Over 100 Years in the Pacific Northwest

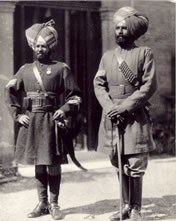

Sikh soldiers from the British Empire traveled the globe. Their stories of opportunity inspired other Sikhs to venture to foreign lands.

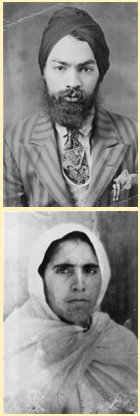

Pictured here are two members of the 1st Punjab Cavalry in 1893. Photograph credit: Courtesy of |

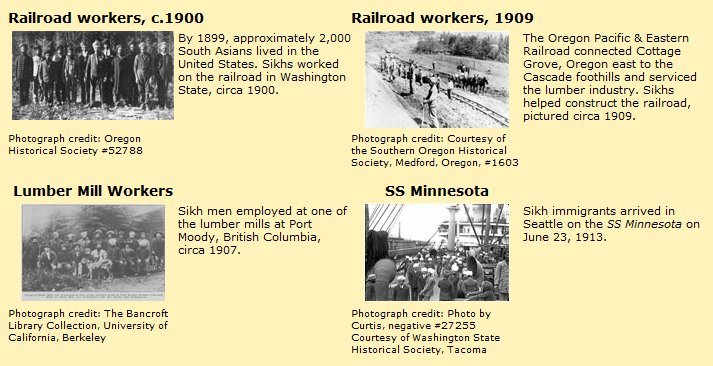

Like other groups in the Pacific Northwest, the story of the Sikh community stretches back to pioneer days of our region, where lumber, farming and fishing dominated the economy and railroad tracks were still being laid to connect us with the rest of the continent. The first well-known record of Sikhs visiting the Pacific Northwest was in 1897 when Hong Kong-based Sikh soldiers from the British Empire traveled through Canada on the way home from Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in London. They saw the potential to settle and work in North America, and shared their vision with other Sikhs back home in Punjab. Soon, Sikh immigrants – mostly male laborers – entered North America through West Coast ports, including San Francisco, Astoria, Seattle and Vancouver. At first, immigration began without incident, but soon, because of prejudice and racism, Sikhs, like Chinese and Japanese immigrants before them, encountered outright hostility. Citywide riots in Vancouver, British Columbia and Bellingham, Washington forced Sikh laborers from their homes. For many years, Sikh immigrants struggled to build a community in the Pacific Northwest despite laws prohibiting them from owning land. Additional laws barred women from joining their husbands and eventually banned immigration all together. Amidst calls in India for independence from British rule in the 1910s, many overseas Sikhs returned to Punjab to aid in the movement to free India. Denied rights in North America, they returned to South Asia where they could fight for freedom. Although the entire Sikh community did not depart, this event, combined with restrictive immigration laws, resulted in dwindling numbers of Sikhs in the Pacific Northwest. The Sikh community did not begin to grow again until the end of World War II with the return to normalcy of travel and changes in immigration laws allowing for small quotas of Sikhs to come to Canada and the United States. In the 1960s, both nations reformed laws again, removing discriminatory policies and allowing substantially increased immigration by Sikhs from South Asia. Tragically, the next large wave of Sikh immigration would begin in 1984. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to attack the Harmander Sahib in Amritsar as part of Operation Blue Star. This attack was part of a mass-scale oppression of Sikhs by the Indian government. The Sikhs were fighting for basic rights denied in the Indian constitution. The government accused Sikhs of separatism and as a result of this attack, thousands of innocent devotees were martyred. Historic and sacred institutions, including the Sikh Reference Library, which housed priceless manuscripts, letters written by the Gurus, handwritten copies of Guru Granth Sahib Ji and historical records, were burned. Two Sikhs assassinated Indira Gandhi to avenge the killing of innocent Sikhs in Amritsar. Over the next three days, approximately 10,000 to 15,000 Sikhs were brutally murdered in anti-Sikh pogroms, encouraged and directed by state police forces, the civil administrations and the leaders of the ruling Congress party. What followed was over a decade of State oppression against the Sikhs, which included extra-judicial killings, disappearances, illegal cremations, torture and rape by Indian police and government agencies. Fearing for their lives, many Sikhs immigrated to North America in hopes of starting a new life. Today, the Sikh community in the Pacific Northwest continues to grow, with new arrivals coming to work and raise families. Many younger members of the community are now second, third and fourth generation Sikhs born here in the Pacific Northwest, who know of Punjab only from brief vacations or stories told by their grandparents and parents. |

| |

Anti-Hindu Riots Landing in Canada at the CPR pier  SS Komagata Maru, Vancouver, British Columbia  Oregon  Bhagat Singh Thind  Harbhajan Singh Khalsa Yogiji  Rattan Singh & Gurnam Kaur  Smithsonian Institution Exhibition  |

On September 4, 1907, a mob of approximately 500 men attacked Sikhs living in Bellingham, Washington, forcefully removing them from the town. Known as the “Anti-Hindu Riots,” the attack began with stones thrown at two Sikh workers on C Street, the center of the Sikh community. Although the initial instigators were arrested, the violence quickly escalated, resulting in smashed windows and doors and mobs encircling and threatening the Sikhs living there. Overpowering the small police force, the mob forced the community to either leave immediately or find refuge in the basement of city hall for the night. The next day approximately 300 Sikhs left the town. Sikh immigrants usually traveled by steamship from Calcutta to Hong Kong, then from Hong Kong to Canada or the United States, a total journey of 30 days. An immigrant from India to Canada was required to have $200 in possession versus those from Europe who only needed $25. It is estimated that 2,623 South Asians entered Canada in 1907 – the final year before immigration was curtailed severely with only six admitted in 1908 and a total of 29 admitted over the next five years. Here, newly-arriving Sikhs loaded their belongings onto horse-drawn wagons at the Canadian Pacific Railroad pier in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1907. Photograph credit: Vancouver Public Library #9426 In 1908, the Canadian government – eager to keep South Asians from immigrating and settling in Canada – suggested that they should voluntarily leave and settle in another British colony, in this case, British Honduras. In fall of 1908, they sent a delegation, including representatives of the Sikh community, to British Honduras. Upon their return, members of the Sikh community gathered at the Vancouver Gurdwara and unanimously resolved to refuse to go. Although the government dropped this tactic by the end of the year, that same year they also attempted to stop Sikh immigration by passing a “Continuous Voyage Order” – requiring prospective immigrants to travel in an uninterrupted journey, and since no such voyage existed from South Asia, creating a requirement for immigration that would be impossible for Sikhs to meet. In 1914, however, 376 Sikhs, led by Bhai Gurdit Singh, challenged this order by making the trip on the vessel, Komagata Maru. Arriving in Vancouver on May 23, 1914, they were refused entry and kept anchored in Vancouver harbor for two months. Correspondence from this time indicates the conditions were inhospitable, with lack of food, water and medical care. On July 23, 1914, they were escorted out of Canadian waters by naval guard, sent on the long journey back to South Asia. Upon return, the ship and its passengers were regarded as threats by the British colonial government – viewed as members of the Ghadar Party seeking freedom for South Asia from colonial rule – and subsequently arrested or killed. The passenger lists, reproduced nearby, contain the names of these brave individuals who took a stance and made great sacrifices for freedom on both sides of the world. Photograph credit: View of crowded conditions on the Komagata Maru, Vancouver Public Library #6232 From 1906 to 1922, Astoria, Oregon had a “Hindu Alley,” a block of bunkhouses, including a central cookhouse, near the Hammond Mill, which employed nearly 100 laborers from South Asia. Old-time Astorians reported that “they all wore white turbans,” and were therefore most likely Sikhs.

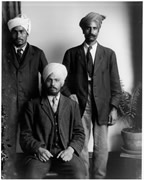

After the case, Thind remained in the U.S. and went to on to receive his PhD from the University of California, Berkeley. He then began a lifetime of work in the field of metaphysics where he drew on many concepts from Sikhism, giving lectures and writing several books. Photograph credit: Courtesy of The Sikh Coalition

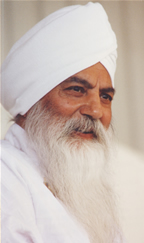

Photograph credit: Courtesy of Ek Ong Kaar Kaur Khalsa

1926 Canadian Pacific Steamship Line ticket for Rattan Singh from Hong Kong to Vancouver 1943 Receipt for money wired to Gurnam Kaur from New Westminster, British Columbia to Amritsar, Punjab 1950 Letter sent from Gurnam Kaur to Canada’s Department of National Health and Welfare Application for Search of Census Records for Rattan Singh Photograph credit: Courtesy of Mike Ghuman

Photograph credit: Courtesy of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution |