abdul. Her rule over India is nothing more than something that pushes the plot forward in this human-interest story.

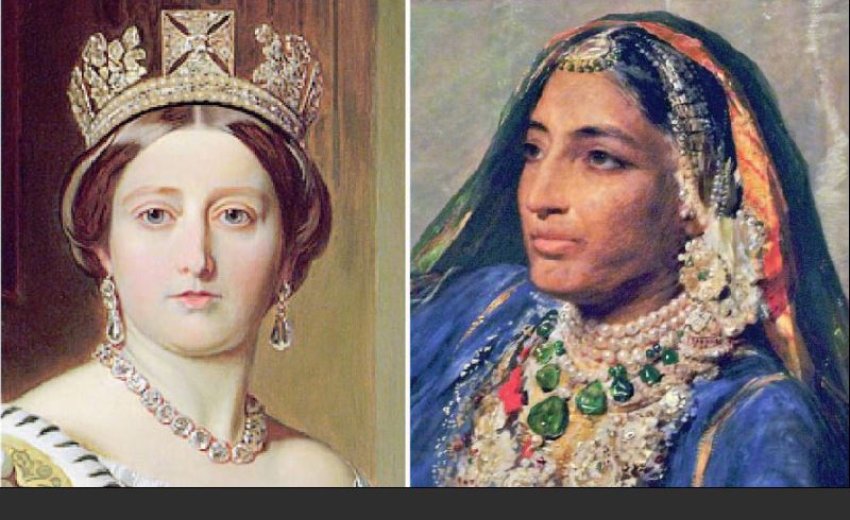

The Black Prince, on the other hand, is a stark departure from the British portrayal of Queen Victoria. In this movie, we see the British Empire from the perspective of Maharaj Duleep Singh, played by Satinder Sartaaj, after he is taken away from his mother, Maharani Jind Kaur, and exiled to England. He is raised as a Christian and we watch him struggle with his identity and his Empire over the course of his life. As a result of this movie being from a Sikh perspective, we have the rare chance of seeing a Sikh Maharani in a film. Maharani Jind Kaur, played by Shabana Azmi, directs the viewer’s perception of Queen Victoria. She shows the Queen as a woman who kidnapped her son, destroyed her empire, and hurt her people. We watch a powerful, yet ever so polite and passive-aggressive, clash of Queens on screen; the violence of Queen Victoria’s actions is in plain sight. Although we meet the Maharani in her later stages of life where her vision and health are failing, the fear she instills in the British and the complicated history of her rule is not diluted. She is not a love interest, a plot point, or a benevolent ruler; she is a rebel who struggles with her life, her consciousness, and the horrors she has seen.

The telling of Maharani Jind Kaur’s story, or the silence around it, has always been at the mercy of the men who surround her life. I recently had the opportunity to attend a screening in Brampton with the producers, actors, historians, and directors of The Black Prince. After the screening wrapped up, I listened as a well-intentioned, all-male panel made the progressive statement that Sikh women’s stories need to be given voice; the irony was lost on them. But essentially, having the story of a Sikh woman on screen is still a bold and progressive act.

On her worst days, Queen Victoria does not struggle with representation. She has had multiple, full length, feature films made about various aspects of her life (The Young Victoria, Mrs. Brown, Victoria and Albert, Victoria the Great) and has been a secondary character in even more. There is a well-balanced, multifaceted understanding of many aspects of her being, all in a positive light.

How we tell stories is powerful; storytelling possesses the ability to reproduce the power of history or resist it. As we watch these two stories with Queen Victoria and her relationship with a brown man, we also watch the modern-day strength of her legacy. Victoria and Abdul will most likely be more successful; the neocolonialism of the film industry is no secret. Here then, is a small chance to reverse some of the original tragedy of the life of Maharani Jind Kaur. We have a moment where two movies are being released. You, the viewer, get to decide where you put your money and whose perspective gets priority. The stories of two powerful women will be told but you get to choose whose story you listen to.

By Dr. Jaspreet Kaur Bal

Dr. Jaspreet Kaur BalDr. Jaspreet Kaur Bal is a Professor in the Child and Youth Care program at Humber College in Toronto. She completed her PhD in Cultural Studies from Queen’s University in Kingston Ontario, where she focused on children’s rights, education, and returned for fieldwork to her village in Punjab. Bal serves on the Board of Directors of the Sikh Feminist Research Institute and Kaurs United International.