Let me overwhelm you with some factoids, then we’ll try moving forward.

Young and brash, I came to this country a generation ago. Then I could count on the fingers of one hand the number of recognizable Sikhs on the streets of a city the size of New York and often pined for a familiar face in a sea of strangers. When curious non-Sikhs asked if we had a place of worship (gurduara) nearby, my ironical response said it all: “Yes we do but they are about 3000 miles away in California and in Vancouver, Canada.”

The years have turned my world upside down.

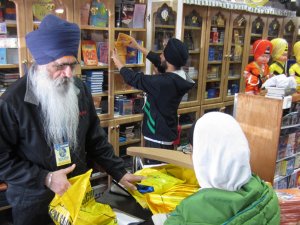

Now almost 20 gurduaras are within commuting range of where I live, and perhaps twice as many if you count the whole state of New York. About 250 gurduaras dot the landscape of United States of America. Surely, a matter of rejoicing and satisfaction… but for one caveat.

With the exception of a few that I know about, many of our gurduaras have accumulated a horrible track record unbecoming a place of worship. The list is a long one: Dishonest or non-existent electoral procedures, unresponsive authoritarian management, absence of transparency, accountability and self-governance while flouting the norms of common sense or even their own Constitutional framework. Violent interactions among attendees and management followed by legal recourse are not uncommon sequelae. Should such shenanigans be the markers of a spiritual path exemplified by love and service to humanity without discrimination of caste, color or gender that normally fuel disagreements in public space? Today I present my gut reaction to this paradox.

If a whole community spread over as vast a land as the United States exhibits common symptomology then there must be a common etiology. Many gurduaras are beset by these problems and have been rendered largely dysfunctional by them. It is true that some gurduaras serve economically challenged neighborhoods with marginally educated congregants existing in dire economic straits. Yet, a similar picture of fragmented gurduara management emerges whether one is looking at impoverished communities or at posh neighborhoods and historic towns where Sikhs drive luxury cars and own palatial homes, and where the gurduara buildings are historic landmarks with local political bigwigs residing nearby. Not an iota of difference exists between the two extremes in the viciousness of the disputes which are surely not the fault of any one person, no matter how vile.

To my baffled, simple mind the thought came that if the large American Sikh community is behaving thus, two possible explanations remain: First, that a fundamental flaw in Sikh teaching has surfaced in the diaspora Sikhs of North America. A careful reading of history, traditions and teachings of Sikhi quickly rubbished that notion. The equally unacceptable alternative is that perhaps a new, highly contagious virus caught up with us after a few hundred years of latency, and now the infection may have affected the whole body politic of the Sikh nation.

Such examples surface every day; just watch the latest unfolding news on public health. Newer bugs enter us, infecting all systems quietly with unimagined speed and unheard-of urgency, overriding all control systems, even penetrating a people’s DNA, particularly if it is a largely isolated population. Microbe hunters, cell biologists and geneticists tell us that such viruses take control of organelles, cells and systems that are vital for function and survival. Now the community seems to have caught it — almost a gene mutation for madness. Do we now have an epidemic on our hands? Mind you, Sikhs are not a genetically isolated people.

After this somewhat fanciful musing only two therapeutic choices appeared hopeful: Either large scale mandated mass counseling services for every Sikh man and woman, as if they have all gone nuts, or looking to modern interventional cellular and subcellular gene therapy emerging techniques to put us back on track.

After some obsessing, a sensible alternative response surfaced, and so I counsel patience. Let us not leap to egregious and hasty judgements.

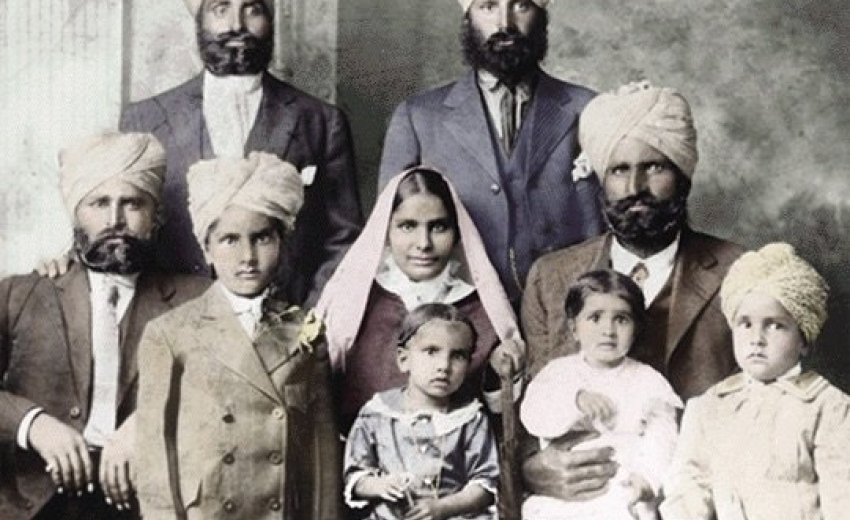

Most Sikhs are immigrants in this country. Prior to dramatic shifts in the 1960’s, immigration policy was radically biased against Asians, and there were a small number of Sikhs in the U.S.A. Laws changed and a flood of Indians came. Sikhs, mostly from Punjab, in the northwest territory of India, enjoy an enviable reputation as warriors dedicated to honest work ethic; they earned for Punjab coveted recognition as the nation’s bread basket that freed India of its yearly famines. Sikhs are also the backbone of India’s muscle – its coveted armed forces. Sikhs are a vigorous, prominent minority of barely two percent in Hindu India and even a smaller statistical presence in contemporary America, or any other part of the world.

Quite expectedly, then, Sikh migrants to America are a mix of students, technocrats, and business professionals but often are from agrarian farming roots. Some problems of language and culture challenge them, as for most migrants from anywhere.

These first Sikh migrants founded the 200 odd Gurduaras in the United States that primarily cater to the needs – religious, cultural, linguistic etc., also in music cuisine and ambience –of the Punjabi people and their nostalgia for a home (Punjab) that they had abandoned. The gurduara, by definition the community center of a people, becomes critical in re-creating the aura and ambiance of Punjab by capturing the essence, sights, smells and sounds of the home they left behind.

But for their progeny, born and brought up in the new country, the home is different as are the sights, sounds and smells. And there lies a disconnect.

Now, despite the fact that a large majority of our gurduaras are beset by problems that have rendered them largely dysfunctional, some hopeful progressive examples are arising here and there, especially as the younger generations take over.

A migrant’s heart and soul often long for the home he has abandoned even while he feverishly works to construct a new home in a new land. Remember that a house is erected in days or months, making a house into a home takes a lifetime. Identity and loyalty remain split a while; that’s an immigrant’s reality though not always in his awareness. To each phase there is a season with an ebb and flow. These are not to be condemned but valued and deserving respectful patience. In that lies a defining hurdle. The Indian cultural milieu, perhaps because of its pervasively defining caste and past colonial realities, comes with an overwhelming vertical structure, crudely but aptly labeled as the Master/Servant; King/Subject or Kick down/Kiss up paradigm. I hasten to add that Sikhi rejects this baggage entirely but its reality prevails.

Migrants bring cultural practices and attitudes best tagged as habits of the heart. They prevail despite the best teachings of great religions that speak of egalitarian societies, self-governance, gender equality and, freedom of expression with accountability. The result is a mélange of good teaching and bad practice that coexist.

When a leader ascends the ladder of success in the primarily patrilineal Indian system his sense of self is defined more by ancient cultural commandments of Indian life and less by values of common good. He becomes the leader but sees himself as the king. To him the king is the law, not that the law is king. Therein lies the defining difference between the culture that shaped us and the reality in which we live today. Yet, when he goes to work in an office or business that runs by western values he functions as a loyal servant of the new order where he is the migrant and follows the laws, regulations and practices he should. When he comes home to family or gurduara he often reverts to the ways of his home that his body may have truly left, but not his mind.

Perhaps because of the closed-shop mentality of many gurduaras and the never-ending turmoil, congregations often become overwhelmingly uninvolved. When asked they rarely offer honest opinions until the pot boils over into visible conflict. Perhaps the allure of apathy reflects the fervent desire for peace. We need some psychic respite after all the commotion in gurduaras pretty worldwide post 1984. Matters lie dormant today but perhaps as a volcano waiting to explode. Remember that Sikhs and Sikhi present, since their beginnings, a glorious history of dynamic activism, not fear.

More than just cessation of hostilities, peace is a state of mind. To quote the comic strip Pogo, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” We may have peace now, but at what price? I am reminded of the Latin aphorism ignoti nulla cupido meaning that one does not desire what one does not know.

Yet, it is almost as if a highly contagious virus has caught up with us or that an epidemic of madness has hit us.

My reasoning though plausible remains hypothetical. So, where lies the critically needed therapy? I suggest that we open that box another day.

Our existing conflicts are both inter and intra generational; they lie at the core of our community’s dysfunctional reality and our gurduara imbroglio. (Generational conflicts are not uncommon in other religions as well!) Mind you, I am not prescribing gene-therapy or counseling en masse. Just some self-reflection might be all that the doctor ordered

My intention here is less a sermon or scolding and more Cri du Coeur. I close with a bit of American folk wisdom: Ask me no questions and I’ll tell you no lies.